Robert Mugabe is an aging tyrant who is single-handedly destroying Zimbabwe's economy and social stability. Like many other tyrants, he seems ready to do anything to extend his 22 years in power, including resorting to violence and rigging elections. His corrupt cronies and military officials who benefitted during his lawless regime stand by him -- not only to preserve their own corrupt incomes, but also out of fear of the retribution that might follow their fall from power. Despite protests from the US and Europe about his thuggery, Mugabe has so far had his way.

Tyranny is of course one of the oldest political stories. But in an interconnected world, isn't it possible for the international community to do more to restrain tyrants in order to ensure a more stable global environment? A tricky question, no doubt. No country is ready to cede political sovereignty to outside powers or electoral monitors. Yet the high costs of tyranny spill over to the rest of the world, in the forms of uncontrolled disease, refugee movements, violence and criminality. The world has a stake in preventing the continued misrule of Mugabe and others like him.

One plausible idea is regional monitoring -- that a country's neighbors would help forestall such tyranny. This is plausible, since neighbors are the biggest direct losers when instability spills across borders. Yet neighbors are also the most fearful of challenging one of their own. So far, the Southern African Development Community (SADC) has been acquiescent in the face of Mugabe's abuses. If that silence continues, it will gravely undermine SADC institutions, and will cast a deep pall over the most important leader in SADC, South Africa's President Thabo Mbeki.

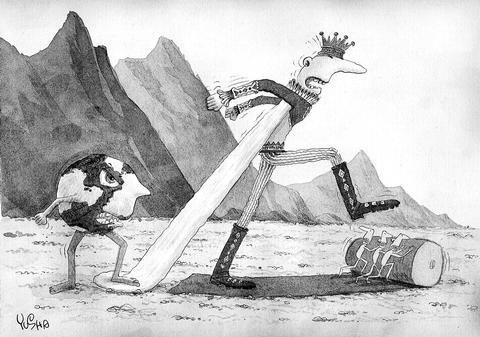

ILLUSTRATION: YU SHA

Sanctions offer another approach. The US, Europe and other democracies should not continue to do "business as usual" with Zimbabwe. Mugabe and his henchmen have stashed millions of dollars abroad in the past year according to plausible press accounts. These accounts should be frozen, despite the difficulty of doing so in a world rife with secret banking and nominee accounts that disguise true ownership. Mugabe's phony elections, moreover, should go unrecognized, and Mugabe denied a welcome as a legitimate head of state in international gatherings.

Sanctions, however, are clumsy, costly and often ineffective. They are insufficient to stop abuses (after all, sanctions were threatened before the elections) and risk pushing Zimbabwe's economy deeper into crisis, hurting millions of innocent people, especially during a period of intensifying hunger and drought. Sanctions are also unlikely to secure wide acclamation. Africans will no doubt feel that their continent is being singled out unfairly when such abuses exist throughout the world.

An alternative approach, giving positive inducements to a tyrant to leave office, might work in some circumstances. Some long-time leaders have been coaxed from office through blandishments, high-profile international positions, or even amnesties and comfortable exiles in safe locations.

A more general -- perhaps more powerful -- approach is for the international community to agree on general, enforceable political standards. One such standard, which might conceivably win international consent, would be an "international term limit" on heads of government. The world community would agree that no individual should serve as the head of government (president, prime minister, or other equivalent position) for more than "X" years. International agencies such as the World Bank and the IMF would automatically stop making loans to countries where the head of government exceeds that limit.

Many countries already have such limits. In the US, presidents are limited to two terms in office. In other countries, there is a single presidential term, usually of 5 to 8 years. The world as a whole might agree on a weaker, but globally acceptable minimum standard, say a term limit of no more than 20 years. Any head of government who stays in power for more than two decades would automatically lose international recognition.

Even non-democracies such as modernized China could accept this rule, because it would apply to heads of government, not ruling parties. China routinely rotates the highest executive positions, as it realizes that a change of power prevents tyrants from gaining excessive power, a lesson learned painfully during Mao Zedong (毛澤東)'s long and often disastrous reign. Corruption is limited by the frequent alternation of power, since tyrants typically need many years to build up systems of mega-corruption, usually involving family and business associates.

An international term limit, of course, could infringe on the right of a real democracy to keep a popular leader for more than 20 years. Some parliamentary leaders of Western democracies have approached this limit, such as Helmut Kohl and his 16 years in office in Germany. But even in strong democracies, the final years of a long rule are typically the worst. Kohl's last years, for example, were marked by electoral corruption. Given the incredible advantages that incumbents have over challengers in nearly every political system, a firm time limit would strengthen even the strongest of existing democracies.

An international term limit would have put Zimbabwe on notice early on: Mugabe's continued rule after 22 years would be tantamount to international isolation. Mugabe's challengers would have been given the upper hand in the political conflict, and it might have been taken for granted inside Zimbabwe and the SADC that Mugabe would not and should not contest this round of elections.

In looking at the roster of long-serving heads of government in the second half of the 20th century -- such as Mao, Joseph Stalin, Francisco Franco, Kim Il-sung and Nicolae Ceausescu -- it is clear that an enforced international term limit would have spared the world considerable grief and turmoil. In our much more democratic and interconnected world, it is possible that a clear international norm limiting time in power could spare the world from dictatorship and destabilization in the future.

Jeffrey D. Sachs is Galen L. Stone Professor of Economics and director of the Center for International Development, Harvard University.t: copyright: Project Syndicate

In their recent op-ed “Trump Should Rein In Taiwan” in Foreign Policy magazine, Christopher Chivvis and Stephen Wertheim argued that the US should pressure President William Lai (賴清德) to “tone it down” to de-escalate tensions in the Taiwan Strait — as if Taiwan’s words are more of a threat to peace than Beijing’s actions. It is an old argument dressed up in new concern: that Washington must rein in Taipei to avoid war. However, this narrative gets it backward. Taiwan is not the problem; China is. Calls for a so-called “grand bargain” with Beijing — where the US pressures Taiwan into concessions

The term “assassin’s mace” originates from Chinese folklore, describing a concealed weapon used by a weaker hero to defeat a stronger adversary with an unexpected strike. In more general military parlance, the concept refers to an asymmetric capability that targets a critical vulnerability of an adversary. China has found its modern equivalent of the assassin’s mace with its high-altitude electromagnetic pulse (HEMP) weapons, which are nuclear warheads detonated at a high altitude, emitting intense electromagnetic radiation capable of disabling and destroying electronics. An assassin’s mace weapon possesses two essential characteristics: strategic surprise and the ability to neutralize a core dependency.

Chinese President and Chinese Communist Party (CCP) Chairman Xi Jinping (習近平) said in a politburo speech late last month that his party must protect the “bottom line” to prevent systemic threats. The tone of his address was grave, revealing deep anxieties about China’s current state of affairs. Essentially, what he worries most about is systemic threats to China’s normal development as a country. The US-China trade war has turned white hot: China’s export orders have plummeted, Chinese firms and enterprises are shutting up shop, and local debt risks are mounting daily, causing China’s economy to flag externally and hemorrhage internally. China’s

During the “426 rally” organized by the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and the Taiwan People’s Party under the slogan “fight green communism, resist dictatorship,” leaders from the two opposition parties framed it as a battle against an allegedly authoritarian administration led by President William Lai (賴清德). While criticism of the government can be a healthy expression of a vibrant, pluralistic society, and protests are quite common in Taiwan, the discourse of the 426 rally nonetheless betrayed troubling signs of collective amnesia. Specifically, the KMT, which imposed 38 years of martial law in Taiwan from 1949 to 1987, has never fully faced its