"We used to grow opium," says Asoupa, a Lisu farmer in northwest Thailand, "but now we only grow cabbages and corn and other crops. It's better. If we grow opium, we get in trouble and lose everything."

Asoupa represents the country's once-primary opium growers, the hill tribes of northwest Thailand -- the Lisu, Lahu, Akha, Mein and Hmong. Living in remote jungle villages, they practice slash-and-burn agriculture.

The Thai government, in cooperation with the US Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) and UN International Drug Control Program (UNDCP), combined aggressive eradication and interdiction with flexible, alternative crop programs to encourage poverty-ridden hill tribes to abandon opium in favor of legal "cash crops" including cabbages, tomatoes, mung beans, peaches, strawberries, and Arabica coffee.

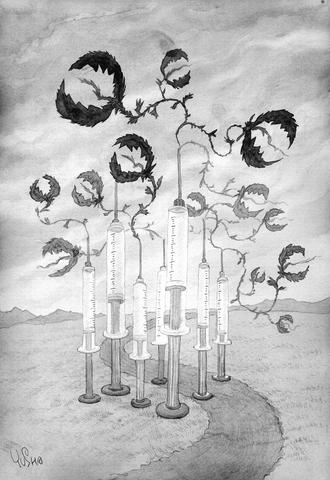

ILLUSTRATION: YU SHA

Thailand's official ban on opium cultivation began in 1959. The early alternative crop programs were plagued with problems, from insects to fluctuating market prices. The hill tribes couldn't compete with lowland farmers who got significantly better yields, and the lack of roads into tribal areas made it difficult to get crops to market.

The combination of improved market access, viable alternative crops, and harsh penalties encouraged most hill tribe villages to abandon opium. The alternative crop program in Thailand has been so successful that the UN was able to curtail direct support since most village economies now revolve around legal crops and are no longer in need of assistance.

The current opium crop, harvested during December and January, marks the fourth successive year the opium harvest in Thailand was estimated to be less than 1,000 hectares. By comparison, opium cultivation in Myanmar has ranged from 80,000 to 170,000 hectares.

While Thailand was initiating its eradication programs, Myanmar continued to produce up to 2,500 tonnes of opium annually. Much of it was refined into number four grade heroin, about 90 percent pure. To stifle the flow of drugs out of Burma, the Thai government organized Task Force 399. Comprised of several hundred military personnel and border guards, and supported by an extensive intelligence network, Task Force 399 snares drug smugglers as they enter Thailand. In an effort to circumvent the task force, some smugglers are traveling from Burma to Laos before attempting to enter Thailand.

Aggressive operations by the Border Patrol Police, Royal Thai Army Third Region Command and Task Force 399 finally caused many drug smugglers to avoid the country altogether and seek alternative routes out of Myanmar.

"A lot of heroin is being shipped through China," says William Snipes, the DEA's regional director in Bangkok.

"Part of it is feeding a growing addict population in China, but much of it is shipped on to Western markets," he said.

The UNDCP estimates that 60 percent of Myanmar's opiate production is now shipped through China.

To monitor drug traffickers, the US and the Thai government established three separate intelligence gathering modules. Each center collects information on drug activity and trafficking for its respective geographic region. Information is combined and analyzed to respond to immediate opportunities, feed ongoing investigations and predict future activity.

On the operational side, the DEA has four specially trained units that target specific operations and geographic areas of interest on land and sea. Thailand has the death penalty for drug smugglers and authorizes the forfeiture of criminal proceeds through the seizure of bank accounts and other assets. The Thai government has been very cooperative in fulfilling extradition requests of drug dealers for criminal prosecution in other countries.

While Thai authorities have been successful in eradicating the indigenous opium crop and intercepting heroin shipments coming from Myanmar, they have been plagued by a growing problem with amphetamine-type stimulants (ATS), primarily methamphetamine. Methamphetamine pills, called yaba in Thailand, have been around for decades.

Approximately 800 million methamphetamine pills were smuggled into Thailand during the last year. Virtually all of the production takes place in Myanmar and is smuggled across the border into Thailand, with some shipments being routed through Laos. The Wa and the Shan tribes are the primary players in the meth trade, just as they have been in the opium and heroin trade.

Initially used by truck drivers and workers to stay awake and increase stamina, usage among young Thais began increasing around 1988 as they copied the habits of dancers, a few locals, and tourists in Patpong and other entertainment areas. Ten years later, methamphetamine abuse was rampant, driven by increased supplies and falling prices. Methamphetamine indictments in Thailand increased from 1,025 in 1988 to a staggering 125,335 by 1998. There were 187,479 cases during 2001.

Eventually, methamphetamine made its way into schools, cutting across social and economic boundaries and the government declared it the number one security and social threat. The rise of methamphetamine also caused a surge in the number of polydrug users, individuals abusing more than one drug.

The volume of ecstasy entering Thailand began to increase about 1998, but its manufacture in the Netherlands kept its price steep and supply limited, a deterrent to Thai youth. The club scene, however, including raves frequented by Western tourists, has fueled recent growth of this ATS.

The seizure of ecstasy imported from Europe has increased more than six-fold in the last four years. Ecstasy is now being manufactured in Southeast Asia, lowering the price and increasing availability.

A sign of the growing drug problem and expanded efforts by Thai authorities is the number of Thais in jail.

"The prison population in Thailand has doubled in the last five years," says Douglas Rasmussen of the Bureau of International Narcotics and Law Enforcement (INL) at the US Embassy in Bangkok.

"Over 60 percent are for drug issues," Rasmussen said.

