For Japan, the Clinton era was eight years of Wall Street financiers such as Bob Rubin and academics such as Larry Summers criticizing Japan's economic policy, trade lawyers like Mickey Kantor and Charlene Barshefsky harping about opening the Japanese market and China experts dominating US foreign policy toward Asia.

The advent of the Bush administration promises a refreshing reprieve from Japan-bashing and the reassertion of the primacy of the US-Japan security relationship in the region.

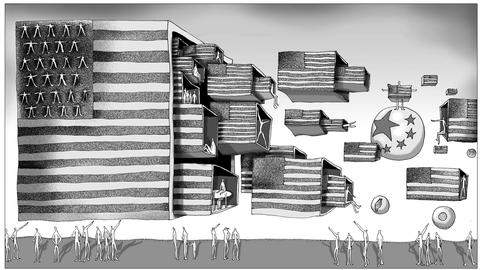

Illustration: Mountain People

Both policies should be music to most Japanese ears. But the smiles this turn of events has brought to the faces in Kasumigaseki may sour in the months ahead, as Japanese officials get to know some of their counterparts on the Bush team. Bush officials have little experience to prepare them for handling any Asian financial crisis many Wall Street analysts fear may be looming.

And the Bushies' affection for Japan is often counterbalanced by an antipathy toward China and a desire for changes within Japan that may quickly strain Tokyo-Washington relations.

Given Bush's inexperience with international issues and lack of familiarity with Asia, his top aides, starting with vice president Cheney and including key Cabinet officials and their top assistants, will have great influence on US policy toward the region. In all fairness, it is too early to judge eventual Bush economic and foreign policy because many of his personnel are not yet in place. But a review of those who have been named and who are expected to get key jobs in the weeks ahead provides some insight into how the Bush administration is likely to deal with Japan, Asia and issues affecting the region.

Of course, it's not who shapes US foreign policy, but what they believe that counts. And there's every indication that the world view of most of the new Bush team was formed during the Cold War. Traditional diplomatic and military concerns will be driving American foreign policy in Asia, not concerns about globalization.

"My concern," said Montana's Senator's Max Baucus, the senior Democrat on the Senate Finance Committee, "is that the new administration will make trade politically subservient to military policy."

Words mask demand

Moreover, what little is known about the Asia policies of Bush intimates suggests that their rhetorical embrace of Japan, especially on security matters, masks very tough, possibly unachievable demands for japanese reforms. And that their economic views are muddled. Traditionally, the American vice-president has had few foreign policy responsibilities, except, in the words of then vice-president Lyndon Johnson, to attend the funerals of Third World dictators.

Bill Clinton's vice president, Al Gore, did assume a special liaison role with Russia. And George Bush's vice president, Dick Cheney, can be expected to play an even greater role in international affairs. Cheney has surrounded himself with more than a dozen foreign policy and military experts. With the shrinking of the staff of the White House National Security Council, Cheney's already considerable experience as a former Defense Secretary will carry even more weight in administration debates. In particular, expect Cheney to tough on China, supported by the views of two aides -- Lewis Libby, Cheney's chief of staff, and C. Dean McGrath Jr, the vice president's deputy chief of staff, both of whom staffed last year's Congressional Cox commission that contended that China should be punished for stealing US nuclear weapons secrets. Cheney has also been stocking the defense department with outspoken allies, many of whom are ardent advocates of US military intervention in trouble spots around the world. Their appointments help Cheney by serving to counterbalance what he perceives to be secretary of state Colin Powell's military pacifism. "His guiding principle is toughness," says an associate of Cheney's. "He's not so much an ideas guy. He just doesn't want to take any crap from adversaries."

White House National Security adviser Condoleeza Rice, President Bush's personal foreign policy aide, is a Russia expert who knows little about Asia. She is a hard liner who believes that trade policy should be the handmaiden of security concerns. She has argued that frequent public criticism of an ally like Japan undermines the chances that Tokyo will respond in a crisis. So she can be expected to be resistant to trade pressure on Japan. Her hiring of Gary Edson, the chief of staff to former US trade representative Carla Hills, to handle international economic issues on the national security council suggests she wants play more of a role in trade matters than any of her predecessors.

Given Rice's lack of Asia experience, the National Security Council's top Asia expert, Torkel Patterson is likely to have greater policy influence than normal for a person in that job. A former Navy captain, he lost his naval career when the ship he was captaining accidentally ran aground. Patterson was the assistant Asia expert on the NSC staff under Bush's father. He knows Japan quite well, he is fluent in Japanese, but really doesn't know China.

Some in Washington's Asian policy community fear he may be in over his head in this new job. The China portfolio on the National Security Council will be handled by Garrett Gong, now with the Center for Strategic and International Studies.

