President George W. Bush made it clear in his inaugural address that the US would rebuild strong political and security relationships with its allies.

Echoing a theme from the second presidential debate, President Bush said that "America remains engaged in the world, by history and by choice, shaping a balance of power that favors freedom ... we will defend our allies and our interests."

This important statement of resolve is going to echo in the halls of the Pentagon, where Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld is committed to strengthening the US alliance with Japan, missile defenses for US allies, and engaging in cooperative research projects to improve mutual security.

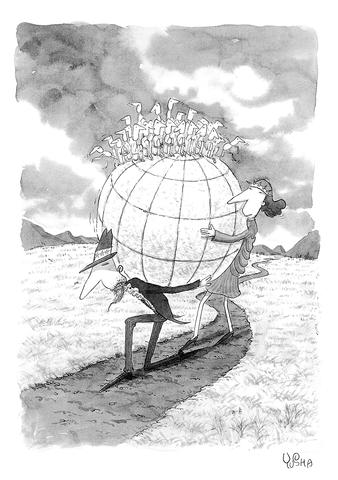

By Yu Sha

Secretary of State Colin Powell, in his confirmation hearing on Jan. 17, 2001, as did President Bush, made it clear that the US' alliances in Asia, "particularly Japan," are the bedrock of security in the Asia-Pacific region.

In defining the foreign policy priorities for the Bush Administration, Colin Powell made it clear that China is not a "strategic partner."

This is a significant departure from the policies of the Clinton administration. Powell noted that there are areas where China and the US have common interests, and other areas where China is a potential rival of the US. He emphasized that the US will trade with China, and so will Japan.

China's threats of military force against Taiwan, however, will make some decisions difficult. The US will work hard, through carefully crafted legislation and export regulations, to make sure that trade does not improve China's military capabilities. And the US will expect its friends and allies to be equally careful in their decisions regarding trade with China that involves high technology goods or manufacturing processes with military application. International security related decisions were never simple, even during the cold war.

A group of countries with shared ideals, a belief in democracy, economic freedom, market economies and unfettered trade, agreed to work together to prevent the communist block from imposing its will over their populations.

These counties formed alliances designed to protect each other from aggression.

The threat, then, was obvious, and to prevent the communist bloc from gaining the upper hand in military capabilities, the allies formed an organization designed to provide for prudent national security controls on the trade of certain technologies and equipment that could be used for threatening military purposes.

To a large extent that organization, the Coordinating Committee for Multilateral Export Controls, or COCOM, as it was known, was reasonably successful. Access to critical defense technologies developed in the free world, for the most part, was denied to the Soviet Union, China, and the Warsaw Pact countries.

Today, however, it is difficult to achieve consensus on global threats to security. Many nations (and even non-state actors that function in the international arena) may develop or export weapons or technologies that are threatening to some nations, but not to others, or upset the delicate security balance in a geographic region. Thus, in the world of global enterprise and global industrial production, it is difficult to restrict the transfer of technology, goods or services on national security grounds.

Despite this difficulty, the US must work with its allies and friends to ensure that export decisions undertaken in one nation don't threaten the interests of another.

Protection

It will take patient consultation and discussion between allies to arrive at a common understanding of what technologies or industrial processes may require protection, and from what countries they must be withheld.

Each country will have its own commercial interests that may conflict, and commercial interests could conflict with security interests. Close consultation will be increasingly important for technology cooperation between Japan and the US. Consider, for instance, that the advanced materials processing, sensor and signal processing technologies that will go into any future ballistic missile defense system on which Japan and the US might cooperate will be quite sensitive. The US, and its Congress, which ultimately enacts the laws that place national security controls on US exports, will want some form of assurance that sensitive systems and technologies will be protected from disclosure, sale or transfer to other countries.

The first principle of limited government should be to support free trade and commerce without interfering in the decisions of private business. Nonetheless, there are sound reasons to exercise caution in export control policies when the sale of certain items or technologies could affect the balance of power in a region.

People who lived through the cold war will not forget the damage done to allied and NATO ability to track and detect Soviet ballistic missile and attack submarines when a Japanese company sold industrial milling equipment that enabled Soviet industry to manufacture propellers that were significantly quieter than Soviet industry would have been capable of without such a sale. The acquisition of this precision machinery forced the US and its allies to develop new ways to detect and locate the submarines.

China is acquiring a number of weapon and command and control systems that could extend the range of its own missiles and aircraft, and permit it to project power at greater ranges from its shores. In some cases, the assistance is coming from US allies, or from major recipients of financial aid from the US.

Israel is believed to have aided in the ongoing development of China's Jian-10 (F-10) fighter aircraft, which is expected to carry versions of Israeli missiles. The US intelligence community suspects that avionics components, advanced composite materials, and flight control specifications related to the abandoned Israeli Lavi aircraft program, and derived from the US F-16 aircraft were sold to China by Israeli Aircraft Industries. If this aircraft is eventually fielded by China it will give the People's Liberation Army (PLA) Air Force an indigenously produced modern fighter aircraft.

