For centuries the world's most outward-going and expansionist continent, Europe has now become inward-looking and self-absorbed.

From being the place to view and understand the dynamics of the world -- remember Paris, London or even Rome in the 1960s -- it no longer provides such a vantage point.

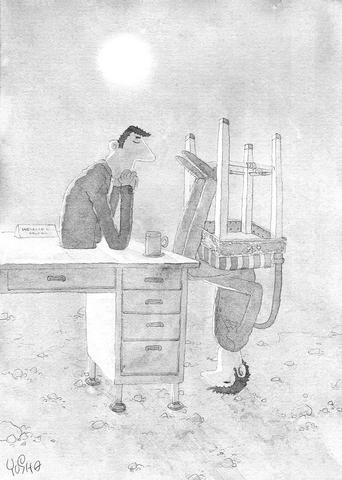

YUSHA

The engines of change have moved elsewhere. Of course, Europeans -- including the British -- do not recognize this. They still think that Europe, the US apart, is the center of the world. But this hubris, which is a product of history, has an increasingly tenuous purchase on the present. Indeed, the fact that Europeans are still largely unaware of this slippage in their global importance is itself powerful confirmation of the growing provincialism of our continent.

The integration project, which has dominated the life of Europe for almost half a century, has served to reinforce and accentuate this sense of introversion, even at times acted as the author of it.

This is not surprising. It has been a huge, difficult and novel undertaking. It has commanded the energy, brains and focus of the continent, directing them towards the nature, boundaries and arrangements of Europe rather than the wider world. The result has been self-absorption: it may have been inevitable, even desirable, but the effect has been no less real for that.

Of course, when Europe was the world's top dog, then these arrangements and preoccupations would have assumed automatic global significance, just as what happens now in Washington or New York is not simply an American, or even Western, matter, but also a global one. For Europe, though, this equation no longer holds: events on our continent are increasingly of regional rather than global concern.

There is a profound failure to grasp this shift in the order of things among many Europeans. There is an assumption that what we are doing still enjoys global resonance and meaning. Take the question of the nation state, for example. Part of the conventional wisdom that lies behind the rationale for the EU is that the nation state is in decline, hence the need for a larger institution which has the potential to be a global player. It has been assumed, moreover, that the decline of the nation state is not simply a European phenomenon but also a global one.

In fact, this is European hubris. In reality, the decline of the European nation state is a regional rather than global phenomenon, a product of the precipitous decline over the past 60 years of the European imperial powers. For the majority of nation states, products of colonial liberation and for whom an independent nation state is an entirely novel experience, the opposite is the case. For them, the building of a strong nation state has been the central objective. The results have inevitably been varied, but if we take the instance of East Asia, home to a third of the world's population, then the project has been hugely successful: the vast majority of nation states have seen a steady accretion of power -- the opposite to the European experience.

There has also been a strong tendency on the part of Europeans to see the EU as a global template for the future. In a Demos (an independent think tank based in London) pamphlet several years ago, Robert Cooper, a former adviser to Tony Blair and an intellectual architect of liberal imperialism, argued that the EU was the model of the future, the laboratory of a new kind of postmodern state. But does Europe prefigure a future for the rest of the world or is it, in fact, more accurately to be seen as the exception rather than the rule? It is not difficult to see echoes of the European integrationist project in regional experiments in other parts of the world, for example NAFTA, Mercosur in Latin America, and perhaps most relevantly of all, ASEAN in south-east Asia, which is a conscious attempt to enhance the power of its member states through the creation of a regional body, even though the latter so far amounts to little more than a free trade organization.

Such tendencies, though, can hardly be described as the dominant ones of our time. On the contrary, the era we have now entered would be more appropriately described as the moment of the nation state.

The emergence of the US as the sole superpower, its turn towards unilateralism, thereby weakening the trend towards multilateralism and global governance, is a quintessential demonstration of the power of the nation state, in some respects in excess of anything seen before. And the most likely challenge to its position of global pre-eminence will come not from the EU but China and India, which both represent a new kind of nation state, not least in terms of the immensity of their populations. From this perspective, the European experiment seems more like a subaltern than dominant trend.