Gong, a Chinese Mormon, is close to business and viewed as "soft" on China by many conservatives.

Secretary of State Colin Powell is no Asia expert, although he did spend time in both South Korea and Vietnam during his military career. He has expressed skepticism about the Clinton administration's engagement efforts with North Korea. And his Powell Doctrine, enunciated during the first Bush Administration, which calls for limited use of US forces around the world and only then where they have a clearly defined mission, overwhelming superiority and an exit strategy, could be severely tested in Asia, where it would seem to rule out the use of GIs in Indonesia, for example.

Inevitable battle

Early on Powell has been surrounding himself with foreign service officers and middle-management types. "He only wants managerial technocrats," says one conservative candidate passed over for a state department job. Such comments foreshadow an inevitable battle between conservative republicans, and their champions in the Bush administration, such as Cheney, Secretary of Defense Rumsfeld and others, and Powell. But Powell is not confining himself to traditional foreign policy issues in his first month in office. In a recent telephone call between Powell and Australian foreign minister Downer, Powell discussed the possibility of a US-Australian free trade agreement, to be discussed further when the Australian prime minister Howard comes to Washington this summer.

Foggy Bottom Asia policy will largely be set by deputy Secretary of State Richard Armitage, one of Powell's closest personal friends and a man with deep experience in Japan, Korea and the rest of Asia. His Armitage Report, published in October, 2000, called for Japan to assume far greater responsibilities for Asian security. He believes that an enhanced US-Japan security relationship would alter the power balance in northeast Asia by increasing US leverage in dealings with China and North Korea. The result would be increased regional stability. Of course, assumption of such an enhanced security role would require changes in the Japanese constitution.

Slow, sensitive moves

Some American observers have expressed concern that Armitage might push Tokyo too far too fast, creating new trans-Pacific tensions contradictory to his stated goal of embracing Japan as America's traditional Asian ally. But those who know Armitage believe he fully appreciates Japan's internal political resistance to a more robust security role in Asia and that he will move slowly and sensitively. Even four years ago, when he chaired a Council on Foreign Relations study group on Japan's security role, Armitage rejected pushing Tokyo to do more than it was capable of doing.

Day-to-day Asian policy will be handled by the new assistant Secretary of State for East Asia, Jim Kelly, a big, bluff Irishman and a former Navy captain, who recently has been running the Honolulu-based Asian arm of the Center for Strategic and International Studies. From his Pentagon days Kelly has very good ties on Capitol Hill because of his reputation as a straight talker who was always prepared with all the answers. He's described as a man with a great Asian rolodex, including strong ties in Japan. And he also has very close professional relations in Taiwan, which could tilt his views on China. His weakness, if any, is that he doesn't know Indonesia, a powder keg issue he will have to deal with early on. Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld was the chairman of a Clinton-appointed independent commission that concluded that China's rapid buildup of naval and missile forces could pose a threat in East Asia. This view has led Bush advisers to cast China as a "strategic competitor" rather than to refer to China as a "strategic partner", the term favored by the Clinton Administration. Bush aides strenuously argue that they do not favor Chinese containment, a series of Asian alliances surrounding China intended to check Beijing's regional influence. But, as one former Clinton Defense Department official quipped: "I tell them they can think containment but that they should talk engagement. But they really want containment." An internal fight over China policy maybe the first bush administration big blowout. Conservatives consider Powell to be too close to foreign service officers who are known for their conciliatory stance toward Beijing. Moreover, they fear he will attempt to blunt their hawkish views toward China. Rumsfeld, by contrast, cautions that china intends to challenge US influence in Asia and accuses those who doubt china's stance of "self-delusion." The battle may be joined early on because the administration must soon decide whether to approve a request from Taiwan for a sizable arms sale package. Other controversies surround Rumsfeld. The Rumsfeld commission also cited North Korea as a rogue nation whose missile program justifies creation of a US national missile defense program. Strong NMD support within the Bush Administration threatens to drive a wedge between Washington and Beijing (because China, not North Korea, is the obvious target of the program), creating possible problems for Tokyo in its relations with China. In addition, the Bush Administration will want Japan to help fund NMD, but is not likely to be willing to share key technologies with Japanese firms.

Back the pentagon

In Rumsfeld's already emerging struggle with Powell and the State Department, bet on the Pentagon. The Pentagon will have a budget next year in excess of US$300 billion. The state department will be lucky if it receives one-tenth that amount. Rumsfeld is also building his own little empire of hard liners. At thinktanks across Washington, conservatives whom Powell has locked out of the state department have been rerouting their resumes across the Potomac. For example, Robert Manning, currently a senior fellow at the council on foreign relations and a hard liner on North Korea policy, is in line to head up the policy planning operation at defense. "Because of the enormous resources at its disposal," explains General William Odom, the former National Security Agency chief and senior fellow at the Hudson Institute, "the Pentagon defines foreign policy in ways no other department, including the State Department, can."

