India prohibited wheat exports that the world was counting on to alleviate supply constraints sparked by the war in Ukraine, saying that the nation’s food security is under threat.

Exports would still be allowed to countries that require wheat for food security needs and based on the requests of their governments, the Indian Directorate-General of Foreign Trade said in a notification dated Friday.

All other new shipments would be banned with immediate effect.

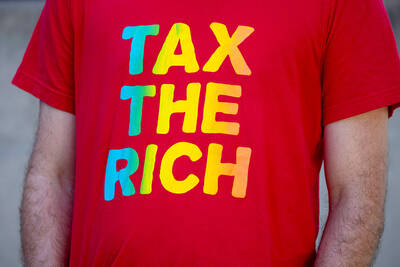

Photo: AP

The decision to halt wheat exports highlights India’s concerns about high inflation, adding to a spate of food protectionism since the war started. Governments around the world are seeking to ensure local food supplies with agriculture prices surging. Indonesia has halted palm oil exports, while Serbia and Kazakhstan imposed quotas on grain shipments.

Curbing exports would be a hit to India’s ambition to cash in on the global wheat rally after the war upended trade flows out of the Black Sea breadbasket region. Importing nations have looked to India for supplies, with top buyer Egypt recently approving the South Asian nation as an origin for wheat imports.

“We now have an environment with another supplier removed from contention in global trade flows,” said Andrew Whitelaw, a grains analyst at Melbourne-based Thomas Elder Markets, adding that he has been skeptical about the high volumes expected from India.

“The world is starting to get very short of wheat,” Whitelaw said.

At present, the US winter wheat is in poor condition, France’s supplies are drying out and Ukraine’s exports are stymied.

Bloomberg News earlier this month reported that a record-shattering heat wave has damaged wheat yields across the South Asian nation, prompting the government to consider export restrictions.

The Indian Ministry of Consumer Affairs, Food and Public Distribution had said it did not see a need to control exports, even as the government cut estimates for India’s wheat production.

Shipments with irrevocable letters of credit that have already been issued will still be allowed, the latest notification said. Traders have contracted to export 4 million tonnes so far in 2022-2023, the food ministry said on May 4.

After Egypt, Turkey has also given approval to import wheat from India, it said.

After the war hampered logistics in the Black Sea region, which accounts for about one-quarter of all wheat trade, India has tried to fill the vacuum. The country targeted to export a record 10 million tonnes in 2022-2023.

However, its domestic challenges have come into sharper focus in the past few weeks. Hundreds of hectares of wheat crops were damaged during India’s hottest March on record, causing yields to potentially slump by as much as 50 percent in some pockets of the country, a Bloomberg survey showed.

That has raised concerns for the domestic market, with millions depending on farming as their main livelihood and food source.

The Indian government said wheat purchases for its food aid program, the world’s largest, would be less than half of last year’s level.

The ban on exports would likely hurt farmers and traders who have stockpiled the grain in anticipation of higher prices.

Controlling wheat exports by India — given uncertainties related to the crop size, the grain procurement program, the war, high fertilizer costs and extreme weather in other growing nations — is a logical move to ensure domestic availability and manage inflation, said Siraj Chaudhry, managing director and chief executive officer of National Commodities Management Services Ltd, a warehousing and trading company.

However, an approach with measures such as a minimum export price and quantitative restrictions would have been better, as a sudden ban throws challenges to trade, affects Indian exporters’ reliability and hits the earning potential of farmers, Chaudhry said.

Vincent Wei led fellow Singaporean farmers around an empty Malaysian plot, laying out plans for a greenhouse and rows of leafy vegetables. What he pitched was not just space for crops, but a lifeline for growers struggling to make ends meet in a city-state with high prices and little vacant land. The future agriculture hub is part of a joint special economic zone launched last year by the two neighbors, expected to cost US$123 million and produce 10,000 tonnes of fresh produce annually. It is attracting Singaporean farmers with promises of cheaper land, labor and energy just over the border.

US actor Matthew McConaughey has filed recordings of his image and voice with US patent authorities to protect them from unauthorized usage by artificial intelligence (AI) platforms, a representative said earlier this week. Several video clips and audio recordings were registered by the commercial arm of the Just Keep Livin’ Foundation, a non-profit created by the Oscar-winning actor and his wife, Camila, according to the US Patent and Trademark Office database. Many artists are increasingly concerned about the uncontrolled use of their image via generative AI since the rollout of ChatGPT and other AI-powered tools. Several US states have adopted

KEEPING UP: The acquisition of a cleanroom in Taiwan would enable Micron to increase production in a market where demand continues to outpace supply, a Micron official said Micron Technology Inc has signed a letter of intent to buy a fabrication site in Taiwan from Powerchip Semiconductor Manufacturing Corp (力積電) for US$1.8 billion to expand its production of memory chips. Micron would take control of the P5 site in Miaoli County’s Tongluo Township (銅鑼) and plans to ramp up DRAM production in phases after the transaction closes in the second quarter, the company said in a statement on Saturday. The acquisition includes an existing 12 inch fab cleanroom of 27,871m2 and would further position Micron to address growing global demand for memory solutions, the company said. Micron expects the transaction to

A proposed billionaires’ tax in California has ignited a political uproar in Silicon Valley, with tech titans threatening to leave the state while California Governor Gavin Newsom of the Democratic Party maneuvers to defeat a levy that he fears would lead to an exodus of wealth. A technology mecca, California has more billionaires than any other US state — a few hundred, by some estimates. About half its personal income tax revenue, a financial backbone in the nearly US$350 billion budget, comes from the top 1 percent of earners. A large healthcare union is attempting to place a proposal before