The debate is so old it should have its own place in the Shakespearean canon. Is Shylock, the Jewish moneylender who demands a "pound of flesh" from a debtor, a villain or a victim? Every time The Merchant of Venice is staged, the debate is restaged along with it. Does Shakespeare's play merely depict anti-semitism, or does it reek of it? Is the Bard describing, even condemning, the prevalent anti-Jewish attitudes of his time -- or gleefully giving them an outlet? The papers of a million students are marked forever with such questions.

Yet now they have a new force. Because the Merchant is playing in a new medium, making its debut as a full-length, big-budget feature film -- complete with a top-drawer Hollywood star, Al Pacino, in the de facto lead.

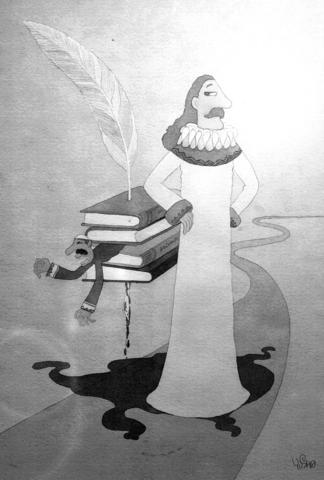

YUSHA

The film declares its own inten-tions early. The pre-credit sequence, complete with Star Wars-style scrolling text, seeks to contextualize. The opening image is of a crucifix, rapidly juxtaposed with the sight of Hebrew texts put to the flame. The words on the screen tell us that "intolerance of the Jews was a fact of 16th-century life." To prove it we see a mini-pogrom, with a Jew hurled from the Rialto Bridge.

It's clear that director Michael Radford does not want to make an anti-semitic film. But he has big two problems. The first is the play. The second is the medium.

Start with the play. We may want it to be a handy, high-school-friendly text exposing the horrors of racism, but Shakespeare refuses to play along. As the great critic Harold Bloom has declared, "One would have to be blind, deaf and dumb not to recognize that Shakespeare's grand, equivocal comedy The Merchant of Venice is nevertheless a profoundly anti-semitic work."

There is no getting away from it: Shylock is the villain, bent on disproportionate vengeance. Crucially, his villainy is not shown as a quirk of his own, individual personality, but is rooted overtly in his Jewishness.

Thus, he is shown as obsessed by money, a man who dreams of moneybags, whose very opening words are "three thousand ducats."

When his daughter betrays him and flees with a Christian lover, it is her theft of his money which is said to trouble him as much as the loss of a child. "As the dog Jew did utter in the streets/`My daughter! O my ducats! O my daughter!'"

Since the laws that barred Jews from almost all activity besides finance had led to the stereotype of the avaricious Jew, Shakespeare is dealing here not with a specific trait of Shylock the man but an anti-semitic caricature.

So it is with his demand for revenge, playing on the ancient notion of the Jews as a vengeful people ("An eye for an eye... ").

The same is true of the very forfeit Shylock demands from Antonio. A Jew seeking Christian flesh is surely meant to stir memories of the perennial anti-semitic charge, known as the blood libel, that Jews use Christian blood for religious ritual. Above all, it evokes the accusation that fuelled two millennia of European anti-semitism -- that the Jews killed Christ.

Radford can dress his film up as prettily as he likes -- and the costumes, Rembrandt lighting and Venetian locations certainly ensure that his Merchant is lovely to look at. But he can't dodge this hard, stubborn fact. Shylock's villainy is depicted as a specifically Jewish villainy. "And by our holy Sabbath have I sworn/To have the due and forfeit of my bond." Macbeth's murderousness is not a Scottish trait, nor is Hamlet's indecision a Danish one. But Shylock's wickedness is Jewish.

Doubtless, like the play's other defenders, Radford would cite the bad behavior of the Christian characters and Shylock's legendary, humanizing "Hath not a Jew eyes... " speech. But these defenses don't really work.

If Antonio, Bassanio and the rest act badly, the play's assumption is that they have failed fully to honor their fine and noble faith, Christianity. They are being bad Christians. When Shylock acts badly, Shakespeare suggests he is fully in accordance with Jewish tradition. Shylock plots Antonio's downfall with his friend Tubal, promising to continue their dark talk "at our synagogue."

As for Shylock's renowned apologia, it brings only little sympathy. For it turns out to be an "over-clever" defense by Shylock of his own bloodlust -- an argument that, since Jews are the same as Christians, he is entitled to exact the same revenge they would.