The Jian-10, as earlier model Chinese fighters, would carry missiles incorporating technology and assistance from such countries as France and Italy.

In 1999, Israeli Aircraft Industries was scheduled to conclude the sale of the Phalcon airborne early warning radar systems to China. The radar systems were to be fitted by Israel on Russian IL-76 (Candid) transport aircraft, providing China with a relatively advanced airborne early warning (AWACS) capability.

With these systems, China would have been better equipped to detect aircraft at a greater distance, and, more seriously, to coordinate the actions of numerous fighter aircraft in air combat. The AWACS radar, combined with other command and control and data exchange systems, would also have helped the PLA Air Force extend the range of its cruise missiles and air-to-air missiles.

Bowing to intense US diplomatic pressure, Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Barak cancelled the impending sale on July 13, 2000. Some members of the US Congress threatened to cut economic aid to Israel in retaliation for the radar sale to China because the acquisition of these particular systems had the potential to change the balance of power in the Asia-Pacific.

System acquisition

China will probably acquire a less capable system from Russia, also a major recipient of major American, and Japanese financial assistance.

In the case of the AWACS radar systems, the other country that sought to make the sale to China was Great Britain, perhaps the US' closest European ally. Such a system of command, control and early warning, and the high-tech weapons it directs, will certainly be used to deter attempts by the US to maintain the peace and stability of the western Pacific should China carry out its threats to use force against Taiwan.

The systems could also be used to affect the control of the islands and sea lines of communication in the South China or East China Seas.

While the transfer of British radar technology to China did not take place, China's acquisition of air-to-air refueling systems for combat aircraft has the potential to change the way that China can project power in East Asia and into the South China Sea.

These airborne refueling systems are being developed for the PLA Air Force with the assistance of one of America's strongest allies, Great Britain. An aerial refueling capability allows China's combat aircraft to operate for longer periods at extended ranges in such areas as the Senkaku Islands, areas off Japan and in the South China Sea.

None of the nations involved in these sales or exports, however, have military forces or vital interests in the Asia-Pacific region, but these exports have a direct effect on the US and its traditional friends and allies.

In a less dramatic, but no less important way, illegal trade can change the military balance in areas far away from the country acting as an entrepot. One simple case that illustrates the difficulty of these issues was recently outlined in The Washington Post on Dec. 9, 2000. Two men were arrested in California for attempting to ship American fighter aircraft parts to Iran in violation of the Arms Export Control Act of the US. According to the US Customs Service, "Singapore is a known trans-shipment point for items destined for Iran and other countries facing US trade sanctions."

Anyone who has visited Singapore knows how strictly that country is able to enforce its laws. One can be jailed for spitting on the street, chewing gum, or failing to flush a public toilet.

It is inconceivable that Singapore's security services cannot stop this illegal and dangerous trade. Yet it is also difficult for the US to take too strong a stance. Singapore permits US warships to dock and refuel there, allows a small permanent US military logistics presence to remain in its county, and permits US combat aircraft to fly through. It is a good friend to the US. But Singapore faces no security threat from Iran and the US does. Patient diplomacy is the way to address such differences among friends and allies.

The illegal transfer of parts or weapons, the export of which is restricted as munitions, like the transfer of sensitive technologies with military application, is of major concern to the US.

However, in the case related to Singapore, as described above, the entire regional security balance was not altered by the transaction. In the other cases involving allies, such as Great Britain, Israel, Italy and France, the balance of power in the Pacific could be altered by the systematic transfer of key technologies or weapon systems, with potential harm to US, and Japanese, security.

Strengthening ties

There are a number of ways that Japan and the US can strengthen their cooperation for the future. Consider some of the suggestions of former Assistant Secretaries of Defense Richard Armitage and Joseph Nye and their colleagues in the report of Oct. 11, 2000, The US and Japan: Advancing Toward a Mature Partnership, such as making US defense technology available to Japan, more robust joint military exercises, and true partnership in intelligence sharing.

Japan is now considering steps that would tighten its national security laws, establishing real penalties for revealing classified information or spying for another power. If the Diet approves these stronger security measures it will create conditions more conducive to increased defense cooperation.

Citizens of Japan must be confident that their elected officials are conducting the proper oversight of defense cooperation and intelligence activities, as suggested in the report, above. And when that happens, US industry and government will have more confidence to enter into real strategic partnerships with Japanese companies to develop cutting edge technology for defense.

Given the missile threat Japan faces, why shouldn't self-defense forces have some form of early warning satellite? Geo-stationary missile launch-detection satellites over Japan would detect launches from China, North Korea, and Russia. Such satellites could alert Japan's air defense and ballistic missile defense forces of a hostile launch, and, with data sharing, the information could also be utilized by the US.

More robust intelligence and defense cooperation between Japan and the US would strengthen the alliance and provide better protection for the citizens of both nations. And, with their combined diplomatic and economic strength and influence, Japan and the US could remind China's arms suppliers that the dangers. Japan does not have forces deployed all around the world like the US, therefore a global satellite system, the type the US needs, if probably not necessary for the defense of Japan. And a geo-stationary system designed for missile defense that is over Japanese territory could hardly be objectionable to any other country in Asia, or be taken as a threat. Moreover, the deployment and use of such a system for self-defense purposes would be consistent with article 9 of the Constitution. Should Japan eventually send self-defense forces outside the area on UN-related missions, the US and even NATO allies, could share their command and control systems as well as intelligence with Japan.

