Three decades ago, the radical left used the term "American empire" as an epithet. Now that same term has come out of the closet: analysts on both the left and right now use it to explain -- if not guide -- American foreign policy.

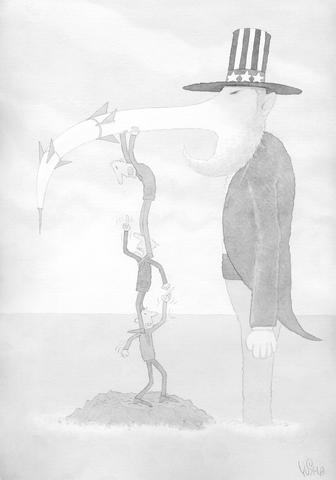

In many ways, the metaphor of empire is seductive. The American military has a global reach, with bases around the world, and its regional commanders sometimes act like proconsuls. English is a lingua franca like Latin. The US economy is the largest in the world, and American culture serves as a magnet. But it is a mistake to confuse primacy with empire.

The US is certainly not an empire in the way we think of the European empires of the 19th and 20th centuries, because the core feature of that imperialism was political power. Although unequal relationships between the US and weaker powers certainly exist and can be conducive to exploitation, the term "imperial" is not only inaccurate but misleading in the absence of formal political control.

YUSHA

To be sure, the US now has more power resources relative to other countries than Britain had at its imperial peak. But the US has less power -- in the sense of control over other countries' internal behavior -- than Britain did when it ruled a quarter of the globe.

For example, British officials controlled Kenya's schools, taxes, laws and elections -- not to mention its external relations. America has no such control today. Last year, the US could not even get Mexico and Chile to vote to support a second resolution on Iraq in the UN Security Council.

Devotees of the New Imperialism would say, "Don't to be so literal." After all, "empire" is merely a metaphor. But the problem with the metaphor is that it implies a degree of American control that is unrealistic, and reinforces the prevailing strong temptations toward unilateralism in both the US Congress and parts of President George W. Bush's administration.

In the global information age, strategic power is simply not so highly concentrated. Instead, it is distributed among countries in a pattern that resembles a complex three-dimensional chess game. On the top chessboard, military power is largely unipolar, but on the economic board, the US is not a hegemon or an empire, and it must bargain as an equal when, for example, Europe acts in a unified way. On the bottom chessboard of transnational relations, power is chaotically dispersed, and it makes no sense to use traditional terms such as unipolarity, hegemony, or American empire.

So those who recommend an imperial US foreign policy based on traditional military descriptions of American power are woefully misguided. In a three-dimensional game, you will lose if you focus only on one board and fail to notice the other boards and the vertical connections among them.

Witness the connections in the war on terrorism between military actions on the top board, where the US removed a tyrant in Iraq, but simultaneously increased the ability of al-Qaeda to gain new recruits on the bottom transnational board.

These issues represent the dark side of globalization. They are inherently multilateral and require cooperation for their solution. So to describe America as an empire fails to capture the true nature of the foreign policy challenges that America faces.

Those who promote the idea of an American empire also mis-understand the underlying nature of American public opinion and institutions. Will the American public tolerate an imperial role? Neo-conservatives writers like Max Boot argue that the US should provide troubled countries with the sort of enlightened foreign administration once provided by self-confident Englishmen in pith helmets. But, as the British historian Niall Ferguson points out, modern America differs from 19th-century Britain in its "chronically short time frame."

America was briefly tempted into real imperialism when it emerged as a world power a century ago, but the interlude of formal empire did not last long. Unlike Britain, imperialism has never been a comfortable experience for Americans, and only a small share of its military occupations led directly to the establishment of democracies.

American empire is not constrained by economics: the US devoted a much higher percentage of its GDP to military spending during the Cold War than it does today. Its imperial overreach will instead come from having to police more peripheral countries than US public opinion will accept.

Indeed, opinion polls in America show little popular taste for empire and continuing support for multilateralism and using the UN.

Michael Ignatieff, a Canadian advocate of the imperial metaphor, qualifies it by referring to America's role in the world as "Empire Lite."

In fact, the problem of creating an American empire might better be termed imperial underreach. Neither the US public nor Congress has proven willing to invest seriously in the instruments of nation building and governance, as opposed to investment in military force.

Indeed, the entire State Department budget is only 1 percent of the federal budget. The US spends nearly 17 times as much on its military, and there is little indication that this is about to change.

So the US should avoid the misleading metaphor of empire as a guide to its foreign policy. Empire will not help America to cope with the challenges it faces in the global information age of the 21st century. Chess, anyone?

Joseph Nye, dean of Harvard University's Kennedy School of Government and a former assistant secretary of defense, is the author of The Paradox of American Power: Why the World's Only Superpower Can't Go It Alone.

copyright: project syndicate

A failure by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) to respond to Israel’s brilliant 12-day (June 12-23) bombing and special operations war against Iran, topped by US President Donald Trump’s ordering the June 21 bombing of Iranian deep underground nuclear weapons fuel processing sites, has been noted by some as demonstrating a profound lack of resolve, even “impotence,” by China. However, this would be a dangerous underestimation of CCP ambitions and its broader and more profound military response to the Trump Administration — a challenge that includes an acceleration of its strategies to assist nuclear proxy states, and developing a wide array

Eating at a breakfast shop the other day, I turned to an old man sitting at the table next to mine. “Hey, did you hear that the Legislative Yuan passed a bill to give everyone NT$10,000 [US$340]?” I said, pointing to a newspaper headline. The old man cursed, then said: “Yeah, the Chinese Nationalist Party [KMT] canceled the NT$100 billion subsidy for Taiwan Power Co and announced they would give everyone NT$10,000 instead. “Nice. Now they are saying that if electricity prices go up, we can just use that cash to pay for it,” he said. “I have no time for drivel like

Twenty-four Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) lawmakers are facing recall votes on Saturday, prompting nearly all KMT officials and lawmakers to rally their supporters over the past weekend, urging them to vote “no” in a bid to retain their seats and preserve the KMT’s majority in the Legislative Yuan. The Democratic Progressive Party (DPP), which had largely kept its distance from the civic recall campaigns, earlier this month instructed its officials and staff to support the recall groups in a final push to protect the nation. The justification for the recalls has increasingly been framed as a “resistance” movement against China and

Chinese Minister of Foreign Affairs Wang Yi (王毅) reportedly told the EU’s top diplomat that China does not want Russia to lose in Ukraine, because the US could shift its focus to countering Beijing. Wang made the comment while meeting with EU High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy Kaja Kallas on July 2 at the 13th China-EU High-Level Strategic Dialogue in Brussels, the South China Morning Post and CNN reported. Although contrary to China’s claim of neutrality in the Russia-Ukraine conflict, such a frank remark suggests Beijing might prefer a protracted war to keep the US from focusing on