Careful scrutiny is in order when it comes to examining recent changes in the regulations of China's capital market. As part of ongoing reform of the financial sector, China Securities Regulatory Commission (CSRC) announced that domestic residents with legally-held foreign currencies could open and trade on a stockmarket that was open only to foreign investors.

There has been much excitement about allowing expanded trading on this so-called B-share market. A superficial assessment of this move would suggest that Beijing is liberalizing the financial sector. However, these reforms provide a way to close a gap in its capital controls. With substantial increases in foreign currency savings held by domestic residents, domestic banks have been able to divert these savings overseas for investment. This move is also an admission of the wretched performance of a mutant market created with two heads to serve Beijing's capital control policy. The sad truth is that nothing of substance will change even with full consolidation of China's stockmarkets. In fact, things might become worse, at least for China's beleaguered and badly-served savers. This is because the state-owned banks have squandered much of the hard-earned savings of Chinese depositors by lending to poorly-run state-owned enterprises (SOEs). As it is, somewhere between 25 and 40 percent of those outstanding loans are non-performing.

Given that most of the listed companies are the same SOEs that are delinquent borrowers, this gives them another shot at high jacking China's domestic savings. It is no secret nor should it be a surprise that the central government will benefit mightily since it has majority interests in most of the listed companies.

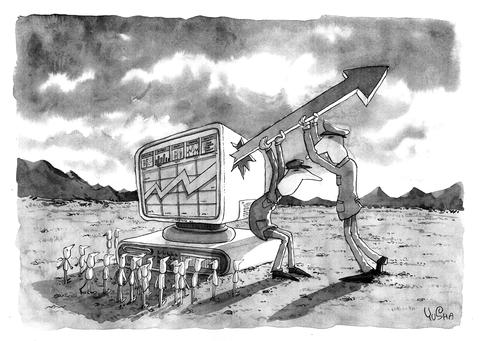

ILLUSTRATION: YU SHA

And these funds at stake are not small potatoes. Foreign currency savings of Chinese residents are estimated to be as much as US$75 billion.

It would be bad enough if investors were simply at risk from the many irregularities in the share markets arising from insider trading and price manipulation schemes. Without transparency and shoddy accounting standards, it almost impossible to track the performance of listed enterprises in a reliable manner. Even so, risks of losses from these illegal acts are probably less than from what amounts to a cynical expropriation by the Chinese government.

If Beijing were acting in the best interests of individual savers, they would be allowed to place their hard-currency holdings anywhere in the world. Or if the funds must be kept captive in the domestic market, the overall economy would be better served if they went into the private sector since sustained growth will require allowing private entrepreneurs greater access to capital.

However, none of these funds will find their way to private enterprises that already have difficulty finding funds from the state-owned banks. Instead of promoting private sector growth, SOEs will be able to use the stock market to continue their inefficient operations. This is especially discouraging since no company has been delisted despite having broken the rules. Although delisting procedures are to be announced soon, the proof will be in the pudding. Under China's securities law and company law, a listed firm can be delisted from the stock market after three consecutive years of losses. Yet the regulations do not specify how soon loss-making firms will be removed under these conditions.

One large retail enterprise, Zhengzhou Baiwen, remains near bankruptcy but has yet to be removed from the stock exchange. And Zhonghao, an enterprise listed on the Shenzhen exchange, has indicated that it has suffered its fourth consecutive year of losses.

At fault in all this is Beijing's gradualist approach to reform that inevitably leads to disappointments, inefficiencies and distortions. Assume that the ultimate goal is for China to have a market economy and think of that result as a means of conveyance that takes the Chinese from the present to the future.

If you begin with one wheel and everyone climbs aboard waiting for the thing to move forward, they will surely declare that reform is getting them nowhere. Adding another wheel and another will not change matters until the whole thing is completed.

Just as an automobile requires 4 wheels plus an engine, transmission and so on, so does a market economy require a whole set of supporting institutional arrangements before it can deliver on its promise. While a market economy requires a capital market and allowing domestic residents to trade on all markets is an improvement, it ain't yet a car and will not be anytime soon.