The main voice in Asia that objects to Japan defending itself is China. Chinese missile systems threaten all of Japan, including Okinawa.

Beijing's claims in the defense white papers in July 1998 and October 2000 that missile defense cooperation between the US and Japan constitutes an alliance that includes Taiwan are totally groundless.

Constitutional violation

The type of data-sharing between Japan and Taiwan that China claims might take place in its propaganda would be a violation of the Japanese constitution. Beijing knows this, but for its own purposes is trying to shift international opinion against self defense for Japan.

The final issue that must be considered when thinking about national security controls on exports is what cannot be controlled. The preceding paragraphs provided some thoughts on what manufacturing processes and technologies need to be carefully watched to protect the regional balance of security. But the globalization of manufacturing and the speed of technological change are moving much faster than any nation's export licensing system. Export controls should have reasonable provisions for national security, but they should not prevent companies from competing in the international market place.

It is probably impossible, or certainly counterproductive, to try to control telecommunications switching equipment and related mobile and Internet server technologies. Information technology is undergoing a revolution so fast, and is so important to the global economy, that attempts to control these technologies will only impede international commerce and limit national industry. Moreover, if one believes in free trade and the rapid exchange of ideas, the spread of these technologies, despite some military command and control applications, is desirable because it limits international isolation.

Another area where controls should probably be dropped is over computer processing speed. The speed at which chips operate is advancing so quickly that any attempts to regulate processing speed will probably never keep up with the speed of computer chip design. If these things may not be subject to controls, what related areas may be possible to put under control? Certain manufacturing processes that have primarily a military application, such as those dealing with weapons design or stealth technologies should be tightly controlled-this means that some advanced composite material manufacturing may not make it into the civilian market place quickly.

Also, certain computer related software, such as algorithms for weapons design or nuclear design will continue to require controls.

In conclusion, between the process of globalization in manufacturing and the commitment of more countries to lowering barriers to free trade, establishing and maintaining COCOM-like export controls on items and technologies with military and civilian application is increasingly difficult, perhaps impossible. However, careful consultation among allies with common security interests can ensure that there is a shared understanding of what needs control, and from what countries or companies certain manufacturing processes must be withheld. The consultation process necessarily will have to involve industry representatives, Such an approach will not be easy, but it will serve to strengthen understanding and cooperation among the allies and their major industrial corporations.

Larry Wortzel, PhD, is director of the Asian Studies Center at The Heritage Foundation. This article first appeared in Foresight Japan, Feb. 2001.

In their recent op-ed “Trump Should Rein In Taiwan” in Foreign Policy magazine, Christopher Chivvis and Stephen Wertheim argued that the US should pressure President William Lai (賴清德) to “tone it down” to de-escalate tensions in the Taiwan Strait — as if Taiwan’s words are more of a threat to peace than Beijing’s actions. It is an old argument dressed up in new concern: that Washington must rein in Taipei to avoid war. However, this narrative gets it backward. Taiwan is not the problem; China is. Calls for a so-called “grand bargain” with Beijing — where the US pressures Taiwan into concessions

The term “assassin’s mace” originates from Chinese folklore, describing a concealed weapon used by a weaker hero to defeat a stronger adversary with an unexpected strike. In more general military parlance, the concept refers to an asymmetric capability that targets a critical vulnerability of an adversary. China has found its modern equivalent of the assassin’s mace with its high-altitude electromagnetic pulse (HEMP) weapons, which are nuclear warheads detonated at a high altitude, emitting intense electromagnetic radiation capable of disabling and destroying electronics. An assassin’s mace weapon possesses two essential characteristics: strategic surprise and the ability to neutralize a core dependency.

Chinese President and Chinese Communist Party (CCP) Chairman Xi Jinping (習近平) said in a politburo speech late last month that his party must protect the “bottom line” to prevent systemic threats. The tone of his address was grave, revealing deep anxieties about China’s current state of affairs. Essentially, what he worries most about is systemic threats to China’s normal development as a country. The US-China trade war has turned white hot: China’s export orders have plummeted, Chinese firms and enterprises are shutting up shop, and local debt risks are mounting daily, causing China’s economy to flag externally and hemorrhage internally. China’s

During the “426 rally” organized by the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and the Taiwan People’s Party under the slogan “fight green communism, resist dictatorship,” leaders from the two opposition parties framed it as a battle against an allegedly authoritarian administration led by President William Lai (賴清德). While criticism of the government can be a healthy expression of a vibrant, pluralistic society, and protests are quite common in Taiwan, the discourse of the 426 rally nonetheless betrayed troubling signs of collective amnesia. Specifically, the KMT, which imposed 38 years of martial law in Taiwan from 1949 to 1987, has never fully faced its