Long ago, the acclaimed and extraordinarily pro-lific children's author, William Mayne, addressed a book conference. His speech is reported to have consisted of two words: "Any questions?" This aversion to public appearances became such that in 1998 he declined the chance to receive the Kurt Maschler award for an illustrated book, Lady Muck, explaining that he would be in Yorkshire that night, organizing a nativity play.

The following year, a woman went to the police with allegations of sexual assaults committed in the 1960s by Mayne, who is now 76. Other allegations followed, and last month, having first denied the charges in court, Mayne admitted having sexually abused the little girls who had visited his home four decades ago. A jury was directed by the judge to return not-guilty verdicts on two rape charges.

Prior to his two-and-a-half-year prison sentence, a series of women now in middle age described how he had "groomed" children he later assaulted; keeping an open house and encouraging what he called "romping,"

YUSHA

According to two of his victims, Mayne would tell them that subsequent sexual assaults were "what we wanted. It is only what girls want. The message we got was that he was only doing what we wanted."

Will anyone, having read such details, want to read stories by Mayne again? Or want their children to read them? Even if they are innocent as can be, his stories for younger readers, about a bobbed, big-eyed seven-year-old called Netta, can hardly escape being contaminated by the interest we now understand he took in eight-year-olds. Then again, a book cannot be judged by its author.

Lewis Carroll's pictures of naked girls do not stop us from reading Alice in Wonderland. Eric Gill's carvings weren't shrouded after the revelations of incest and bestiality. Mayne's achievement of 60 or so titles, written over half a century, remains what it was when Philip Pullman admired "the rare and intense quality" of his work; when a panel led by Anne Fine awarded him the 1993 Guardian Children's Fiction Award, and when the Times Literary Supplement described him as "the most original good writer for young people in our time."

Mayne's publishers are cautious. Walker Books is withdrawing its Mayne titles from bookshops, and Jonathan Cape has "postponed" a book called Emily Goes to Market, which should have been published this month. Hodder Children's Books has put "on hold" one novel due out next year, and, according to Charles Nettleton, managing director, will assess the response from its customers in schools, bookstores and libraries before issuing further reprints. "We are trying not to make any judgments," he says. "If we find that nobody is ordering his books anymore, it makes it pointless to publish."

For the schools, bookstores and libraries which are now effectively entrusted with Mayne's oeuvre, this is quite a responsibility. If his crimes did justify the purging of every Mayne title from public display, this would be a precedent, surely, for reconsidering the position of all sorts of authors, from William Burroughs (killed his wife) and Jeffrey Archer, (sentenced for perjury), not to mention a reassessment of the claims of numerous misfits and demi-creeps -- Dodgson, Barrie, AA Milne, Kingsley, Grahame -- who double as luminaries of children's literature.

Arguably, if the best children's writing emerges from a special, unusually powerful connection with childhood -- sometimes through a personal inability to leave it behind -- then the best children's authors are always likely to include the significantly messed up. It almost amounts to a qualification.

What would single Mayne out for unusually harsh punishment, however, would be the discovery that his books were designed to corrupt, by somehow legitimizing or promoting the activities for which he was jailed. Just because no one perceived irregularities in his work before Mayne's conviction does not mean that, like Archer, whose literature is full of the love of cheap tricks, the books are not squalidly consistent with his crimes.

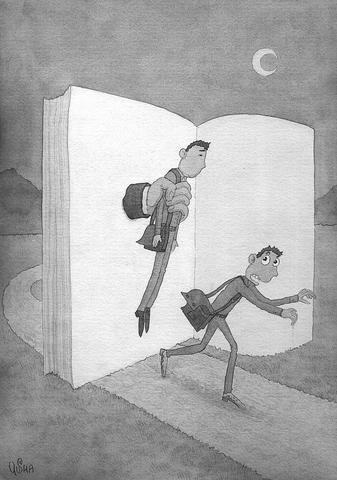

Looking at a few of them this week, Mayne's stories seem to be blameless even if one of their particular attractions for a child -- the regular escapes from the harsh, adult-run world, often into a different place altogether -- cannot but echo, for an adult reader, Mayne's real efforts to establish private complicities and relations with children behind the backs of their families. In Pig in the Middle, a boy, Michael, swears to sail a barge to Holland, "And he had sworn away not only his brother, but the rest of his family and everything that he knew."

