I traveled across Uzbekistan to research a biography of Tamerlane, the 14th-century Tatar conqueror known locally as Amir Temur. I hadn't expected to see so many pictures of him. He stared at you wherever you went, from newspaper mastheads to highest-denomination banknotes. A magnificent statue of him on horseback dominated a square that bore his name in the heart of Tashkent.

The clue to his re-emergence from decades of Soviet-sanctioned vilification came on a series of street hoardings portraying Tamerlane and President Islam Karimov together. Styled in the Soviet era as a murderous barbarian -- he cut a swath through Asia, celebrating his victories by building towers from the severed heads of his enemies -- Tamerlane had become the hero of the newly sovereign Uzbekistan.

"It is well known that this dignified and just ruler always dealt with the world with good and kind intentions," proclaimed Khalq Sozi, the official organ of Karimov's People's Democratic party. "And our independent republic, from its very first steps, has announced the very same goals: to conduct itself in the world with kindness and goodwill."

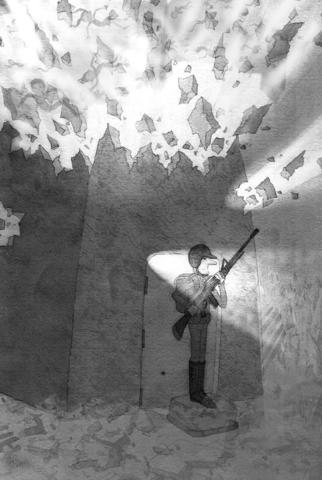

ILLUSTRATION: YUSHA

Contemporary sources report Tamerlane's execution of 100,000 prisoners in cold blood shortly before his storming of Delhi in 1398. On taking Baghdad in 1401, he erected 120 towers containing 90,000 skulls. The parallel, then, is not entirely absurd: Tamerlane and Karimov are both butchers, only the Tatar's depredations were on a global, rather than a domestic scale.

In Uzbekistan I found a wildly romantic country of desert, steppe and mountain, with stretching landscapes and architectural treasures of Bukhara, Samarkand and Khiva that simmered in the imagination. But it was a beleaguered place, its people downtrodden, its strutting security forces bent on following and, if possible, obstructing your every move. If the police wanted to go though your suitcase every day, there wasn't much you could do about it (Uzbeks call their capital "Tashment," ment being the slang for cop). Local translators risked night-time visits from state-paid thugs in uniform. Who had the foreigner been talking to and why? What was he doing in Uzbekistan? Punch. Slap. Threats.

One evening in the world before Sept. 11, I drank whisky with a senior diplomat at the British embassy. Even then, security around the building was very tight. After interminable checkpoints and identity checks I was ushered into an elegantly furnished residence, a little corner of the UK complete with portrait of Her Majesty, Oriental rugs and a decent library.

The conversation moved swiftly from Tamerlane to politics. Given Karimov's already well-known abuses of human rights and suppression of opposition, I was taken aback by the British line on the regime (government seems too decent a word for it). One had to understand that Karimov had grown up and risen to power under the USSR, when standards were rather different. He wasn't an evil or nasty man; the country was in transition; the UK needed to engage this small nation emerging from the Soviet yoke. The tune I heard at the embassy rang oddly with the ethical foreign policy proclaimed by Robin Cook, the then UK foreign secretary.

Since that time Washington and London have moved far beyond engagement to a close alliance with Karimov's regime, attributing the shift to the changed strategic realities of the post-9/11 world.

Natural gas helps, too. Yet this is a regime whose suppression of its own people precisely provides fertile soil for Islamist terrorist recruitment. Such cause and effect are illustrated in the Ferghana Valley, home to the violence of recent days after a peaceful protest boiled over to a prison break, and Uzbek security forces shot down innocent men, women and children in the streets.

Ask the award-winning poet and dissident writer Mamadali Mahmudov what he makes of Karimov's mantra Rasti Rusti (Strength in Justice), borrowed from Tamerlane. Ask him too what the inside of an Uzbek prison looks like. Mahmudov was arrested on Feb. 19, 1999, three days after a series of bomb explosions aimed at Karimov rocked Tashkent. He was charged with threatening the president and the constitutional order and sentenced to 14 years in prison. His chief crime appears to have been links to the Erk opposition party, outlawed by the government since 1993.

The following excerpts are taken from his testimony smuggled out of court in 2000: "They put a mask on me and [kept me] handcuffed ... My hands and legs were burned. My nails turned black and fell off. I was hung for hours with my hands tied behind my back. I was given some kind of injection and I was forced to take some kind of syrup ... In wet clothing, in my icy prison cell, I spent the days and nights all alone in unbearable suffering ... They told me they were holding my wife and daughters and threatened to rape them in front of my eyes."

The UN's words for torture in Uzbekistan are "widespread and systemic." Mahmudov remains in jail; in 2003, he was moved to Chirchik prison, where the conditions are said to be less harsh.

