In progressive liberal circles, the demand that the preamble to the constitution of the EU include a reference to God and/or the "Christian Roots" of Europe has been met with derision, even contempt. Such a reference, it is said, would run afoul of the common European constitutional tradition of state neutrality in matters of religion. It would also offend against Europe's political commitment to a tolerant, multicultural society. But the opposite is true: a reference to God is both constitutionally permissible and politically imperative.

Constitutionally, European nations display characteristic richness. As a matter of positive constitutional law, all members of the EU, under the tutelage of the European Convention on Human Rights, are committed to the principle of the "Agnostic or Impartial State," which guarantees both freedom of religion and freedom from religion. Across Europe, there is a remarkable degree of homogeneity -- even if on some borderline issues such as religious headgear in schools or crucifixes, different EU member states balance differently the delicate line between freedom of religion and freedom from religion.

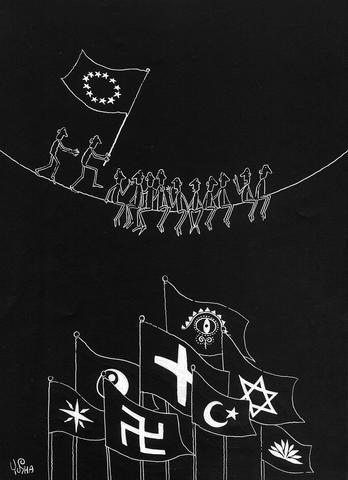

YUSHA

But when it comes to constitutional symbolism and iconography, Europe is remarkably heterogeneous. At one extreme you find countries like France, whose constitution defines the state as secular. At the other extreme are countries like Denmark and the UK, where there is an established state religion.

In the UK, the sovereign is not only head of state but also head of the church. In between are states like Germany, whose constitutional preamble makes an explicit reference to God, or Ireland, where the preamble refers to the Holy Trinity.

All in all, about half the population of the EU lives in states whose constitutions make an explicit reference to God and/or Christianity. What is remarkable about Europe -- a value to be cherished -- is that even in such states, the principle of freedom of religion and freedom from religion are fully respected. No one could credibly argue that, say, Denmark is less committed to liberal democracy or is less tolerant than, say, France or Italy, despite the fact that Denmark recognizes an official state church and France and Italy are avowedly secular.

In its substantive provisions, the European Constitution reflects the homogeneity of the European constitutional tradition. It is fully committed to the notions of freedom of religion and freedom from religion, as it should be.

But when it comes to the preamble, the EU constitution should reflect European heterogeneity. It should reflect the European commitment to the noble heritage of the French Revolution, as reflected in, say, the French Constitution, but it should reflect in equal measure the symbolism of those constitutions that include an Invocatio Dei.

The refusal to make a reference to God is based on the false argument that confuses secularism with neutrality or impartiality. The preamble has a binary choice: yes to God, no to God. Why is excluding a reference to God any more neutral than including God? It is favoring one worldview, secularism, over another worldview, religiosity, masquerading as neutrality. How, then, can one respect both traditions?

The new Polish Constitution gives an elegant answer: It acknowledge both traditions: "We, the Polish Nation -- all citizens of the Republic, both those who believe in God as the source of truth, justice, good and beauty, as well as those not sharing such faith but respecting those universal values as arising from other sources, equal in rights and obligations towards the common good ... "

A similar solution should be found for the European constitution. Europe cannot preach cultural pluralism and practice constitutional imperialism. Indeed, the political imperative is as great as the constitutional one.

Europe, after all, is committed to democracy worldwide. But in the European way of thinking, democracy must be spread pacifically, by persuasion, not by force of arms. One of the greatest obstacles to the spread of democracy is the widely held view that religion and democracy are inimical to each other: to adopt democracy means to banish God and religion from the public sphere and make it strictly a private affair.

Indeed, that is the message that the Franco-American model of constitutional democracy sends to the world. But is the particular relationship between church and state at the time of the French and American Revolutions the model that Europe wishes to propagate in the rest of the world today? Is the European constitution to proclaim that God is to be chased out of the public space? How long must we be prisoners of that historical experience?

The state has changed, and the church has changed even more. In this area, as in many others, Europe can lead by example and offer an alternative to American (and French) constitutional separationism. It can be a living illustration that religion is no longer afraid of democracy and that democracy is no longer afraid of religion.

The truest pluralism is embodied by states that can, on the one hand, effectively guarantee both religious freedom and freedom from religion, yet acknowledge without fear -- even in their constitutions -- the living faith of many of their citizens. Only this model has any chance of persuading societies that still view democracy with suspicion and hostility.

Joseph Weiler is university professor and Jean Monnet chair and director of the Global Law School Program, New York University School of Law. His book Un Europa Cristiana has recently been published in Italy, Spain, Portugal and Poland.

Copyright: Project Syndicate/Institute for Human Sciences

In their recent op-ed “Trump Should Rein In Taiwan” in Foreign Policy magazine, Christopher Chivvis and Stephen Wertheim argued that the US should pressure President William Lai (賴清德) to “tone it down” to de-escalate tensions in the Taiwan Strait — as if Taiwan’s words are more of a threat to peace than Beijing’s actions. It is an old argument dressed up in new concern: that Washington must rein in Taipei to avoid war. However, this narrative gets it backward. Taiwan is not the problem; China is. Calls for a so-called “grand bargain” with Beijing — where the US pressures Taiwan into concessions

The term “assassin’s mace” originates from Chinese folklore, describing a concealed weapon used by a weaker hero to defeat a stronger adversary with an unexpected strike. In more general military parlance, the concept refers to an asymmetric capability that targets a critical vulnerability of an adversary. China has found its modern equivalent of the assassin’s mace with its high-altitude electromagnetic pulse (HEMP) weapons, which are nuclear warheads detonated at a high altitude, emitting intense electromagnetic radiation capable of disabling and destroying electronics. An assassin’s mace weapon possesses two essential characteristics: strategic surprise and the ability to neutralize a core dependency.

Chinese President and Chinese Communist Party (CCP) Chairman Xi Jinping (習近平) said in a politburo speech late last month that his party must protect the “bottom line” to prevent systemic threats. The tone of his address was grave, revealing deep anxieties about China’s current state of affairs. Essentially, what he worries most about is systemic threats to China’s normal development as a country. The US-China trade war has turned white hot: China’s export orders have plummeted, Chinese firms and enterprises are shutting up shop, and local debt risks are mounting daily, causing China’s economy to flag externally and hemorrhage internally. China’s

During the “426 rally” organized by the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and the Taiwan People’s Party under the slogan “fight green communism, resist dictatorship,” leaders from the two opposition parties framed it as a battle against an allegedly authoritarian administration led by President William Lai (賴清德). While criticism of the government can be a healthy expression of a vibrant, pluralistic society, and protests are quite common in Taiwan, the discourse of the 426 rally nonetheless betrayed troubling signs of collective amnesia. Specifically, the KMT, which imposed 38 years of martial law in Taiwan from 1949 to 1987, has never fully faced its