Scott McNealy came to New York last week for a product announcement, not a memorial service.

Yet before the audience of customers, industry analysts and journalists was told of Sun Microsystems' new computers last Tuesday, McNealy -- Sun's chairman and chief executive -- spoke briefly of Philip Rosenzweig. A software senior engineer and manager, Rosenzweig, 47, had worked for Sun for more than a decade. His only mistake, McNealy said, was that "he got on the wrong airplane," American Airlines Flight 11 from Boston on the morning of Sept. 11. As McNealy mentioned Rosenzweig's surviving wife and two children by name, his voice broke and he turned aside and sobbed. "I know thousands of people are lost," he said, "but it's so personal."

PHOTO: NY TIMES

McNealy recovered quickly, and after a moment's silence in honor of Rosenzweig, he returned to computers once more. As Sun's president, Edward J. Zander, who next took the stage, explained, "We need to get back to business."

For Sun and companies across the nation, that promises to be a struggle economically as well as emotionally. In the vast, diverse US$10 trillion economy of the US, there is no such thing as a truly representative company. But Sun, an innovative stalwart of the computer industry, was one of the companies that fueled the technology-led economic boom of the 1990s, and this year Sun has been leading the way again -- downward, as its business eroded abruptly and alarmingly while the economy veered toward recession, even before Sept. 11.

Sun's experience in the last few weeks, and the challenges it is now facing, are shared by much of the Corporate US. The landscape of business has been shaken, as if by an earthquake, though one of uncertain force. Consumer confidence and business investment have fallen sharply, but the outlook depends much on what political and military -- and possibly terrorist -- actions lie ahead. The virtual halt of business activity in the week immediately after the attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon has passed, and companies and workers are indeed getting back to business. Still, it is by no means business as usual.

Hurt -- not devastated

Like many companies, Sun has been hurt by the tragedy, but not devastated. Its New York offices occupied the 25th and 26th floors of the south tower of the World Trade Center, and all of its 346 New York employees got out safely. Sun is also a major supplier of technology to the financial industry, including firms like Lehman Brothers, Merrill Lynch and Citigroup's Salomon Smith Barney, all of whom had offices that were destroyed or damaged.

So Sun's suddenly displaced workers dusted themselves off, then scrambled to get Wall Street up and trading again. At times, the company's sales and technical managers even drove trucks filled with replacement computers to clients trying to relocate and revive their operations. In the immediate aftermath of Sept. 11, the New York product introduction -- eventually held last week at the Hudson Theater in midtown Manhattan -- had been scrapped. Sun had arranged to move the event to San Francisco. But after reflection, and prodded by Zander, a Brooklyn native, the Sun marketing team was persuaded to go to New York after all -- partly by leasing three private jets so that the staff, fearful for its security, would not have to fly on commercial airlines.

Now, as the business climate worsens, Sun's executives must rethink their plans and probably retool the company, yet still try to maintain the loyalty and enthusiasm of the work force. Leadership, more than ever, is a delicate balancing act -- attending to the new worries of traumatized employees but also preparing them for the harsh business realities ahead.

McNealy did both in an afternoon meeting last Tuesday with Sun's work force in New York.

At 46, he is known as a combative, outspoken executive given to glib insults aimed at rivals and their products (he calls Microsoft's Windows a "hairball" of software) and spirited declarations of his libertarian conservative views that extol the virtues of Darwinian capitalism. Friends and colleagues say that to understand McNealy's personality, it helps to note that his preferred recreation is hockey and, they add, to watch the way he plays. He just keeps shooting at the goal, always on the attack. He's tough, relentless and single-minded.

It was a different McNealy, though, who began the employees' gathering by observing that some of them had seen and lived through things that no one should have to experience.

"Don't be hard on yourselves," he told them. "Give yourself time to heal, and understand that some these wounds may never heal."Remember, there are 40,000 people around the company who are dying to help in some way." McNealy continued. "Send an e-mail, reach out for help either professionally or personally. And include Eddie and me," he said, referring to Zander.

McNealy, who in 1982 helped to found Sun, spoke of the company as a "family" in a way that seemed heartfelt. "You're all my heroes," he told them. "I'm so relieved that you're all here and safe."

"This all makes an economic recession not so much to deal with," he said. "It sort of puts everything in perspective, huh?"

Later, McNealy shifted gears, addressing the effect of Sept. 11 on Sun's business. Things were bad before, and they were now certain to become worse.

Sun has weathered downturns in the past without shedding workers. Throughout this year, as one technology company after another announced layoffs and downsizing programs, Sun resisted. It held on to its 43,000 employees worldwide and maintained its research and development spending, the corporate seed corn for the future. Instead, Sun cut down on travel, off-site meetings and eliminated the free bagels and doughnuts. It has pared its real estate expenses. It urged Sun workers to take extra, unpaid vacation.

Previously, Sun executives thought the steep fall in the business had bottomed out. Those hopes have been dashed. "That's one of the reasons I'm so mad about what's happened," McNealy said.