In A Game of Dark, Donald tells his grown-up confidant, a priest, that he doesn't like his father. The priest (earlier seen persuading the boy to take deep drags of his cigarette), reassures him that, "When I was about 15 I despised my father."

With hindsight, Mayne's particular gift for conveying, in prose of great assurance and spareness, the way in which children's minds work also speaks of a fascination with juveniles that occasionally, criminally, knew no limits. Maybe this degree of familiarity, combined with his preference for primary-school visits (accompanied by a bear called Beowulf) over sales conferences should have been accepted less matter-of-factly.

But if Mayne's unbounded interest in children can be divided into good and bad parts, then the books, belonging to the former category, should perhaps be allowed to carry on speaking for themselves.

At Hodder, Nettleton says his view is that Mayne's conviction "wouldn't necessarily stop me reading one of his books, or giving one to a child if I thought it was a good book. I think the books do stand on their own merits; this [criminal conviction] doesn't at all detract from whatever qualities they have."

He points out that, as publishers of the Bible and Pilgrim's Progress, Hodder has no problem with writers who have been prison inmates. On the other hand, he admits to feeling uneasy.

"Because of the nature of the offense, there may have been a bond of trust that has been broken there. It's very sad," he said.

It is. Having repeatedly read one of his books (A Parcel of Trees) as a child and emerged unscathed from these intoxicating encounters with Mayne, it seems unreasonably vengeful, not to say pointless, to deny other children the same access to his books. It is the private access from Mayne to children who might have struck him as likely sexual partners from which, however irrationally, one recoils. I was far from sorry to find my nearest seven-year-old has but one Mayne in her possession: an illustrated book called Pandora, about a cat who feels unwanted by her family, and runs away from home.

In their recent op-ed “Trump Should Rein In Taiwan” in Foreign Policy magazine, Christopher Chivvis and Stephen Wertheim argued that the US should pressure President William Lai (賴清德) to “tone it down” to de-escalate tensions in the Taiwan Strait — as if Taiwan’s words are more of a threat to peace than Beijing’s actions. It is an old argument dressed up in new concern: that Washington must rein in Taipei to avoid war. However, this narrative gets it backward. Taiwan is not the problem; China is. Calls for a so-called “grand bargain” with Beijing — where the US pressures Taiwan into concessions

The term “assassin’s mace” originates from Chinese folklore, describing a concealed weapon used by a weaker hero to defeat a stronger adversary with an unexpected strike. In more general military parlance, the concept refers to an asymmetric capability that targets a critical vulnerability of an adversary. China has found its modern equivalent of the assassin’s mace with its high-altitude electromagnetic pulse (HEMP) weapons, which are nuclear warheads detonated at a high altitude, emitting intense electromagnetic radiation capable of disabling and destroying electronics. An assassin’s mace weapon possesses two essential characteristics: strategic surprise and the ability to neutralize a core dependency.

Chinese President and Chinese Communist Party (CCP) Chairman Xi Jinping (習近平) said in a politburo speech late last month that his party must protect the “bottom line” to prevent systemic threats. The tone of his address was grave, revealing deep anxieties about China’s current state of affairs. Essentially, what he worries most about is systemic threats to China’s normal development as a country. The US-China trade war has turned white hot: China’s export orders have plummeted, Chinese firms and enterprises are shutting up shop, and local debt risks are mounting daily, causing China’s economy to flag externally and hemorrhage internally. China’s

During the “426 rally” organized by the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and the Taiwan People’s Party under the slogan “fight green communism, resist dictatorship,” leaders from the two opposition parties framed it as a battle against an allegedly authoritarian administration led by President William Lai (賴清德). While criticism of the government can be a healthy expression of a vibrant, pluralistic society, and protests are quite common in Taiwan, the discourse of the 426 rally nonetheless betrayed troubling signs of collective amnesia. Specifically, the KMT, which imposed 38 years of martial law in Taiwan from 1949 to 1987, has never fully faced its