US President George W. Bush's new strategic doctrine says that while the US will seek to enlist the support of the international community for its policies, America will not hesitate to act alone if necessary to exercise its right of self defense. Many of America's allies say that they resent the excessive unilateralism of the Bush administration's foreign policy, but even former US president Bill Clinton argued that the US must be prepared to go it alone when no alternative exists. So the debate about unilateralism vs. multilateralism has been greatly oversimplified.

International rules bind the US and limit its freedom of action, but they also serve US interests by binding others to observable rules and norms as well. Moreover, opportunities for foreigners to raise their voice and influence US policies constitute an important incentive for being part of an alliance with the US. America's membership in a web of multilateral institutions ranging from the UN to NATO may reduce US autonomy, but seen in the light of a constitutional bargain, the multilateral ingredient of the US' current preeminence is a key to its longevity, because it reduces the incentives for constructing alliances against the US.

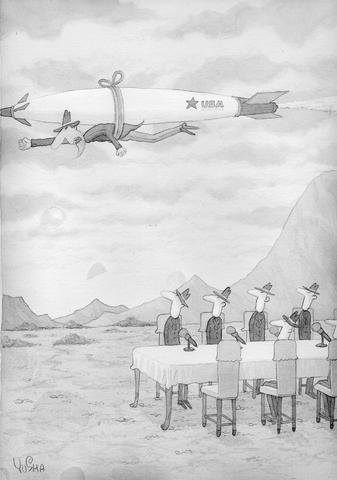

ILLUSTRATION: YU SHA

Multilateralism, however, is a matter of degree, and not all multilateral arrangements are good. Like other countries, US should occasionally use unilateral tactics. So how to choose when and where?

No country can rule out unilateral action in cases that involve its very survival. Self-defense is permitted under Article 51 of the UN Charter, and pre-emptive self-defense may be necessary when a terrorist organization presents a strong or imminent threat. Bush's military action in Afghanistan was largely unilateral, but was carried out against a backdrop of support from NATO allies and UN resolutions.

Even when survival is not at stake, unilateral tactics sometimes induce others to make compromises that advance multilateral interests. During the Ronald Reagan administration, trade legislation that threatened unilateral sanctions if others did not negotiate helped create the conditions that prodded other countries to move forward with the creation of the WTO and its dispute settlements mechanism.

Some multilateral initiatives also are recipes for inaction, or are contrary to American values. For example, the "New International Information Order" proposed by UNESCO in the 1970s would have helped authoritarian governments restrict freedom of the press. More recently, Russia and China prevented UN Security Council authorization of intervention to stop human-rights violations in Kosovo in 1999. Ultimately the US decided to go ahead without Security Council approval. Even then US intervention was not unilateral, but taken with the strong support of NATO allies.

However, some transnational issues are inherently multilateral and cannot be managed without the help of other countries. Climate change is a perfect example. The US is the largest source of greenhouse gases, but three quarters of the sources originate outside its borders. Without cooperation, the problem is beyond US control. The same is true of a long list of items: the spread of infectious diseases, the stability of global financial markets, the international trade system, the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction, narcotics trafficking, international crime syndicates and transnational terrorism.

Multilateralism is a mechanism to get other countries to share the burden of providing public goods. Sharing also helps foster commitment to common values. Even militarily, the US should rarely intervene alone. Not only does this comport with the preferences of the US public -- polls show that two-thirds of Americans prefer multilateral actions to unilateral ones -- but it has practical implications as well. The US pays a minority share of UN and NATO peacekeeping operations, and the legitimacy of a multilateral umbrella reduces collateral political costs to America's so-called "soft" or attractive power -- ie, its aid and cultural initiatives.

Finally, in choosing between multilateral and unilateral tactics, Americans must consider the effects of the decision on its soft power, which can be destroyed by excessive unilateralism and arrogance. In deciding whether to use multilateral or unilateral tactics, or to adhere or refuse to go along with particular multilateral initiatives, any country must consider how to explain its actions to others and what the effects will be on its soft power.

US foreign policy should have a general preference for multilateralism, but not all forms multilateralism. At times, the US will have to go it alone. When the US does so in pursuit of public goods that benefit others as well as Americans, the nature of its ends may substitute for the means in making US power acceptable in the eyes of others.

If the US first makes an effort to consult others and try a multilateral approach, its occasional unilateral tactics are more likely to be forgiven. But if it succumbs to the unilateralist temptation too easily, it is likely to encounter the criticisms that the Bush administration is now encountering. In such cases, the likelihood of failure increases, because of the intrinsically multilateral nature of transnational issues in a global age and the costly effects on US soft power that unaccepted unilateral actions may impose. Even a solitary superpower should follow this rule of thumb: try multilateralism first.

Joseph Nye is dean of Harvard's Kennedy School of Government and author of The Paradox of American Power: Why the World's Only Superpower Can't Go It Alone. He is a former US assistant secretary of defense and former director of the US National Security Agency.

Copyright: Project Syndicate

China has not been a top-tier issue for much of the second Trump administration. Instead, Trump has focused considerable energy on Ukraine, Israel, Iran, and defending America’s borders. At home, Trump has been busy passing an overhaul to America’s tax system, deporting unlawful immigrants, and targeting his political enemies. More recently, he has been consumed by the fallout of a political scandal involving his past relationship with a disgraced sex offender. When the administration has focused on China, there has not been a consistent throughline in its approach or its public statements. This lack of overarching narrative likely reflects a combination

US President Donald Trump’s alleged request that Taiwanese President William Lai (賴清德) not stop in New York while traveling to three of Taiwan’s diplomatic allies, after his administration also rescheduled a visit to Washington by the minister of national defense, sets an unwise precedent and risks locking the US into a trajectory of either direct conflict with the People’s Republic of China (PRC) or capitulation to it over Taiwan. Taiwanese authorities have said that no plans to request a stopover in the US had been submitted to Washington, but Trump shared a direct call with Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平)

Heavy rains over the past week have overwhelmed southern and central Taiwan, with flooding, landslides, road closures, damage to property and the evacuations of thousands of people. Schools and offices were closed in some areas due to the deluge throughout the week. The heavy downpours brought by the southwest monsoon are a second blow to a region still recovering from last month’s Typhoon Danas. Strong winds and significant rain from the storm inflicted more than NT$2.6 billion (US$86.6 million) in agricultural losses, and damaged more than 23,000 roofs and a record high of nearly 2,500 utility poles, causing power outages. As

The greatest pressure Taiwan has faced in negotiations stems from its continuously growing trade surplus with the US. Taiwan’s trade surplus with the US reached an unprecedented high last year, surging by 54.6 percent from the previous year and placing it among the top six countries with which the US has a trade deficit. The figures became Washington’s primary reason for adopting its firm stance and demanding substantial concessions from Taipei, which put Taiwan at somewhat of a disadvantage at the negotiating table. Taiwan’s most crucial bargaining chip is undoubtedly its key position in the global semiconductor supply chain, which led