August is a strange month. Supposedly, the financial markets are in a state of torpor, but in recent years that has not always been the case. Weird stuff happens, be it Saddam's invasion of Kuwait, the attempted coup against Gorbachev or the Russian debt default. This year the story is oil.

Over the past few weeks,

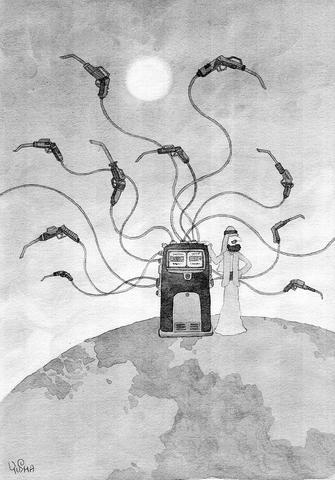

YUSHA

the price of oil on the futures exchanges has crept up and up, and on Friday night it was nudging US$45 a barrel. The expectation is that it may go higher.

"Fifty, sixty dollars a barrel is thinkable for the first time since 1979 ... But so much has changed between then and now that prices might have to go even higher before demand growth slows down," said Deborah White, senior economist at SG Commodities in Paris.

There is no single explanation for why oil is currently so expensive. Strong global demand is certainly an important factor, with China's explosive growth rates putting pressure on the capacity

of oil producers. There is enough crude to go round, but only just. The lack of wiggle room means any threatened disruption to the flow of oil has a rapid impact on prices, so it's not difficult to see why the shenanigans at Yukos have made oil dealers jittery. The Russian company accounts for around 1.6 million barrels per day -- 2 percent of global daily output -- which is similar to the increase in production that OPEC promised at the start of June.

These are the circumstances in which speculators flourish. Hedge funds attract high-rolling investors by promising to make them

hefty returns on their funds, but

that requires volatility. In recent months, little has been happening to stocks, bonds or currencies, so the hedge funds have been piling into the one market that has seen some action -- oil.

But speculation cannot explain everything. Some oil analysts believe that this upward move is different from those in the past. Then the price tended to spike as a result of a shock; this time the rise has been steadier, suggesting that the rise is based more on market fundamentals rather than on war, an embargo or any other form of supply disruption. On the gloomiest scenario, we are getting an early taste of life as the oil wells run dry, which means that while the price may jag around, the long-term trend will be up.

Stephen Lewis, one of London's most thoughtful analysts, puts it this way: "The kind of economic growth rates to which policymakers in the oil-consuming countries are committed appear to be generating growth in the demand for oil well above the underlying rate of growth of supply. Higher prices should certainly act as a spur to the development of exploitable oil resources, but it is not at all evident where the large oil fields will be found to replace supplies from the US, the Middle East and the North Sea, which all appear to be past their production peaks."

Lewis draws the obvious conclusions from this analysis: firstly, the West should be embarking

on a serious rather than cosmetic attempt at energy conservation; secondly, those who hold out the prospect of a glittering medium-term future for the global economy are perhaps not in full possession of the facts.

Actually, the short-term prospects don't look too clever either. In the UK, this could be as good at it gets for growth, with the likelihood that a combination

of more expensive money and energy eats into household incomes and corporate profitability over the coming months. In the US, the squeeze on real incomes caused by higher gas prices is already starting to have an impact on consumer spending.

As Andrew Oswald, economics professor at Warwick University, has pointed out, each of the peaks in oil prices since the early 70s has been associated with recession in the West. There is, as Oswald has shown, a strong link between oil prices and US unemployment, and despite what some optimists say, the world is still heavily dependent on the black stuff.

"People say oil is no longer important, but we are now using over 80m barrels a day of the

stuff for the first time. The world economy still turns on oil," Oswald says.

Consumers are the first to feel the deflationary effects of rising crude prices at the petrol pumps, with the impact only gradually being felt on the bottom line of companies. Unemployment goes up, but only after a lag.

There are three possible scenarios for prices over the next year. Scenario one, that they stay at around today's level of US$45 a barrel, looks the least likely, both because the oil price is so volatile and because the high oil price affects global output and hence oil prices themselves through a feedback mechanism. If US$50 crude prices kill off the global recovery, that will affect demand for fuel and hence its price.