If Karimov now faces a serious challenge from domestic Islamists -- and it is not at all clear that he does, because all dissidents and opposition groups are routinely labeled as Islamic fundamentalists -- he has only himself to blame. The mosque in Uzbekistan has become a refuge from the regime. A small number may be terrorists, among them members of the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan. The majority are not.

In the ancient city of Bukhara, I found rampant regime paranoia about the Islamic threat. Known as the "Dome of Islam" in Tamerlane's time, Bukhara has a distinguished pedigree in the field of Islamic teaching, yet the minarets are strangely silent.

When I asked the imam of the great Kalon Mosque, an affable man with a snowy beard, why the muezzins were not broadcasting the call to prayer, he looked uncomfortable. He was appointed by the state and his sermons were monitored. There were a number of different religious minorities in the city, he explained, and no one wanted to disturb them in the night. During travels in a dozen or so Muslim countries, I have never encountered such solicitude for the beauty sleep of the unbelievers.

In the northwestern town of Muynak, victim of the Aral Sea environmental catastrophe, toxic winds unleashed chemicals across the town. The people looked shockingly sick. A fish-canning factory resembling a medieval dungeon paid its workers in melons.

In tears, the owner of my hotel, a single mother, said she didn't have enough money to feed her newborn baby and pay for the electricity. In the midst of this misery, the mayor, a fat venal man with a penchant for expensive suits, was laying an elaborate Tarmac drive to his mansion.

"Don't listen to the people," he replied furiously when I relayed complaints from the streets.

At all corners of the country, people expressed their desperation. Muzafar, a young man from Tamerlane's birthplace of Shakhrisabz far to the south, in the outskirts of Samarkand, pleaded: "You must help me leave ... we cannot go on like this." Now he lives in New York.

Murad, who gallantly fielded masses of research requests from me, spoke of his repeated beatings by police. His crime? He is homosexual.

Scroll through the comments on the BBC's Web site posted by Uzbeks unable to express their opposition to Karimov any other way. Some use pseudonyms for their own security.

"Governments who are still allies and support Karimov's repressive regime should be condemned," writes Abdullah from Samarkand. "This guy [Karimov] is going to end up dead some day in a very unpleasant manner," warns Kunchilik Uzbakov.

A journalist who watched Karimov at his press conference in Tashkent after the Andizhan killings told me: "He doesn't even blink when he tells the most outrageous lies ... When Karimov asked rhetorically: `Do you see any disturbances on the streets of Tashkent?' I wanted to shout out, `No, because it's a police state and everyone lives in terror of you. You are the biggest terrorist in all Uzbekistan!'"

Justin Marozzi is the author of Tamerlane: Sword of Islam, Conqueror of the World, published in paperback later this year by HarperCollins.

Speaking at the Copenhagen Democracy Summit on May 13, former president Tsai Ing-wen (蔡英文) said that democracies must remain united and that “Taiwan’s security is essential to regional stability and to defending democratic values amid mounting authoritarianism.” Earlier that day, Tsai had met with a group of Danish parliamentarians led by Danish Parliament Speaker Pia Kjaersgaard, who has visited Taiwan many times, most recently in November last year, when she met with President William Lai (賴清德) at the Presidential Office. Kjaersgaard had told Lai: “I can assure you that ... you can count on us. You can count on our support

Denmark has consistently defended Greenland in light of US President Donald Trump’s interests and has provided unwavering support to Ukraine during its war with Russia. Denmark can be proud of its clear support for peoples’ democratic right to determine their own future. However, this democratic ideal completely falls apart when it comes to Taiwan — and it raises important questions about Denmark’s commitment to supporting democracies. Taiwan lives under daily military threats from China, which seeks to take over Taiwan, by force if necessary — an annexation that only a very small minority in Taiwan supports. Denmark has given China a

Many local news media over the past week have reported on Internet personality Holger Chen’s (陳之漢) first visit to China between Tuesday last week and yesterday, as remarks he made during a live stream have sparked wide discussions and strong criticism across the Taiwan Strait. Chen, better known as Kuan Chang (館長), is a former gang member turned fitness celebrity and businessman. He is known for his live streams, which are full of foul-mouthed and hypermasculine commentary. He had previously spoken out against the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and criticized Taiwanese who “enjoy the freedom in Taiwan, but want China’s money”

A high-school student surnamed Yang (楊) gained admissions to several prestigious medical schools recently. However, when Yang shared his “learning portfolio” on social media, he was caught exaggerating and even falsifying content, and his admissions were revoked. Now he has to take the “advanced subjects test” scheduled for next month. With his outstanding performance in the general scholastic ability test (GSAT), Yang successfully gained admissions to five prestigious medical schools. However, his university dreams have now been frustrated by the “flaws” in his learning portfolio. This is a wake-up call not only for students, but also teachers. Yang did make a big