The phrase is used so often it has become a cliche: “Haiti is the poorest country in the Americas” — but even so, the sentiment fails to capture the stark reality of the Caribbean nation five years after it was leveled by a devastating earthquake.

Haiti’s per capita GDP is the 209th-lowest in the world, behind that of Sierra Leone, North Korea or Bangladesh. The amount of money that Haitians living abroad send home is five times higher than the value that the country’s exports generate.

The 2010 earthquake and ensuing cholera epidemic were only the latest blows to a Caribbean republic that suffered brutal colonialism — France forced its slaves to pay reparations for rising against it — and domestic misrule.

Despite all this, some see potential in the country: Haiti is a low-wage economy lying just south of the huge US market and just north of the emerging economies of Latin America — some have even spoken of its becoming a manufacturing “Taiwan of the Caribbean.”

If that sounds implausible given the state of the country five years after the Jan. 12, 2010, disaster, no one has told Surtab SA, a firm that opened in June 2013 to produce own-brand tablets in Port-au-Prince that run Google Inc’s Android operating system.

The firm boasts that since opening, it has expanded production to 20,000 units last year for the local, Caribbean and African markets, and now provides skilled employment for 60 Haitian workers, despite the stigma of its location.

General manager Diderot Musset said Surtab hopes to triple production this year, but admits that even Haitians are suspicious of the firm’s claims.

“Until they get here and look at the installations, they don’t believe that we are really doing this in Haiti,” he said. “We even had workers who would go home and say that’s what they’re doing, and people not believing them, you know: ‘You’re not making this.’”

“So they had to bring a tablet home and say: ‘Okay, yeah, I made this,’ and still someone would ask: ‘Can you disassemble and reassemble it right now?’” he added.

It is not just a question of perception — Haiti does present severe practical challenges for would-be entrepreneurs, especially in manufacturing:

As a reporter was touring the Surtab plant, with its high-tech “cleanroom” for assembling the wireless devices that give Haitians a cheap means to get online, the power from the nation’s rickety electric grid cut out.

About half of the Haitian government’s income comes from foreign donors of one sort or another and the promised flood of aid in the wake of the 2010 quake never fully materialized or was used up quickly in emergency measures.

However, there has been a recovery — despite an ongoing political crisis — and Haitian President Michel Martelly’s government is bullish about economic opportunity.

The government likes to show off infrastructure projects like the new airport in Cap Haitien it hopes will attract tourists and Haitians proudly show off local products like the Prestige beer flowing from the capital’s rebuilt brewery.

Is this enough of a basis to dream of replacing the worn-out “poorest country” tag with a new “Taiwan of the Caribbean” cliche?

Not so fast. Low-wage manufacturing jobs allow employees to drag some lucky families out of penury, but 80 percent of Haitians live below the poverty line and a modern mixed economy needs a finance and service sector

Robert Maguire, a former US Department of State analyst at the Elliott School of International Affairs, is cautious about the Surtab example.

“I’m not sure that an economy based upon just people sitting in a factory all of the time is a real way to develop a country, absent other elements of the economy,” he said. “It can be a part of the solution, but too often I think it’s seen as the solution.”

Surtab is proud that its performance-based salaries come out at more than one-and-a-half times Haiti’s minimum wage, but its workers grumble that it is not always a steady source of income.

“Compared between when the production line is going and when it’s not, that’s two different things,” Farah Tilus said. “Surtab pays a base salary that’s very low — seriously low — but they offer an opportunity that we can ... make the most of.”

Nevertheless, after all the country has been through, there is a certain pride that comes from seeing each tablet bearing the stamp: “Made in Haiti.”

SEMICONDUCTORS: The German laser and plasma generator company will expand its local services as its specialized offerings support Taiwan’s semiconductor industries Trumpf SE + Co KG, a global leader in supplying laser technology and plasma generators used in chip production, is expanding its investments in Taiwan in an effort to deeply integrate into the global semiconductor supply chain in the pursuit of growth. The company, headquartered in Ditzingen, Germany, has invested significantly in a newly inaugurated regional technical center for plasma generators in Taoyuan, its latest expansion in Taiwan after being engaged in various industries for more than 25 years. The center, the first of its kind Trumpf built outside Germany, aims to serve customers from Taiwan, Japan, Southeast Asia and South Korea,

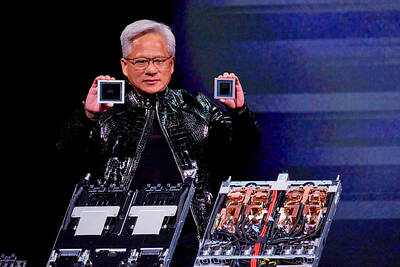

Nvidia Corp chief executive officer Jensen Huang (黃仁勳) on Monday introduced the company’s latest supercomputer platform, featuring six new chips made by Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC, 台積電), saying that it is now “in full production.” “If Vera Rubin is going to be in time for this year, it must be in production by now, and so, today I can tell you that Vera Rubin is in full production,” Huang said during his keynote speech at CES in Las Vegas. The rollout of six concurrent chips for Vera Rubin — the company’s next-generation artificial intelligence (AI) computing platform — marks a strategic

Gasoline and diesel prices at domestic fuel stations are to fall NT$0.2 per liter this week, down for a second consecutive week, CPC Corp, Taiwan (台灣中油) and Formosa Petrochemical Corp (台塑石化) announced yesterday. Effective today, gasoline prices at CPC and Formosa stations are to drop to NT$26.4, NT$27.9 and NT$29.9 per liter for 92, 95 and 98-octane unleaded gasoline respectively, the companies said in separate statements. The price of premium diesel is to fall to NT$24.8 per liter at CPC stations and NT$24.6 at Formosa pumps, they said. The price adjustments came even as international crude oil prices rose last week, as traders

PRECEDENTED TIMES: In news that surely does not shock, AI and tech exports drove a banner for exports last year as Taiwan’s economic growth experienced a flood tide Taiwan’s exports delivered a blockbuster finish to last year with last month’s shipments rising at the second-highest pace on record as demand for artificial intelligence (AI) hardware and advanced computing remained strong, the Ministry of Finance said yesterday. Exports surged 43.4 percent from a year earlier to US$62.48 billion last month, extending growth to 26 consecutive months. Imports climbed 14.9 percent to US$43.04 billion, the second-highest monthly level historically, resulting in a trade surplus of US$19.43 billion — more than double that of the year before. Department of Statistics Director-General Beatrice Tsai (蔡美娜) described the performance as “surprisingly outstanding,” forecasting export growth