So the film-maker has a problem with the play he has chosen. But -- and this may be the bigger surprise -- he has deepened his trouble by making a film.

For the very nature of the medium aggravates the traditional dilemmas of staging The Merchant of Venice. We may want to dismiss Portia and friends as ghastly airheads, in contrast with weighty Shylock, but that's tricky when they are played by beautiful A-list film stars, in gorgeous locations accompanied by delightful music. How can we do anything but sympathize with Antonio, when he's played by Jeremy Irons -- exposing his chest to Shyock's knife in an almost Christlike pose?

Film is an emotive medium, uniquely able to manipulate through lighting and music as well as words. Shylock's daughter lives in a dank, dark hellhole when she is still a Jew; once she betrays Shylock and converts to Christianity, she is shown in the flush of youthful love and only in the most sumptuous of locations. Even if she gives the odd rueful stare into middle distance, hinting at loss, the visual language of the film is that joy, laughter and sex live on the Christian side of the ghetto wall. Among the Jews there is only brooding sorrow and malice.

More importantly, Shakespeare is simply experienced differently on stage. Even when it's not at the Globe theatre, we understand when we see a Shakespeare play that we are seeing a historical artifact, written several centuries ago. Instantly that provides some context: these were the attitudes of the time. That sense is diminished in the most modern of forums, the cinema. To hear the words "dog Jew" shouted on Dolby Surround speakers; to see a Jew fall to his knees and forced to convert to Christianity on a wide screen, cannot fail to have a different, and greater power.

That doesn't mean that such scenes should never be shown on film. On the contrary, there should be films that take on anti-semitism. But Michael Radford is not in that game. Amazingly, last week he told the London-based Jewish Chronicle, "I was never worried about the anti-semitism of the play."

Many, though not all, of the critics have shared his insouciance. I suspect this is because they believe modern audiences have been so sensitized by the Holocaust that they are all but inoculated against anti-semitism. The result is that stories of anti-Jewish hatred take on an almost allegorical quality -- as if they are not about Jews at all, but are, instead, parables for racism or intolerance in general. (Radford has hinted that his film should be understood in the light of the current collision between Islam and the West.)

This might work if Shylock was, say, an Inca, or a Minoan -- if, in other words, the Jews were no longer around. But Jews are still around -- and so, unfortunately, is anti-semitism.

Yesterday’s recall and referendum votes garnered mixed results for the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT). All seven of the KMT lawmakers up for a recall survived the vote, and by a convincing margin of, on average, 35 percent agreeing versus 65 percent disagreeing. However, the referendum sponsored by the KMT and the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) on restarting the operation of the Ma-anshan Nuclear Power Plant in Pingtung County failed. Despite three times more “yes” votes than “no,” voter turnout fell short of the threshold. The nation needs energy stability, especially with the complex international security situation and significant challenges regarding

Most countries are commemorating the 80th anniversary of the end of World War II with condemnations of militarism and imperialism, and commemoration of the global catastrophe wrought by the war. On the other hand, China is to hold a military parade. According to China’s state-run Xinhua news agency, Beijing is conducting the military parade in Tiananmen Square on Sept. 3 to “mark the 80th anniversary of the end of World War II and the victory of the Chinese People’s War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression.” However, during World War II, the People’s Republic of China (PRC) had not yet been established. It

There is an old saying that if there is blood in the water, the sharks will come. In Taiwan’s case, that shark is China, circling, waiting for any sign of weakness to strike. Many thought the failed recall effort was that blood in the water, a signal for Beijing to press harder, but Taiwan’s democracy has just proven that China is mistaken. The recent recall campaign against 24 Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) legislators, many with openly pro-Beijing leanings, failed at the ballot box. While the challenge targeted opposition lawmakers rather than President William Lai (賴清德) himself, it became an indirect

A recent critique of former British prime minister Boris Johnson’s speech in Taiwan (“Invite ‘will-bes,’ not has-beens,” by Sasha B. Chhabra, Aug. 12, page 8) seriously misinterpreted his remarks, twisting them to fit a preconceived narrative. As a Taiwanese who witnessed his political rise and fall firsthand while living in the UK and was present for his speech in Taipei, I have a unique vantage point from which to say I think the critiques of his visit deliberately misinterpreted his words. By dwelling on his personal controversies, they obscured the real substance of his message. A clarification is needed to