Of the many commentaries on the summit meeting between US President George W. Bush and South Korean President Kim Dae-jung, I found most inspiring the comparison by Douglas Paal, one of the contenders for the ambassador's post in Seoul. "When it comes to strategies for dealing with North Korea, the American expert observed, US policy seems like that of a cop. Disarm the offender and get him off the street before he does any harm. For Kim Dae-jung, Paal continues, the approach is more like that of a priest: Understand and forgive the criminal, giving him time, space and resources to improve himself."

Interestingly, these sharp remarks were printed before the Washington summit. In the meantime, we could witness that, indeed, Bush and his associates argue like cops, or to use a kinder word, like policemen trained to protect as public order -- with the use of guns. On the other side of the spectrum stands the "priest." Kim Dae-jung has vowed to solve the problems of his divided nation peacefully. For his pledge and his uncompromising stance he has been awarded the highest of all international distinctions.

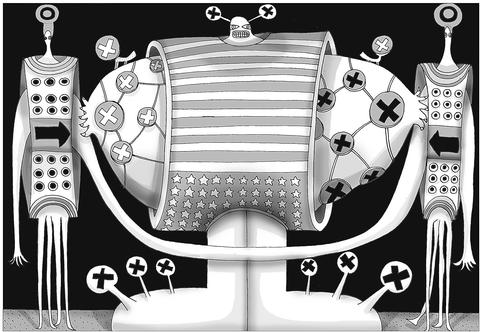

Illustration: Mountain People

The cop-priest dichotomy has more than one dimension: Kim and Bush seem to disagree about the respective roles diplomacy and the military should play in solving international conflicts. Seoul and Washington are also miles apart in their evaluation of the situation in North Korea. While Kim Dae-jung went out of his way to portray the North Korean leader as a politician eager to listen and prepared for change, the Americans bashed the "Dear Leader" with a myriad of all but diplomatic epithets. Secretary of State Colin Powell who, in the early part of the Kim Dae-jung visit, sounded almost conciliatory, ended up lashing out at the North Koreans: "It is a regime that is despotic, it is broken. We have no illusions about this regime. We have no illusions about the nature of the gentleman who runs North Korea. He is a despot," the secretary said during his testimony before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, that coincided with the South Korean presidential visit. This is not the rhetoric of a diplomat, who intends to enter into a political dialogue of any sorts with the government in Pyongyang in the near future. This is the rhetoric of a politician who wishes to satisfy the expectations of a conservative clientele.

The obvious gap in perception of North Korea between Seoul and Washington is important as the strategy of dealing with Pyongyang is determined. It has once more become clear that the government in Seoul has a clear-cut strategy in dealing with North Korea, while the American government lacks one. Seen from Seoul's angle, Kim's visit had a brilliant beginning , first the harmonious tete-a-tete with Secretary Powell, followed by the joint statement issued after the two presidents met. All the South Korean wishes seemed to have come true, but then -- like shooting from the hip -- the hosts reversed their rhetoric. The difference in language prompted one prominent Korean political scientist to speak of "a disaster for American diplomacy. Washington's seesaw-rhetoric has made it difficult to evaluate where the Americans stand. It also opened the door to rather conflicting evaluations of the summit: Was it a success, as the Seoul government stresses, or was it a failure, as the opposition believes? Kim's government has several arguments on her side, and refers to the joint statement which, without the slightest reservation endorses Seoul's sunshine policy, also confirming "President Kim's leading role in resolving inter-Korean issues." This document should be kept in mind, after the more belligerent statements during the latter part of the visit created the impression of serious discord between Seoul and Washington.

A bone of contention between Seoul and Washington ever since the Republicans came to power has been the issue of reciprocity. In a well-calculated move Kim Dae-jung brought up this issue himself, going on to the offensive about a matter his foes call the Achilles' heel of the Sunshine policy. In his meeting with Bush, and in a session with US Korea experts, Kim elucidated his concept of what has been termed "comprehensive reciprocity." Interestingly, some media rushed to call this concept a new idea. The South Korean opposition even went so far to claim a political victory: "We welcome the news, that president Kim, though belatedly, was awakened to the necessity of reciprocity in dealing with North Korea," a spokesman of the Grand National Party said.