To combat the growing use of methamphetamines, Thai authorities, assisted by US government officials, significantly changed their approach to the drug trade. The Thai government broadened their scope from eradication and interdiction to demand reduction through education, prevention, and rehabilitation programs.

"The Thais are using a multifaceted approach to combat the drug trade," notes Rasmussen. "They realize you can't just go after the supply side, you have to go after the demand side too."

A number of agencies were established to provide training programs in drug counseling and drug prevention for school teachers and community outreach workers throughout Thailand. A joint effort by the DEA and Thai officials set up a successful DARE (Drug Abuse Resistance Education) program based on the US model.

"Approximately 130 Thai police officers conduct drug awareness classes in middle and high schools," says Snipes. "The Thais are very concerned about methamphetamine going down into the younger ages."

The government established community antidrug center throughout Thailand, including one in Klum Tay, a notorious Bangkok slum.

"We must educate the younger generation," says a Thai police official, "and this will carry on because they will educate their children."

Thai actors and musicians have become involved in the campaign.

The Ministry of Public Health dramatically increased the number of drug treatment centers, and today there are over 500, ranging from public and private hospitals to drug rehab clinics. Since methamphetamine treatment is different than heroin, and requires more family support, drug centers have modified and expanded their programs to address specific needs.

Since 1999, the majority of people seeking treatment in Thailand have been addicted to methamphetamines. As recently as 1995, heroin (90 percent) and opium (5 percent) addicts accounted for 95 percent of the treatment population.

To help fight drugs on a regional level, the International Law Enforcement Academy (ILEA) of Bangkok opened in 1999 under the direction of the US State Department's Bureau of International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs (INL). The curriculum covers everything from narcotics trafficking and money laundering to computer crime and illegal migration.

Courses are taught by the Thai police and the Office of Narcotics Control Board in conjunction with representatives of several US government agencies. Experts are brought in from around the world including the Netherlands, Australia and Taiwan.

Police and government officials from Thailand, Cambodia, China, Laos, Vietnam, Singapore, Malaysia, Indonesia, Brunei and the Philippines attend the academy.

"One of our objectives," says Luis Diaz-Rodriquez with INL, "is to build cooperation between branches of law enforcement, both within and between these countries. We hope to have alumni that will assist each other in investigations and exchange information between themselves and their US counterparts."

In addition to the ILEA, the UN Drug Control Office in Bangkok has developed a Regional Cooperation Program with Thailand, Cambodia, China, Laos, Myanmar and Vietnam.

"The regional program complements a number of different country level projects," says Vincent McClean, formerly with the UNDCP Bangkok office.

"It also encourages cooperation between members by bringing them together for joint training and discussion," he said.

McClean is currently the director of the UN Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) in New York.

The proliferation of new drugs like methamphetamine and ecstasy, combined with the devastating impact of heroin, cocaine and other narcotics, can best be controlled through interagency cooperation at the regional and global level.

At one time, many transit countries, that is countries through which drugs were transported on their way to more lucrative markets, didn't consider the drug trade to be a serious problem. That changed when the "bleed" effect -- drugs dealt along transit routes -- caused them to have a growing population of addicts and the secondary problems of crime, HIV and corruption of police officers and public officials.

Developing interagency operations like those run by the UN, DEA and INL facilitates regional cooperation. These programs provide education and incentive to discourage people from using drugs, help for those already addicted and a flexible, cooperative web of law enforcement and regulatory agencies that apprehend drug dealers and eliminate smuggling operations.

James Emery is an anthropologist and journalist who has covered the Asian drug trade for over 15 years.

Speaking at the Copenhagen Democracy Summit on May 13, former president Tsai Ing-wen (蔡英文) said that democracies must remain united and that “Taiwan’s security is essential to regional stability and to defending democratic values amid mounting authoritarianism.” Earlier that day, Tsai had met with a group of Danish parliamentarians led by Danish Parliament Speaker Pia Kjaersgaard, who has visited Taiwan many times, most recently in November last year, when she met with President William Lai (賴清德) at the Presidential Office. Kjaersgaard had told Lai: “I can assure you that ... you can count on us. You can count on our support

Denmark has consistently defended Greenland in light of US President Donald Trump’s interests and has provided unwavering support to Ukraine during its war with Russia. Denmark can be proud of its clear support for peoples’ democratic right to determine their own future. However, this democratic ideal completely falls apart when it comes to Taiwan — and it raises important questions about Denmark’s commitment to supporting democracies. Taiwan lives under daily military threats from China, which seeks to take over Taiwan, by force if necessary — an annexation that only a very small minority in Taiwan supports. Denmark has given China a

Many local news media over the past week have reported on Internet personality Holger Chen’s (陳之漢) first visit to China between Tuesday last week and yesterday, as remarks he made during a live stream have sparked wide discussions and strong criticism across the Taiwan Strait. Chen, better known as Kuan Chang (館長), is a former gang member turned fitness celebrity and businessman. He is known for his live streams, which are full of foul-mouthed and hypermasculine commentary. He had previously spoken out against the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and criticized Taiwanese who “enjoy the freedom in Taiwan, but want China’s money”

A high-school student surnamed Yang (楊) gained admissions to several prestigious medical schools recently. However, when Yang shared his “learning portfolio” on social media, he was caught exaggerating and even falsifying content, and his admissions were revoked. Now he has to take the “advanced subjects test” scheduled for next month. With his outstanding performance in the general scholastic ability test (GSAT), Yang successfully gained admissions to five prestigious medical schools. However, his university dreams have now been frustrated by the “flaws” in his learning portfolio. This is a wake-up call not only for students, but also teachers. Yang did make a big