"My last resort is taking people out of their jobs," McNealy he said. "It's not about the stock options anymore. It's about the medical coverage, the dental coverage, the salary, the self-respect and knowing that you're contributing."

After the quarter ends Sept. 30, McNealy, Zander and Sun's other top executives will go over the financial results -- numbers that will certainly make grim reading. The executive team, McNealy explained, will then try to assess the outlook for the next three to six months. And, he said, they will make some "very, very tough calls."

"There is no policy at Sun that says no layoffs," McNealy said. "So go work hard. There are still a few days left in the quarter. Make some sales and ship it."

Yet a flurry of orders in the last few days of the current quarter will not help Sun, or other companies, very much. The day after McNealy spoke, Laura Conigliaro of Goldman, Sachs sharply scaled back her estimates of Sun's financial results for the July-September quarter to levels that "even in my wildest nightmare I never would have imagined" a short time ago.

In the last few months, Conigliaro, a leading computer analyst who has followed Sun for years, had reduced her estimates of the company's sales for the quarter to less than US$3.3 billion from US$3.7 billion. Last Wednesday, she reduced her sales figure to US$2.8 billion, and she now estimates that Sun will lose US$210 million in the quarter. For comparison, Sun reported profits of US$510 million on sales of more than US$5 billion in the same quarter a year ago. On Sept. 28, 2000, Sun's stock closed at US$61.81 a share. On Friday, a year later to the day, it closed at US$8.27.

Layoffs, Conigliaro said, now appear inevitable. She does not expect Sun to return to profitability until the first quarter of next year. Still, she sounds optimistic about Sun's long-term prospects. The company, she noted, supplies the computers and software that help power corporate computer networks and the Internet. Sun has emerged from recessions in the past, typically stronger than ever. Sun, she said, is a sound company, strategically, managerially and technologically. "This is an important company," she said, "and it will come back." In the last few weeks, business all but came to a halt for Sun, as it did for so many companies.

Aggressive selling

Zander is the president, but also one of the company's most effective salesmen. In a sense, Zander and McNealy personify the aggressive sales culture at Sun, while Bill Joy, a founder and the chief scientist, represents the research culture at the company, which has delivered a steady stream of innovations, including Java, the Internet programming language.

Never in his career, the 53-year-old Zander recalled, had he experienced anything quite like the week after Sept. 11. "It was scary," he said. He returned from work one day and told his wife, Mona, "I don't think anybody on the planet is buying a computer." His calendar was totally clean, all executive-level appointments canceled by mutual consent. "It would have been bad taste to knock on doors and ask if they wanted to buy computers," he said.

But since about Sept. 20, Zander began making sales calls again, on the West Coast and in New York. In the first 15 to 30 minutes of each meeting, he said, each side would tell its story, how the business and its people had been affected by Sept. 11. But then, Zander said, the talks turned to how the big retailer, manufacturer, media company or government agency planned to deploy information technology in the future and what role Sun might play.

The days are gone when established companies invested in technology at a furious, if not thoughtless, pace out of fear that some Internet start-up might soon put them out of business. "People thought the Internet was a business, but it's not -- it's a technology," said Zander, whose company benefited enormously from the misconception. These days, the conversations with corporate executives are about how to use computing to streamline supply channels, tighten relationships with customers, cut costs and improve productivity.

In a recession, Zander said, companies will stretch out their spending plans. "But I am encouraged because what I don't hear is companies saying they are going to turn away from information technology and computers as a crucial tool of business," he said.

There will be a few difficult quarters ahead, he said, and perhaps it will be a year before strong growth returns. "But I still think this is a great industry that is going to grow faster than others," Zander said. "Nothing that has happened, not even this disaster, has changed that."

The one place where there was a sudden surge of business after Sept. 11 was on Wall Street. Sun's computers and software animate the stock and bond trading desks of many of the big brokerage houses and investment banks. Sun and its employees played a big role in getting Wall Street up and trading again within days of the attacks, from alternate sites after operations in Lower Manhattan were destroyed.

Merrill Lynch, a big Sun customer, had to have its replacement trading floor in Jersey City ready by Sunday morning, Sept. 16 -- for scheduled testing to ensure that trading on the New York Stock Exchange and NASDAQ could resume the next morning. The Sun account team scrambled to arrange for US$15 million of equipment to be shipped in from around the country. To speed the deliveries from the West Coast, Sun put two drivers in each tractor-trailer, so that they could drive without stopping.

Some 40 desktop computers were pulled out of a Sun sales and engineering office in Burlington, Massachusetts. With drivers in short supply and time running out, two people in the New York office, Leslie Maher, a sales manager, and Michael Yenke, a technical specialist, went to Massachusetts and drove the computer-filled truck to New Jersey themselves. They arrived in Jersey City at 5:30am Saturday.