Paul Wolfowitz, Rumsfeld's deputy secretary, is a former US ambassador to Indonesia, who was the undersecretary of Defense for policy during the first Bush administration. Wolfowitz is a defense hawk and one of many in the new Bush team who favors active efforts to overthrow Saddam Hussein. "Paul never met a war he didn't like," said one friend. The prevalence of this hard line on Iraq among the many Bush advisors who seem ashamed of their failure to knock out Saddam Hussein during the Persian Gulf War is technically not an Asian policy issue. But it could have severe repercussions on Japan and the region if such aggression leads to another Middle East war, with a resultant cut in oil supplies and a global recession. On the economic front, the key White House policy maker is Larry Lindsey, a former member of the board of the Federal Reserve. In a speech at the American Enterprise Institute in December of last year, he advocated quiet diplomacy toward Japan on economic matters. "Monetary and fiscal policies are fundamentally a matter of domestic political concern, not for intergovernmental relations," he said. "Japanese fiscal reform can only be done by Japanese politicians accountable to Japanese voters."

Lindsey went on to propose US acceptance of a rise in its already record trade deficit with Japan in return for Tokyo's cutting its sky-high governmental debt. He also implied support for some kind of exchange rate management and implicitly advocated some bilateral effort to open markets between Japan and the US. Lindsey's influence on domestic economic policy is unquestioned. His ability to ultimately shape US foreign economic policy has yet to be tested. Foreign economic policy is now under the control of the National Security Council, evidence that it may be subordinated to foreign policy concerns. It is also unclear what Lindsey's role will be vis-a-vis Paul O'Neill, the Treasury secretary and his Treasury team, none of whom have particular expertise in international financial policy or experience in dealing with financial crises.

O'Neill, while by all accounts an enlightened industrialist, was in Pittsburgh, running Alcoa, during the 1997 Asian economic crisis. He's not part of the small club of people who have lived through financial meltdowns first hand, earning the trust and respect of his counterparts abroad through shared trauma. He can't call up the head of the Bank of Japan and have the frank, personal, shorthand discussion that is often necessary in emergencies. He'll have to build such relationships on the job.

Policy bears watching

And while O'Neill told Congress during his confirmation hearing that he favored a strong dollar, commodity industries tend to favor a weak dollar. This predisposition, combined with the prominence in the Bush Administration of former oil executives Cheney and Commerce Secretary Dan Evans, suggests Bush dollar policy bears watching for signs that Washington's commitment to a strong dollar (and thus a weak yen) may be weakening. O'Neill's lack of understanding of Japan is already raising serious questions in Washington. On Feb. 5, for example, he told the New York Times, that Japan needed greater "price competition", like that which revived the US economy a decade ago. And that he wasn't interested in vague discussions of Japan's myriad regulations, another thinly veiled swipe at the Clinton negotiating history. "If O'Neill really believes what he said," commented one American Japan expert, "then he doesn't understand the first thing about how Japan works".

"The obstacles to price competition in Japan are regulation and ineffective competition policy enforcement," said James Southwick, a former US trade negotiator with Japan. You can't promote price competition in Japan without dealing with government policies."

O'Neill's comments reflected a naive American presumption that if US officials could just sit down with the Japanese and "talk turkey" Japanese officials would see the error of their ways, adopt American practices and their economy would miraculously be on the path to prosperity. He seems blithely unaware that this dialogue has been going on for two decades, that reform in Japan is much more difficult than he thinks and that the political reality in Japan makes the reforms he desires far more complicated than he imagines.

O'Neill's chief deputy will be Kenneth Dam, the deputy secretary of State early in the Reagan Administration, who served on Alcoa's board and who worked with O'Neill as a budget analyst in the Nixon administration. Dam, a lawyer and former IBM executive, has written several books on international trade, but has no experience in the financial sector and no particular expertise on Asia. He will be a strong voice for multilateralism in interagency debates, a possible antidote to the growing enthusiasm within the administration for a Western Hemisphere trade deal.

John Taylor will be the undersecretary of Treasury for international affairs, the chief interlocutor with the deputy minister of Finance in Tokyo.

