For a man whose name is so inextricably connected with death, Mikhail Kalashnikov could not have asked for a more tranquil twilight to his life. He spends his summer days at a country house on the bank of a crystalline lake, in the heart of the south Urals countryside, a few miles from the industrial heartland of Izhevsk.

Here, amid sky-high pines and mosquitoes the size of pigeons, he and his elfin granddaughter, Ilona, seven, play together at clearing wood, and breathe in the rich, clean air.

Yet for those around him, life is not so peaceful. Years of test-firing the automatic weapons that have both made and taken his name have left the 83-year-old very deaf indeed. If you want him to hear you, you have to put your mouth a few inches away from his ear and speak very loudly.

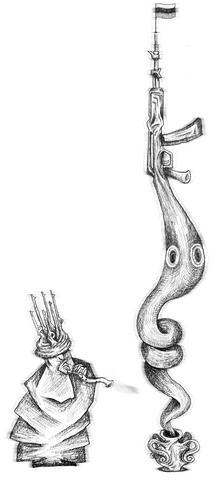

ILLUSTRATION: MOUNTAIN PEOPLE

In 1947 the Avtomatni Kalashnikova (Automatic of Kalashnikov) won a Soviet competition to design the ultimate sub-machine gun for the victorious Red Army. Fifty-six years, more than 100 million guns, and many millions of dead later, it remains the world's most prolific killing machine. But Kalashnikov is not the slightest bit reticent about showing the love and pride he still feels for his creation.

"You see, with [designing] weapons, it is like a woman who bears children," he says. "For months she carries her baby and thinks about it. A designer does much the same thing with a prototype. I felt like a mother -- always proud. It is a special feeling, as if you were awarded with a special award. I shot with it a lot. I still do now."

"That is why I am hard of hearing," he says.

According to Aaron Karp, senior consultant to the Geneva-based Small Arms Survey, Kalashnikov's progeny "appear to have caused most of the 300,000 annual combat fatalities in the wars of the 1990s."

They were the primary weapon for one or more sides in virtually all the 40-plus wars of the last decade.

It was perhaps the Soviet Union's key export: there are now 10 times as many AK-47s in the world as M16s, their American rival, the Soviets having given them away free to any movement they felt an empathy with or saw a use for.

The key to its success is its simple design, intended to ensure that even the unskilled women and children running the Soviet arms factories during wartime could mass-produce it for their fathers and sons on the front. It is so basic that crude versions have been produced in village workshops in Pakistan.

"Compared to other automatic rifles at the time," says Maxime Piadiyshev, editor of Arms Export Review, "it was very simple in production, use and maintenance, with eight moving parts. This simplicity meant a poorly trained soldier could strip it within 50 seconds and easily clean and maintain it."

But Kalashnikov seems to have found a way of absolving himself from any blame or responsibility for his baby's death toll. He offers a simple, well-honed defense to convince both himself and his interrogators of his innocence: "I made it to protect the motherland."

"And then they spread the weapon [around the world] -- not because I wanted them to. Not at my choice. Then it was like a genie out of the bottle and it began to walk all on its own and in directions I did not want," he says.

Yet "the positive has outweighed the negative," he insists, "because many countries use it to defend themselves. The negative side is that sometimes it is beyond control. Terrorists also want to use simple and reliable arms. But I sleep soundly. The fact that people die because of an AK-47 is not because of the designer, but because of politics."

To understand this enduring pride, you have to appreciate the Soviet mindset that still rules the elderly man. Earlier, Kalashnikov had described gleefully how much dead forest he and Ilona had shifted that afternoon.

His joy exposes the Soviet worship of trud -- a notion of labour and productivity that won him the Hero of Socialist Labour medal in 1976 for his inventions, and fuelled his ideas. For him, it was just his job, as a tiny cog in the greater Soviet enterprise.

It was only when he saw how the great communist project eventually perverted the original purpose of his "baby" that Kalashnikov began to feel any discomfort. He and his daughter point to two key moments when this happened. One was when hundreds of Azerbaijanis were massacred at Nagorno-Karabakh in 1992 by Armenians working with the reported help of the Russian army's 366th Motor Rifle Regiment. Kalashnikov admits that watching the television pictures of the massacre was "obviously unpleasant." The other was when former president Boris Yeltsin ordered troops to attack the capital's seat of government in 1993.

Kalashnikov's quiet life in the woods outside Izhevsk could be seen as an attempt to distance himself from what his invention has become. His warm and charismatic daughters dote on him. Elena organizes interviews. She lovingly translates -- or re-shouts -- my questions, beaming with attentiveness, warmth and pride.

Granddaughter Ilona keeps a sparkle in his eyes.

Meanwhile, a few miles away from this family haven, the weapon is still churned out in Izhevsk, and loudly advertised on the Izhmash company website.

In one hotel an American tourist wears an AK-47 "World Destruction Tour" T-shirt, the tour dates listed as "Chechnya, Afghanistan, the Gaza Strip, the Congo, Nagorno-Karabakh, etc". Down the road in one of the town's gun shops, Liliya, 12, and her friend stand and stare at the AK-47s on display.