Another Sun customer, Lehman Brothers, had its offices in the World Trade Center and its data center nearby. Lehman also had to set up a new data center in Jersey City, and Chris Wojie, a Sun manager, led a team of 15 people that, working with a reseller, delivered and installed US$14 million worth of equipment -- more than 130 data-serving computers. At Salomon Smith Barney, a Sun team of 25, led by Irwin Morrisey and Steve Nichols, arranged for more than 100 Sun server computers to be shipped in and installed.

"There were no purchase orders or anything for those shipments," said Raymond Tellalian, a vice president in New York who is in charge of Sun's financial services unit. "Our people just went out and got it done. The billing and the paperwork could wait."

Credo for crisis

In a crisis, the Sun employees were practicing an often-repeated credo at Sun: Better to ask forgiveness than seek denial. Occasionally, McNealy, a Harvard graduate with a Stanford MBA, has denied saying it. Yet anyone who has been at Sun a while regards it as an implicit tenet of its irreverent, entrepreneurial culture -- one nurtured by and reflected in McNealy, who, incidentally, named his son Maverick.

Last Thursday, McNealy ventured to the tip of Manhattan to call on a few customers. Mostly, he heard words of appreciation. "I can't say enough about what your people did," Don Alecci, a managing director of Citigroup's technology group, told him, "when you consider that they narrowly escaped a collapsing building themselves, and then worked around the clock to get our trading operations up and running again."

While walking through the financial district, McNealy offered his thoughts on what lies ahead. "It's going to be tough, personally, for a lot of people," he said. "And we're facing a tough couple of quarters, our company and the economy. But you've got to keep the faith. This economy is going to come back, and so is Sun. And every day that something bad doesn't happen, people are getting back to business -- dealing with life."

FREEDOM OF NAVIGATION: The UK would continue to reinforce ties with Taiwan ‘in a wide range of areas’ as a part of a ‘strong unofficial relationship,’ a paper said The UK plans to conduct more freedom of navigation operations in the Taiwan Strait and the South China Sea, British Secretary of State for Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Affairs David Lammy told the British House of Commons on Tuesday. British Member of Parliament Desmond Swayne said that the Royal Navy’s HMS Spey had passed through the Taiwan Strait “in pursuit of vital international freedom of navigation in the South China Sea.” Swayne asked Lammy whether he agreed that it was “proper and lawful” to do so, and if the UK would continue to carry out similar operations. Lammy replied “yes” to both questions. The

‘OF COURSE A COUNTRY’: The president outlined that Taiwan has all the necessary features of a nation, including citizens, land, government and sovereignty President William Lai (賴清德) discussed the meaning of “nation” during a speech in New Taipei City last night, emphasizing that Taiwan is a country as he condemned China’s misinterpretation of UN Resolution 2758. The speech was the first in a series of 10 that Lai is scheduled to give across Taiwan. It is the responsibility of Taiwanese citizens to stand united to defend their national sovereignty, democracy, liberty, way of life and the future of the next generation, Lai said. This is the most important legacy the people of this era could pass on to future generations, he said. Lai went on to discuss

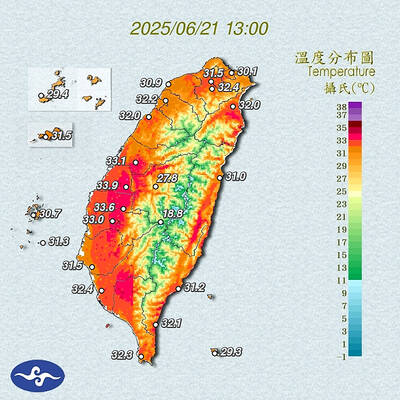

AMENDMENT: Climate change is expected to increase the frequency of high-temperature days, affecting economic productivity and public health, experts said The Central Weather Administration (CWA) is considering amending the Meteorological Act (氣象法) to classify “high temperatures” as “hazardous weather,” providing a legal basis for work or school closures due to extreme heat. CWA Administrator Lu Kuo-chen (呂國臣) yesterday said the agency plans to submit the proposed amendments to the Executive Yuan for review in the fourth quarter this year. The CWA has been monitoring high-temperature trends for an extended period, and the agency contributes scientific data to the recently established High Temperature Response Alliance led by the Ministry of Environment, Lu said. The data include temperature, humidity, radiation intensity and ambient wind,

SECOND SPEECH: All political parties should work together to defend democracy, protect Taiwan and resist the CCP, despite their differences, the president said President William Lai (賴清德) yesterday discussed how pro-Taiwan and pro-Republic of China (ROC) groups can agree to maintain solidarity on the issue of protecting Taiwan and resisting the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). The talk, delivered last night at Taoyuan’s Hakka Youth Association, was the second in a series of 10 that Lai is scheduled to give across Taiwan. Citing Taiwanese democracy pioneer Chiang Wei-shui’s (蔣渭水) slogan that solidarity brings strength, Lai said it was a call for political parties to find consensus amid disagreements on behalf of bettering the nation. All political parties should work together to defend democracy, protect Taiwan and resist