It is worthwhile to take a closer look at what Kim presented to his American audience: The approach calls for the US and South Korea to provide economic and security assurances to North Korea in exchange for the North scrapping its weapons programs. In a tit-for-tat Seoul and Washington would seek three commitments from Pyongyang: adherence to the Framework Agreement of 1994, ending development and exports of ballistic missiles, and third -- a promise not to engage in any form of aggression against the South. In return -- Kim Dae-jung said -- "We will give three things to North Korea: One is for South Korea and the US to give the North assurances of its security. Second would be an appropriate level of economic assistance to the North. And third would be assistance so that North Korea can become a responsible member of the international community, so that it can get loans from the various international financial organisations."

Students of the more recent history of inner-Korean relations know there is nothing novel about this proposal. In more or less identical wording Kim presented the project of a comprehensive and reciprocal solution for the Korean question one year ago in his historical speech at the Free University in Berlin. There the South Korean president said, his government aimed at "a comprehensive settlement of all major pending issues based on a give-and-take principle of reciprocity." This has been South Korean policy vis-a-vis North Korea ever since.

Kim went to the US hoping for endorsement of his policy by his country's main ally. Instead, Kim encountered an administration, obviously still in the process of sorting out the files of its predecessors, making it clear it is in no rush. "We must not lose this opportunity," the Korean said. To no avail, it seems. In the long run the cop in Washington may slow down inner-Korean rapprochement, but I hope he is wise enough not to kill the priest's plans.

Dr Ronald Meinardus is the resident representative of the Freidrich-Nauman Foundation in Seoul

In their recent op-ed “Trump Should Rein In Taiwan” in Foreign Policy magazine, Christopher Chivvis and Stephen Wertheim argued that the US should pressure President William Lai (賴清德) to “tone it down” to de-escalate tensions in the Taiwan Strait — as if Taiwan’s words are more of a threat to peace than Beijing’s actions. It is an old argument dressed up in new concern: that Washington must rein in Taipei to avoid war. However, this narrative gets it backward. Taiwan is not the problem; China is. Calls for a so-called “grand bargain” with Beijing — where the US pressures Taiwan into concessions

The term “assassin’s mace” originates from Chinese folklore, describing a concealed weapon used by a weaker hero to defeat a stronger adversary with an unexpected strike. In more general military parlance, the concept refers to an asymmetric capability that targets a critical vulnerability of an adversary. China has found its modern equivalent of the assassin’s mace with its high-altitude electromagnetic pulse (HEMP) weapons, which are nuclear warheads detonated at a high altitude, emitting intense electromagnetic radiation capable of disabling and destroying electronics. An assassin’s mace weapon possesses two essential characteristics: strategic surprise and the ability to neutralize a core dependency.

Chinese President and Chinese Communist Party (CCP) Chairman Xi Jinping (習近平) said in a politburo speech late last month that his party must protect the “bottom line” to prevent systemic threats. The tone of his address was grave, revealing deep anxieties about China’s current state of affairs. Essentially, what he worries most about is systemic threats to China’s normal development as a country. The US-China trade war has turned white hot: China’s export orders have plummeted, Chinese firms and enterprises are shutting up shop, and local debt risks are mounting daily, causing China’s economy to flag externally and hemorrhage internally. China’s

During the “426 rally” organized by the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and the Taiwan People’s Party under the slogan “fight green communism, resist dictatorship,” leaders from the two opposition parties framed it as a battle against an allegedly authoritarian administration led by President William Lai (賴清德). While criticism of the government can be a healthy expression of a vibrant, pluralistic society, and protests are quite common in Taiwan, the discourse of the 426 rally nonetheless betrayed troubling signs of collective amnesia. Specifically, the KMT, which imposed 38 years of martial law in Taiwan from 1949 to 1987, has never fully faced its