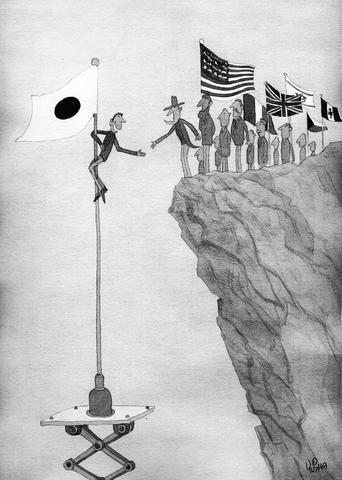

Every country that has sent troops to aid America's war and occupation in Iraq is under pressure, as the decision by the Philippines to withdraw its small contingent shows.

But for Japan, the question of whether to continue to aid for Iraq's reconstruction extends beyond the merits of this particular policy and goes to the heart of Japanese notions of security and what constitutes the national interest.

Throughout the Cold War, Japan's national security policy appeared to waver between "UN first" and "alliance first" principles. In essence, its alliance with the US dominated Japan's course. That tendency remains dominant.

YUSHA

But the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks on the US helped Japan recognize that it had to exercise greater autonomy and independent judgment in its national security policies. The paradigm of international security that had long dominated Japan's military thinking had shifted, and policymakers realized that they had to shift with it.

For Japan nowadays, security policy must satisfy a trinity of criteria: national interests, alliance, and international cooperation.

This trinity is not something new for Japan, but has deep historical roots. It may be helpful to look back to Japanese actions at the time of the Boxer Rebellion (1900), as well as during World War I.

Of course, there are huge differences between the situations then and what Japan faces now. But those historical contexts shed light on Japan's response to events in Iraq and the wider world today.

At the time of the Boxer Rebellion, Japan responded to requests for help from the international community and won world trust through the sacrifices it made.

As a consequence, and despite the anti-Japanese "yellow peril" propaganda then raging in Europe, Japan entered an alliance with the most sought-after partner of the time, Great Britain. That alliance enabled Japan to help defeat Russia in the Russo-Japanese War (1904-1905).

During the World War I, however, Japan was reluctant to send troops to Europe despite repeated requests from its allies. Although Japan did receive some appreciation for its dispatch of naval squadrons to the Mediterranean, it endured wide criticism for its refusal to send ground troops.

As a consequence, after that war Japan lost Britain's confidence, which eventually resulted in the end of the Anglo-Japanese alliance. From that time on, Japan trod a lonely path that ended with its defeat in World War II.

At the time of the Boxer Rebellion, Japan understood that to contribute to the world for the "emergency protection of foreign residents" was a matter of national importance.

During World War I, on the other hand, Japan was blinded by its eagerness to protect small but immediate benefits, and failed to appreciate what a true "matter of national importance" was. Its passivity cost Japan the trust of the international community.

In the light of this history, how should Japan's stance in Iraq be viewed? Will Japan's humanitarian aid in Iraq secure a long-term national interest?

With the exception of terrorists and remnants of former president Saddam Hussein's regime, almost everyone, including Iraqis who eye America's occupying forces with suspicion, wishes to see Iraq rebuilt, both politically and materially. For Japan, too, there is justification in responding to such global expectations.

Of course, restoring peace and security is taking much more time than expected.

With almost daily terrorist attacks, ordinary citizens victimized by weapons fire and misconceived bombing, the abuses of Iraqi prisoners and the hostility of Iraq's Shiites -- on whom the US had pinned high hopes for the peace process -- American policy is in danger of failing.

The question for Japan is this: what will happen, both in Iraq and in the world, if America withdraws in failure? It is in recognition of the possible consequences -- bolder terrorists and a return of US isolationism -- that many countries sent and retain troops in Iraq.

Indeed, Russia, France and Germany, which confronted the US and Britain at the UN over the Iraq war, and the UN itself, which withdrew early in the occupation, are all now searching for ways to assist in Iraq's rehabilitation.

In the end, they agreed on international efforts under UN Security Council Resolution 1546. France and Germany will now participate by helping to train Iraqi security forces.

Considering all this, Iraq represents a decisive moment and a "matter of national importance" for Japan. Thus its Self Defense Forces must continue their humanitarian and restoration efforts while cooperating with Japan's key ally, the US, as a member of an integrated multinational force under UN leadership.

Even if dangerous situations arise, Japan must not flinch. Only by demonstrating dignified resolve will Japan's national interests be defended.

True autonomy for Japan, as in the past, depends on active and cooperative engagement in containing a world crisis.

Hideaki Kaneda is a retired vice admiral in Japan's Self Defense Forces and is currently director of the Okazaki Institute.

Copyright: Project Syndicate

As strategic tensions escalate across the vast Indo-Pacific region, Taiwan has emerged as more than a potential flashpoint. It is the fulcrum upon which the credibility of the evolving American-led strategy of integrated deterrence now rests. How the US and regional powers like Japan respond to Taiwan’s defense, and how credible the deterrent against Chinese aggression proves to be, will profoundly shape the Indo-Pacific security architecture for years to come. A successful defense of Taiwan through strengthened deterrence in the Indo-Pacific would enhance the credibility of the US-led alliance system and underpin America’s global preeminence, while a failure of integrated deterrence would

It is being said every second day: The ongoing recall campaign in Taiwan — where citizens are trying to collect enough signatures to trigger re-elections for a number of Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) legislators — is orchestrated by the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP), or even President William Lai (賴清德) himself. The KMT makes the claim, and foreign media and analysts repeat it. However, they never show any proof — because there is not any. It is alarming how easily academics, journalists and experts toss around claims that amount to accusing a democratic government of conspiracy — without a shred of evidence. These

Taiwan is confronting escalating threats from its behemoth neighbor. Last month, the Chinese People’s Liberation Army conducted live-fire drills in the East China Sea, practicing blockades and precision strikes on simulated targets, while its escalating cyberattacks targeting government, financial and telecommunication systems threaten to disrupt Taiwan’s digital infrastructure. The mounting geopolitical pressure underscores Taiwan’s need to strengthen its defense capabilities to deter possible aggression and improve civilian preparedness. The consequences of inadequate preparation have been made all too clear by the tragic situation in Ukraine. Taiwan can build on its successful COVID-19 response, marked by effective planning and execution, to enhance

Since taking office, US President Donald Trump has upheld the core goals of “making America safer, stronger, and more prosperous,” fully implementing an “America first” policy. Countries have responded cautiously to the fresh style and rapid pace of the new Trump administration. The US has prioritized reindustrialization, building a stronger US role in the Indo-Pacific, and countering China’s malicious influence. This has created a high degree of alignment between the interests of Taiwan and the US in security, economics, technology and other spheres. Taiwan must properly understand the Trump administration’s intentions and coordinate, connect and correspond with US strategic goals.