America, the land that gave the world Coca-Cola, Titanic and the Marlboro Man, is having a hard time selling itself.

The government's public relations drive to build a favorable impression abroad -- particularly among Muslim nations -- is a shambles, according to lawmakers from both parties, State Department officials and independent experts. They say the effort, known as public diplomacy, lacks direction and is starved of cash and personnel.

Washington has failed to capitalize on the ouster of former Iraqi leader Saddam Hussein, these critics say, and did not maintain the sympathy generated by the Sept. 11 attacks. In Iraq, occupation officials routinely blame their miscalculations on pessimistic American news media, a reflex that even some hawks denounce as deceptive.

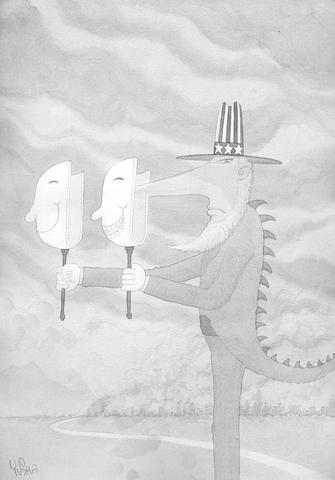

ILLUSTRATION MOUNTAIN PEOPLE

Public diplomacy is "a complete and utter disaster in Iraq," said Mark Helmke, a senior staff member on the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, who holds that the occupation authority has done little to counter criticism that it is an imperial, occupying force. "We have four different agencies running media operations there. There's no coordination, no strategy."

A senior State Department official, who is active in public diplomacy, says he starts his day pondering the antipathy to the US.

"Why, in Jordan, do people think Osama bin Laden is a better leader than George Bush?" he asked. "It's not just Arabs who are angry with the United States. It's worldwide."

Nearly two years ago, the Bush administration, hoping to tap the expertise of the private sector, hired Charlotte Beers, a Madison Avenue advertising whiz, as officials built their case for war with Iraq. After producing a feel-good video about Muslims in the US, which was rejected by some Arab nations -- and even scoffed at by some State Department colleagues -- Beers retired in March, citing health reasons.

Now, the administration is turning to an old government hand, Margaret Tutwiler. A former State Department spokeswoman and former ambassador to Morocco, it falls to her to convey the administration's intentions in the Middle East and elsewhere and to counter the virulent anti-Americanism that fosters terrorism.

As she settled into her offices this month, Tutwiler offered only a terse comment: "I hope that I am able to contribute to the overall public diplomacy efforts of our government."

The enthusiasm over her arrival is widespread. Colleagues said they expected her to ask Secretary of State Colin Powell, one of the administration's most popular figures, to embark on a "listening tour" in crucial Muslim nations.

Of course, nothing persuades like success. Some administration officials insist that tempers from Jakarta to Jidda will start to cool if security is established in Iraq and leadership is transferred.

The capture of Saddam, and the announcement by the Libyan leader, Muammar Qaddafi, that he will forswear unconventional weapons evinces a grudging respect for the administration's military strategy, but even some hard-liners voice doubts about the plan and how it is being promoted. Robert Novak, a syndicated columnist, recently cited the need for an overhaul of the American leadership in Iraq and "an end to the deceptive public relations favored by the inner circle at the Pentagon."

Some foreigners say all the fretting is overblown. Hesham El Nakib, a spokesman for the Egyptian Embassy in Washington, says that even the term "anti-Americanism" is too harsh.

"To say that it is like a wildfire is an overstatement," he said. "There are some resentments from the policies here and there."

Still, there is general agreement that the US rarely gets credit for the support it provides, especially in the Middle East. Nakib acknowledges that the average Egyptian may not be aware that the US is an ally that provides nearly US$2 billion in aid each year.

Many Muslims say that US policy favors Israelis over Palestinians and needs to be altered before sentiments will change. James Zogby, the president of the Arab American Institute, says the standoff weighs heavily throughout the Arab world. "The policy issues have taken a toll," he said.

Some Americans exploring ways to improve public diplomacy say they have been astonished by the depth of feeling on that issue.