Scenario two is that prices go a lot higher and stay there. This could be the result of one big shock, a terrorist attack that took out Saudi production for a prolonged period, for instance, or a series of little shocks -- a strike in Venezuela, a stand-off between President Putin and Yukos, a number of terrorist strikes on softer residential oil compounds

in the Middle East, a couple of tankers running aground -- that together are enough to push the price well over US$50 a barrel.

While that would be a lot lower in real inflation-adjusted terms than the record levels seen at the start of the 1980s (US$80 a barrel in today's money), it would still be enough to cause severe disruption to the West, and perhaps even push some economies into full-scale recession.

Finally, scenario three is where everything works out fine. There are no more attacks in the Middle East, Yukos and Putin kiss and make up, signs of an easing in growth blow the speculative froth off the market just as the incentive of higher prices encourages supply to increase. Then it's not impossible to envisage prices at US$25 a barrel by this time next year.

Without question, rising oil prices add to the problems facing policymakers. The difficulty they have is that the initial impact is inflationary, pushing up prices and costs, while the second-round effects are deflationary, affecting consumer incomes and corporate cash flow. What policymakers would like is for wage bargainers to take the hit from more expensive oil rather than seek compensatory pay increases, and for companies to refrain from passing on their higher costs to their consumers.

If they don't, the response will be higher interest rates, which will add to the deflationary impact of the oil shock and thereby increase the risk of a hard landing. In the UK, where the labor market is relatively tight, this autumn will be crucial, because individuals are getting a double whammy from higher oil prices and higher interest rates.

Little wonder, then, that some analysts think base rates could go a lot higher, to 6 percent or more. That's a possibility but by no means a certainty.

The last couple of months have seen straws in the wind that suggest that consumer behavior may be changing. Looking through the blizzard of wildly differing reports of the housing market, there is at least a hint that activity is slowing and that prices have -- none too soon -- topped out. New car registrations have fallen in the past three months, another indication that higher interest rates are making people think twice when it comes to big-ticket items.

August is a funny month. The world often looks a completely different place on a crisp September morning than it did in the heat of late July. The assumption is that the Bank of England is intent on tightening policy over the coming months, but its decisions will depend on the data.

If the data is weak, as it may be, interest rates may be close to their peak.

As strategic tensions escalate across the vast Indo-Pacific region, Taiwan has emerged as more than a potential flashpoint. It is the fulcrum upon which the credibility of the evolving American-led strategy of integrated deterrence now rests. How the US and regional powers like Japan respond to Taiwan’s defense, and how credible the deterrent against Chinese aggression proves to be, will profoundly shape the Indo-Pacific security architecture for years to come. A successful defense of Taiwan through strengthened deterrence in the Indo-Pacific would enhance the credibility of the US-led alliance system and underpin America’s global preeminence, while a failure of integrated deterrence would

It is being said every second day: The ongoing recall campaign in Taiwan — where citizens are trying to collect enough signatures to trigger re-elections for a number of Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) legislators — is orchestrated by the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP), or even President William Lai (賴清德) himself. The KMT makes the claim, and foreign media and analysts repeat it. However, they never show any proof — because there is not any. It is alarming how easily academics, journalists and experts toss around claims that amount to accusing a democratic government of conspiracy — without a shred of evidence. These

Taiwan is confronting escalating threats from its behemoth neighbor. Last month, the Chinese People’s Liberation Army conducted live-fire drills in the East China Sea, practicing blockades and precision strikes on simulated targets, while its escalating cyberattacks targeting government, financial and telecommunication systems threaten to disrupt Taiwan’s digital infrastructure. The mounting geopolitical pressure underscores Taiwan’s need to strengthen its defense capabilities to deter possible aggression and improve civilian preparedness. The consequences of inadequate preparation have been made all too clear by the tragic situation in Ukraine. Taiwan can build on its successful COVID-19 response, marked by effective planning and execution, to enhance

Since taking office, US President Donald Trump has upheld the core goals of “making America safer, stronger, and more prosperous,” fully implementing an “America first” policy. Countries have responded cautiously to the fresh style and rapid pace of the new Trump administration. The US has prioritized reindustrialization, building a stronger US role in the Indo-Pacific, and countering China’s malicious influence. This has created a high degree of alignment between the interests of Taiwan and the US in security, economics, technology and other spheres. Taiwan must properly understand the Trump administration’s intentions and coordinate, connect and correspond with US strategic goals.