Talk about corruption in developing countries -- and in some developed ones -- is running rampant. In the past, corruption was usually said to be located within the ranks of public servants, and this was used as a partial justification for privatization, especially in developing countries.

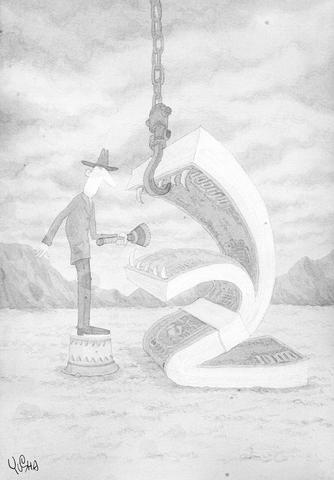

Cheerleaders of the private sector, however, failed to reckon with the ability of company bosses to indulge in corrupt practices on an almost unfathomable scale, something American corporate capitalism has demonstrated amply of late. Corrupt bosses put to shame petty government bureaucrats who steal a measly few thousand dollars -- even a few million. The scale of theft achieved by those who ransacked Enron, Worldcom, and other corporations is in the billions of dollars, greater than the GDP of many countries.

My research over the past thirty years focused on the economics of information. With perfect information -- an assumption made by traditional economics, though one not fully appreciated by free market advocates -- these problems would never have occurred. Shareholders would instantly realize that the books were cooked, and roundly punish the offending company's share price.

But information is never perfect. Because of tax advantages and inappropriate accounting practices firms richly rewarded executives with stock options. With these in hand, company bosses could ensure that they were well paid without doing anything to benefit their company's bottom line.

All they needed to do was boost the stock price, then cash in their option. It was a system almost too good to be true: while executives received millions in compensation, no one seemed to be bearing the cost.

Of course, this was a mirage: by issuing such options shareholder value was diluted. Moreover, this was worse than dishonest: stock options provided managers with strong incentives to get the value of their stocks up fast. What mattered was not a company's long-term strength but its short-term appearance.

Corporate officers respond to incentives and opportunities. Over the last decade-and-a-half, executive compensation in America soared. So, too, did the fraction of that compensation that is tied to a company's stock price, to the point where the fraction related to long-term performance is quite small. It was as if managers were actively discouraged from looking at fundamentals.

The proponents of markets are right that incentives matter, but inappropriate incentives do not create real wealth in the economy, only a massive misallocation of resources of the sort we see now in such industries as telecoms. Overinflated prices lead firms to overinvest.

As research over the past three decades demonstrates, when information is imperfect -- as it always is! -- Adam Smith's invisible hand, by which the price system is supposed to guide the economy to efficient outcomes, is invisible in part because it is absent. With the wrong incentives, with the kinds of incentives that were in place in corporate America, a drive for the creation of the appearance of wealth took hold, at the cost of actual wealth.

By the same token, auditing firms that make more money from consulting than from providing auditing services have a conflict of interest: they have (at least in the short run) an incentive to go easy on their clients, or even, as consultants, to help their clients think of ways -- "within the rules," of course -- that improve the appearance of profits.

Or analysts at investment banks that earn large fees from stock offerings may -- as we have seen not so long ago -- tout stocks even when they are dubious about them. If these banks also have a commercial bank division, they may have an incentive to maintain credit lines beyond a prudent level, because to cut such lines would put at risk high potential future revenues from mergers and acquisitions and stock and bond issues.

Moreover, a distortion of private incentives affects public incentives as well, and the two become intertwined. As "money talks" in politics, private incentives distort public policy and prevent it from correcting market failures in ways that, in turn, further distort private incentives. America's Securities and Exchange Commission's head recognized the problems posed by conflicts of interests in accounting, but his efforts to put in place rules to address the problem met with overwhelming resistance from the industry -- until the scandals made change irresistible. Similarly, the accounting problems with executive stock options were recognized by the Financial Accounting Standards Board, but again early efforts at reform met with resistance, from the obvious sources. Here, political pressure, including from the US Treasury, was put on the supposedly independent board not to make the change. These problems arise at both the national and international levels.

Some countries try to fight against this vicious circle. For example, because we rightly suspect government officials who move too quickly into private sector jobs related to their public roles, many democracies have rules against such "revolving doors." To be sure, there are costs in imposing such restrictions -- they may, for example, deter qualified individuals from accepting public employment -- and the restrictions seldom eliminate conflicts of interest altogether.

But restrictions of this kind -- affecting both private and public sectors -- are often necessary because of imperfect information: we cannot really be sure what motivates an individual, even if the individual seems of the highest integrity. The loss of public confidence that may result from not acting may be even higher than the cost of governmental regulation -- indeed, this loss recently resulted in billions of dollars of reductions in the value of shares.

Conflicts of interest will never be eliminated, either in the public or private sector. But by making ourselves more sensitive to their presence and becoming aware of the distorted incentives to which they give rise, as well as by imposing regulations that limit their scope and increasing the amount of required disclosure, we can mitigate their consequences, both in the public and the private sector.

Joseph E. Stiglitz is professor of economics and finance at Columbia University, the winner of the 2001 Nobel Prize in economics, and author of Globalization and its Discontents. Copyright: Project Syndicate

In their recent op-ed “Trump Should Rein In Taiwan” in Foreign Policy magazine, Christopher Chivvis and Stephen Wertheim argued that the US should pressure President William Lai (賴清德) to “tone it down” to de-escalate tensions in the Taiwan Strait — as if Taiwan’s words are more of a threat to peace than Beijing’s actions. It is an old argument dressed up in new concern: that Washington must rein in Taipei to avoid war. However, this narrative gets it backward. Taiwan is not the problem; China is. Calls for a so-called “grand bargain” with Beijing — where the US pressures Taiwan into concessions

The term “assassin’s mace” originates from Chinese folklore, describing a concealed weapon used by a weaker hero to defeat a stronger adversary with an unexpected strike. In more general military parlance, the concept refers to an asymmetric capability that targets a critical vulnerability of an adversary. China has found its modern equivalent of the assassin’s mace with its high-altitude electromagnetic pulse (HEMP) weapons, which are nuclear warheads detonated at a high altitude, emitting intense electromagnetic radiation capable of disabling and destroying electronics. An assassin’s mace weapon possesses two essential characteristics: strategic surprise and the ability to neutralize a core dependency.

Chinese President and Chinese Communist Party (CCP) Chairman Xi Jinping (習近平) said in a politburo speech late last month that his party must protect the “bottom line” to prevent systemic threats. The tone of his address was grave, revealing deep anxieties about China’s current state of affairs. Essentially, what he worries most about is systemic threats to China’s normal development as a country. The US-China trade war has turned white hot: China’s export orders have plummeted, Chinese firms and enterprises are shutting up shop, and local debt risks are mounting daily, causing China’s economy to flag externally and hemorrhage internally. China’s

During the “426 rally” organized by the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and the Taiwan People’s Party under the slogan “fight green communism, resist dictatorship,” leaders from the two opposition parties framed it as a battle against an allegedly authoritarian administration led by President William Lai (賴清德). While criticism of the government can be a healthy expression of a vibrant, pluralistic society, and protests are quite common in Taiwan, the discourse of the 426 rally nonetheless betrayed troubling signs of collective amnesia. Specifically, the KMT, which imposed 38 years of martial law in Taiwan from 1949 to 1987, has never fully faced its