"I was really shocked by the level of animosity over our policies toward Israel and the Palestinians, even in places like Turkey," said James Glassman, a journalist and resident fellow at the American Enterprise Institute, who served on a congressionally mandated advisory panel that toured the region this year.

Beyond the policy questions, experts say the American outreach has been hampered by inattention and the challenge of a changing world. These are among the problems they cite:

-- America's interlocutors in the Muslim world are increasingly seen as the backers of bankrupt regimes. For decades, the US looked to an elite, older generation of decision-makers -- judges, journalists, lawyers -- to cast US policies sympathetically. The younger generation has little connection with the US, beyond a taste for its fashions and entertainment.

-- Security concerns have undercut face-to-face diplomacy. Many American diplomats spend their days in fortress-like embassies and rely on secondhand accounts. One French diplomat recalled that an Arabic-speaking American envoy based in North Africa begged off from meetings with local residents because he was forbidden to leave his compound at night.

-- There is a lack of cultural knowledge of the Muslim world. Americans tend not to study Arabic and other languages and traditions of predominantly Muslim countries, preventing them from presenting their policies directly to people.

-- The State Department has had a back seat to the Pentagon in public diplomacy. The occupation destroyed, then took over the Iraqi national television station. A defense contractor, SAIC, hired to run the operation, broadcast on the same frequency used by the widely ridiculed Iraqi Ministry of Information; the contractor's contract will not be renewed, officials said.

-- Congress and successive administrations have cut the budgets for public diplomacy in recent years. A Republican-led reorganization folded the US Information Agency -- which included the Voice of America and Radio Free Europe -- into the State Department, reducing its number of employees by 40 percent.

"Our government probably made a mistake when they abolished USIA," said Representative Frank Wolf, who voted for the State Department reorganization in 1998. "Right now, we're not very successful in telling the good news."

In their recent op-ed “Trump Should Rein In Taiwan” in Foreign Policy magazine, Christopher Chivvis and Stephen Wertheim argued that the US should pressure President William Lai (賴清德) to “tone it down” to de-escalate tensions in the Taiwan Strait — as if Taiwan’s words are more of a threat to peace than Beijing’s actions. It is an old argument dressed up in new concern: that Washington must rein in Taipei to avoid war. However, this narrative gets it backward. Taiwan is not the problem; China is. Calls for a so-called “grand bargain” with Beijing — where the US pressures Taiwan into concessions

The term “assassin’s mace” originates from Chinese folklore, describing a concealed weapon used by a weaker hero to defeat a stronger adversary with an unexpected strike. In more general military parlance, the concept refers to an asymmetric capability that targets a critical vulnerability of an adversary. China has found its modern equivalent of the assassin’s mace with its high-altitude electromagnetic pulse (HEMP) weapons, which are nuclear warheads detonated at a high altitude, emitting intense electromagnetic radiation capable of disabling and destroying electronics. An assassin’s mace weapon possesses two essential characteristics: strategic surprise and the ability to neutralize a core dependency.

Chinese President and Chinese Communist Party (CCP) Chairman Xi Jinping (習近平) said in a politburo speech late last month that his party must protect the “bottom line” to prevent systemic threats. The tone of his address was grave, revealing deep anxieties about China’s current state of affairs. Essentially, what he worries most about is systemic threats to China’s normal development as a country. The US-China trade war has turned white hot: China’s export orders have plummeted, Chinese firms and enterprises are shutting up shop, and local debt risks are mounting daily, causing China’s economy to flag externally and hemorrhage internally. China’s

During the “426 rally” organized by the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and the Taiwan People’s Party under the slogan “fight green communism, resist dictatorship,” leaders from the two opposition parties framed it as a battle against an allegedly authoritarian administration led by President William Lai (賴清德). While criticism of the government can be a healthy expression of a vibrant, pluralistic society, and protests are quite common in Taiwan, the discourse of the 426 rally nonetheless betrayed troubling signs of collective amnesia. Specifically, the KMT, which imposed 38 years of martial law in Taiwan from 1949 to 1987, has never fully faced its