"It's our first time here," she says. "We just wanted to see."

The new world of the Kalashnikov is the fall of an empire and two generations away from its inception. The story of how this original idea came about is deeply bound up with the story of Kalashnikov's life. Born to a poor peasant family just after the October revolution in November 1919, Mikhail Yefimiyevich Kalashnikov found his family exiled from the hills of the southern Altai region to Siberia, where they lived a hard farming existence.

Yet the exile -- the shame of a family outcast from the workers' dream of Soviet Russia -- spurred Kalashnikov into proving his worth.

"I was trying to perform as best as possible. I was a boy at the time, but worked well with the sickle," he says.

He would invent anything to make the life of his family, and the communist worker, easier.

"We had grain but no mills, so I designed a special mill of wood so we could make flour. I was probably born with some designing abilities," he says.

He was soon sent to work on the railways, as a clerk. Here his creative ambitions began to flourish.

"I wanted to invent an engine that could run for ever. I could have developed a new train, had I stayed in the railway. It would have looked like the AK-47 though," he jokes.

Aged 19, he was drafted into the army to serve in the second world war. Attached to a tank division, he soon found uses for his design skills. First it was a machine to count the number of shells fired by the tank's heavy machine gun, "so we would know how many we had left". Then it was a device that let their officer's pistols poke out through the tank's firing slots; then it was a method of measuring the distance covered by tanks.

The AK-47 began life as Kalashnikov sat in a war hospital recovering from wounds and shellshock, wondering how unfair it was that Germans had automatic weapons, and his fellow Russians only single-shot rifles.

"I tried a dozen different modifications that were rejected. But they all served as a path to the final design. I had to gain experience as I did not have a technical education," he says.

The process was long and competitive, Kalashnikov working to complete the design at a series of institutes, his ideas subject to criticism at every stage.

"The artillery department gave the specs for a new weapon. We had to improve on it or be eliminated from the contest," he says.

In 1946 the prototype AK-46 was born, a year later the real thing approved. He puts his success down to how "lucky I was to meet kind, helpful people all my life." He had a "good manager," Captain Vladimir Daikin, an encouraging head of department, Vladimir Glukhov, and a mentor, Anatoly Blagonravov, who first reported to his superiors in 1941 Kalashnikov's "exceptional ability to solve issues."

He portrays the final product as a perfect communist achievement -- a collective triumph that saved the motherland. To him, it seems as though the gun came about through something like natural selection, an invention that, in his last few years, he insists was born of survival and necessity, of being a young man thrust into war.

"Man keeps inventing things all the time," he says. "Life is composed of different inventions. I have continued to work at different things, and rebuilt my home all by myself. I did it for the sake of satisfaction at doing something. I did it because I happened to be where I was."

Above all, he seems proud that he was able to do something, rather than what that something eventually went on to do: "Life can make you do many things, even kiss a man with a runny nose."

Xiaomi Corp founder Lei Jun (雷軍) on May 22 made a high-profile announcement, giving online viewers a sneak peek at the company’s first 3-nanometer mobile processor — the Xring O1 chip — and saying it is a breakthrough in China’s chip design history. Although Xiaomi might be capable of designing chips, it lacks the ability to manufacture them. No matter how beautifully planned the blueprints are, if they cannot be mass-produced, they are nothing more than drawings on paper. The truth is that China’s chipmaking efforts are still heavily reliant on the free world — particularly on Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing

Keelung Mayor George Hsieh (謝國樑) of the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) on Tuesday last week apologized over allegations that the former director of the city’s Civil Affairs Department had illegally accessed citizens’ data to assist the KMT in its campaign to recall Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) councilors. Given the public discontent with opposition lawmakers’ disruptive behavior in the legislature, passage of unconstitutional legislation and slashing of the central government’s budget, civic groups have launched a massive campaign to recall KMT lawmakers. The KMT has tried to fight back by initiating campaigns to recall DPP lawmakers, but the petition documents they

A recent scandal involving a high-school student from a private school in Taichung has reignited long-standing frustrations with Taiwan’s increasingly complex and high-pressure university admissions system. The student, who had successfully gained admission to several prestigious medical schools, shared their learning portfolio on social media — only for Internet sleuths to quickly uncover a falsified claim of receiving a “Best Debater” award. The fallout was swift and unforgiving. National Yang Ming Chiao Tung University and Taipei Medical University revoked the student’s admission on Wednesday. One day later, Chung Shan Medical University also announced it would cancel the student’s admission. China Medical

Construction of the Ma-anshan Nuclear Power Plant in Pingtung County’s Hengchun Township (恆春) started in 1978. It began commercial operations in 1984. Since then, it has experienced several accidents, radiation pollution and fires. It was finally decommissioned on May 17 after the operating license of its No. 2 reactor expired. However, a proposed referendum to be held on Aug. 23 on restarting the reactor is potentially bringing back those risks. Four reasons are listed for holding the referendum: First, the difficulty of meeting greenhouse gas reduction targets and the inefficiency of new energy sources such as photovoltaic and wind power. Second,