The end of the Cold War, the US' unilateralism, and the consequent erosion of the notion and importance of "the West," have served to accelerate the decline in Europe's significance. With the fault line of the Cold War bisecting the continent, Europe was its global epicenter. The Western alliance sustained Europe's position and power in the world, even though the alliance was always much more a reflection of American strength than its own.

The contrasting importance of the two, indeed, has been manifest for some time: I was struck during the 1990s on my many visits to East Asia how hugely important the US was in a myriad of ways -- not least in the popular imagination -- and how invisible, even, alas, insignificant, Europe appeared to be: the term "west" served to obscure and obfuscate the reality.

Later, upon my return to London after living in East Asia and witnessing an extraordinary historical transformation, I was taken aback by the sheer ignorance of what was happening -- how Europeans had not understood its significance -- not least for themselves -- and by their provincialism (in which the elite is no exception).

European self-absorption will surely continue. Europe will remain preoccupied and troubled by the integration process for a long time to come, not least because the project is bureaucratically driven -- as it must be -- in a continent which is historically the home to democracy and popular sovereignty, a contradiction that lies at the heart of the project and always will.

At the same time Europe, historical home to virulent racism and not only democracy, is finding it enormously difficult to open itself to the world in terms of migration, to become multiracial, to extend to other races and cultures a pluralism that white European societies once imposed on them, to redefine and rethink itself in the context of a world where it is no longer the top dog. The net result will be not only gross introspection and many discordant voices but also, and inevitably, an inability to concert the power of Europe at an international level, be it politically or militarily.

Europe will continue to matter. It remains a great economic power. But the center of gravity is shifting remorselessly, with the result that Europe will no longer be a power in its own right, but rather a check on the power of others, notably the US, as France illustrated in the case of Iraq.

Martin Jacques is a visiting fellow at the London School of Economics Asia Research Center.

In their recent op-ed “Trump Should Rein In Taiwan” in Foreign Policy magazine, Christopher Chivvis and Stephen Wertheim argued that the US should pressure President William Lai (賴清德) to “tone it down” to de-escalate tensions in the Taiwan Strait — as if Taiwan’s words are more of a threat to peace than Beijing’s actions. It is an old argument dressed up in new concern: that Washington must rein in Taipei to avoid war. However, this narrative gets it backward. Taiwan is not the problem; China is. Calls for a so-called “grand bargain” with Beijing — where the US pressures Taiwan into concessions

The term “assassin’s mace” originates from Chinese folklore, describing a concealed weapon used by a weaker hero to defeat a stronger adversary with an unexpected strike. In more general military parlance, the concept refers to an asymmetric capability that targets a critical vulnerability of an adversary. China has found its modern equivalent of the assassin’s mace with its high-altitude electromagnetic pulse (HEMP) weapons, which are nuclear warheads detonated at a high altitude, emitting intense electromagnetic radiation capable of disabling and destroying electronics. An assassin’s mace weapon possesses two essential characteristics: strategic surprise and the ability to neutralize a core dependency.

Chinese President and Chinese Communist Party (CCP) Chairman Xi Jinping (習近平) said in a politburo speech late last month that his party must protect the “bottom line” to prevent systemic threats. The tone of his address was grave, revealing deep anxieties about China’s current state of affairs. Essentially, what he worries most about is systemic threats to China’s normal development as a country. The US-China trade war has turned white hot: China’s export orders have plummeted, Chinese firms and enterprises are shutting up shop, and local debt risks are mounting daily, causing China’s economy to flag externally and hemorrhage internally. China’s

During the “426 rally” organized by the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and the Taiwan People’s Party under the slogan “fight green communism, resist dictatorship,” leaders from the two opposition parties framed it as a battle against an allegedly authoritarian administration led by President William Lai (賴清德). While criticism of the government can be a healthy expression of a vibrant, pluralistic society, and protests are quite common in Taiwan, the discourse of the 426 rally nonetheless betrayed troubling signs of collective amnesia. Specifically, the KMT, which imposed 38 years of martial law in Taiwan from 1949 to 1987, has never fully faced its