No treasury veterans

A Stanford University professor and member of the White House Council on Economic Advisers in the first Bush Administration, Taylor's academic work has focused on monetary and fiscal policy and inflation. He has no financial market experience. The absence of a Wall Street veteran in any prominent decision-making role at the Treasury Department is troubling. "We're in an era where financial market experience is a surrogate for understanding change." argued Jeffrey Garten, dean of the Yale School of Management. Wall Street veterans, who have experienced stock market and exchange rate volatility on a daily basis, are intuitively prepared to deal with the constant state of flux in the world economy. Finally, the Bush transition team's initial effort to boot the US Trade Representative out of the Cabinet reflected a desire to return to the good old days, when trade disputes over flat glass didn't complicate America's security ties with Japan. While USTR ultimately retained its seat at the Cabinet table, the new USTR Robert Zoellick almost didn't get the trade job because his expansive vision for US foreign economic policy clashed with the more traditional foreign policy views of those closer to Bush. Given the power of perception in Washington, even a hint of a lack of Oval office clout may prove debilitating for Zoellick. Moreover, the fact that Commerce Secretary Evans is one of the president's oldest friends and reportedly is covetous of a bigger personal role in trade policy will only compound Zoellick's turf and stature challenges.

Unlike many of his predecessors, Zoellick has wrestled with the complications of US foreign economic policy for years, in senior posts at Treasury and State. He has close personal ties with EU trade minister Pascal Lamy and Japanese officials.

"He has the capacity to articulate a national vision that integrates trade into US geo-political goals and objectives," said Alan Wolff, a former deputy US trade representative. He is on record favoring a US-Japan free trade agreement and can be expected to react favorably to any proposal to study closer bilateral economic ties. With many key jobs still to be filled, it would appear that the Bush Administration will fulfill its campaign promises and shift the focus of US foreign policy away from China and toward Japan and move away from an emphasis on trade problems in the Asia region and spend far more time on security concerns. But it also appears that the new administration has no people with any experience dealing with financial crises, which could pose a problem if there is Asian market turbulence in the months ahead.

More broadly, despite all its rhetoric about improving relations with Japan, the administration, in its first few weeks, appears a bit befuddled on how to proceed, as highlighted by the comments of O'Neill and Lindsey, the internal contradictions of the Armitage report and the infighting between Powell and Cheney/Rumsfeld. "O'Neill has not thought through what this all means, " said a former USTR negotiator, "and so he's raising the same risk of dashed expectations as the Armitage report did on strategic cooperation ... neither of them seem to understand the basic economic and political realities operating in Japan today."

Its ironic that a business-oriented GOP administration in Washington is so dominated by foreign policy experts. And that an administration that campaigned on better understanding Japan is already demonstrating a lack of understanding of what they once called the US's most important Asian relationship.

Bruce Stokes is the senior fellow for Economic Studies at the Council on Foreign Relations in Washington.

In their recent op-ed “Trump Should Rein In Taiwan” in Foreign Policy magazine, Christopher Chivvis and Stephen Wertheim argued that the US should pressure President William Lai (賴清德) to “tone it down” to de-escalate tensions in the Taiwan Strait — as if Taiwan’s words are more of a threat to peace than Beijing’s actions. It is an old argument dressed up in new concern: that Washington must rein in Taipei to avoid war. However, this narrative gets it backward. Taiwan is not the problem; China is. Calls for a so-called “grand bargain” with Beijing — where the US pressures Taiwan into concessions

The term “assassin’s mace” originates from Chinese folklore, describing a concealed weapon used by a weaker hero to defeat a stronger adversary with an unexpected strike. In more general military parlance, the concept refers to an asymmetric capability that targets a critical vulnerability of an adversary. China has found its modern equivalent of the assassin’s mace with its high-altitude electromagnetic pulse (HEMP) weapons, which are nuclear warheads detonated at a high altitude, emitting intense electromagnetic radiation capable of disabling and destroying electronics. An assassin’s mace weapon possesses two essential characteristics: strategic surprise and the ability to neutralize a core dependency.

Chinese President and Chinese Communist Party (CCP) Chairman Xi Jinping (習近平) said in a politburo speech late last month that his party must protect the “bottom line” to prevent systemic threats. The tone of his address was grave, revealing deep anxieties about China’s current state of affairs. Essentially, what he worries most about is systemic threats to China’s normal development as a country. The US-China trade war has turned white hot: China’s export orders have plummeted, Chinese firms and enterprises are shutting up shop, and local debt risks are mounting daily, causing China’s economy to flag externally and hemorrhage internally. China’s

During the “426 rally” organized by the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and the Taiwan People’s Party under the slogan “fight green communism, resist dictatorship,” leaders from the two opposition parties framed it as a battle against an allegedly authoritarian administration led by President William Lai (賴清德). While criticism of the government can be a healthy expression of a vibrant, pluralistic society, and protests are quite common in Taiwan, the discourse of the 426 rally nonetheless betrayed troubling signs of collective amnesia. Specifically, the KMT, which imposed 38 years of martial law in Taiwan from 1949 to 1987, has never fully faced its