Inevitable failures in the future should be blamed on how Beijing is approaching reform rather than its goal of a market economy. For example, beginning in 1995, China initiated the "modern enterprise system" with the aim of transforming the SOEs into modern corporations to improve their efficiency. However, separating ownership from management in a corporate structure introduce a principal-agent problem whereby owners must curb managers from looking after their own personal interests.

Although the decentralization of decision-making by managers has gone hand-in-hand with changing incentives for workers whose productivity has increased, SOE performance has shown little improvement. This is because China's SOEs have ineffective internal and external mechanisms for monitoring their behavior.

Systems of corporate governance operate to resolve these principal-agent problems. From a macro standpoint, effective corporate governance structure requires a supporting "institutional infrastructure". This includes a functioning domestic capital market and a banking system that lends on the basis of commercial that operate within an non-arbitrary legal framework. From a micro standpoint, there must be a clear separation of administrative and commercial decisions made within SOEs.

On the one hand, Beijing has been unable to carry out successful oversight over the management of SOEs due to high monitoring costs. These high costs occur due to the lack of an open capital market to assign and assess risks or from problems with information flows. On the other hand, external conditions for good corporate governance structure are lacking.

As long as the SOEs operate without good corporate governance, they will contribute to macroeconomic instability. Subsidies used to keep them open will put pressures on the central government to run budget deficits and cause the public-sector debt to balloon.

Their operations will contribute to price instability. In the past, an insatiable demand for credit contributed to inflation.

Most of the problems with China's economy arise from the contradictions associated with the oxymoronic experiment with "market socialism". Unfortunately, Beijing's attempts at economic reform and modernization will always bump up against a system still weighed down by ideology and distortions from decades of communist central planning.

Christopher Lingle is Global Strategist for eConoLytics.com.

In their recent op-ed “Trump Should Rein In Taiwan” in Foreign Policy magazine, Christopher Chivvis and Stephen Wertheim argued that the US should pressure President William Lai (賴清德) to “tone it down” to de-escalate tensions in the Taiwan Strait — as if Taiwan’s words are more of a threat to peace than Beijing’s actions. It is an old argument dressed up in new concern: that Washington must rein in Taipei to avoid war. However, this narrative gets it backward. Taiwan is not the problem; China is. Calls for a so-called “grand bargain” with Beijing — where the US pressures Taiwan into concessions

The term “assassin’s mace” originates from Chinese folklore, describing a concealed weapon used by a weaker hero to defeat a stronger adversary with an unexpected strike. In more general military parlance, the concept refers to an asymmetric capability that targets a critical vulnerability of an adversary. China has found its modern equivalent of the assassin’s mace with its high-altitude electromagnetic pulse (HEMP) weapons, which are nuclear warheads detonated at a high altitude, emitting intense electromagnetic radiation capable of disabling and destroying electronics. An assassin’s mace weapon possesses two essential characteristics: strategic surprise and the ability to neutralize a core dependency.

Chinese President and Chinese Communist Party (CCP) Chairman Xi Jinping (習近平) said in a politburo speech late last month that his party must protect the “bottom line” to prevent systemic threats. The tone of his address was grave, revealing deep anxieties about China’s current state of affairs. Essentially, what he worries most about is systemic threats to China’s normal development as a country. The US-China trade war has turned white hot: China’s export orders have plummeted, Chinese firms and enterprises are shutting up shop, and local debt risks are mounting daily, causing China’s economy to flag externally and hemorrhage internally. China’s

During the “426 rally” organized by the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and the Taiwan People’s Party under the slogan “fight green communism, resist dictatorship,” leaders from the two opposition parties framed it as a battle against an allegedly authoritarian administration led by President William Lai (賴清德). While criticism of the government can be a healthy expression of a vibrant, pluralistic society, and protests are quite common in Taiwan, the discourse of the 426 rally nonetheless betrayed troubling signs of collective amnesia. Specifically, the KMT, which imposed 38 years of martial law in Taiwan from 1949 to 1987, has never fully faced its