In a hot, concrete hut filled with acetylene fumes, an elderly Mongolian miner struggles to contain her excitement as she plucks a sizzling inch-long nugget of gold from a grubby cooling pot and raises it to the light.

Khorloo, 65, and her sons spent the day scrutinizing half a dozen CCTV screens as workers at the Bornuur gold processing plant whittled 1.2 tonnes of ore down to 123g of pure gold that could earn the family as much as US$6,000.

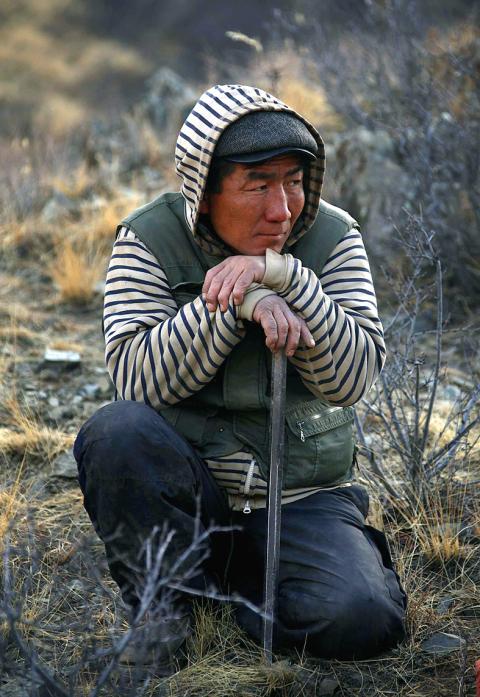

Near the plant, separated from Mongolia’s capital, Ulan Bator, by 100km of rocky pasture and mostly unpaved road, life has remained largely unchanged since Genghis Khan’s “golden horde” rampaged across Asia nine centuries ago.

Photo: Reuters

However, Khorloo is a member of a new horde of at least 60,000 herders, farmers and urban unemployed trying to extract the riches buried in the vast steppe with metal detectors, shovels and home-made smelters.

GREEN PANS

In the past five years, dwindling legal gold supplies and a spike in black market demand from China have made work much more lucrative for Mongolia’s “ninja miners” — so named because of the large green pans carried on their backs that look like turtle shells. For thousands of dirt-poor herders, the soaring prices alone are enough to justify years of harassment, abuse and hard labor.

“It took us a week to dig this out,” Khorloo said, holding the nugget. “But we dug for three years to reach the vein.”

China’s annual gold output reached a record 361 tonnes last year, but demand continues to outstrip supply. While Beijing doesn’t publish full import figures, deliveries from Hong Kong hit 428 tonnes last year, three times more than a year earlier.

Spot international gold prices hit a record high of US$1,920.30 an ounce in September, as investors bought the metal as a safe haven amid uncertainties surrounding the eurozone and its debt. The price has fallen back to about US$1,636, but gold remains at historically high levels after a decade-long rally.

China has certainly driven the gold rush in Mongolia — from the giant $6 billion Oyu Tolgoi copper-gold project currently being developed by Ivanhoe Mines and Rio Tinto to the makeshift holes that honeycomb the hills and valleys of Bornuur.

While the government in Ulan Bator hopes to use growing mineral output to drag its largely pastoral economy into the 21st century, many lawmakers are wary about turning Mongolia into “Minegolia” — a choking, resource-dependent blackspot tearing itself apart to deliver raw materials to China.

However, policies aimed at cutting output to more sustainable levels have played into the hands of the ninjas and a shadowy network of black market traders.

Two decades of ninja activity have already nurtured scores of middlemen linking the underpopulated steppe with the Chinese market. And it hasn’t been difficult to encourage Mongolia’s struggling crop farmers and once-nomadic herders to supply them.

‘CHANGERS’

One English word appears regularly in the ninjas’ Mongolian: The “changers” are a motley group of smugglers who trade black market gold, much of which ends up in China.

“The changers smuggle it to China — the miners do all the work, but those who buy the gold make the money,” said Urantsetseg, one of the many female miners in Zamaar, a gold-producing district south of Ulan Bator.

While all producers are legally obliged to sell their gold to the central bank, the black market is often a better option. Changers can offer prices above the official rate, and they can also avoid the 10 percent tax on sales.

“[Workers] are requested to sell everything to the bank, but they are not really ordered to do so,” said Erdenechimeg Belhkuu, an accountant at Bornuur.

“Some of the supply that goes through our plant is bought officially, but some goes on to the black market, which sometimes just offers higher prices,” the accountant said.

Mongolia’s overall trading volume with China has soared in recent years, primarily in bulk shipments like coal and copper. Mining company officials in Ulan Bator said it was easy — and virtually untraceable — to smuggle a few ounces of gold in one of the thousands of coal trucks heading south.

“For buyers, gold is gold,” said Patience Singo of the Sustainable Artisanal Mining Project run by the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC), which is trying to help the ninjas clean up their production methods and get organized.

Since Mongolia abandoned Soviet-style economic planning in 1990, gold miners large and small have scoured the countryside in search of profit, damaging water supplies with untreated mercury and leaving dunes of toxic tailings in their wake.

ENVIRONMENT

Parliament eventually sought to address Mongolia’s laissez-faire mineral laws, enacting new rules in 2009 that banned mining near rivers and forests and revoking or suspending hundreds of licences. Official gold output fell from a record 21.9 tonnes in 2005 to just more than six tonnes in 2010.

However, the reduction in official supplies has driven up prices, providing incentives for the ninjas to dig away despite growing restrictions on land use. Data is hard to come by, but ninjas continue to supply at least 7 tonnes a year, according to non-governmental organizations.

“The policies have — pardon the pun — driven mining underground,” an executive at a foreign mining firm with interests in Mongolia said.

“You can ban mining and try to protect the environment, but the ninjas don’t listen. I think the only way you can deal with them is by decriminalizing and organizing them, but whether this government is capable of that is another matter,” the executive said.

Mining firms and ninjas forged an uneasy, but often symbiotic relationship. The companies had to defend themselves against raids from ninja crews, sometimes using brute force, but they would also track ninja activity for new discoveries.

Ninjas for their part would gather in their thousands around established mining sites like Zaamar, home at its peak to more than 40 large-scale mining companies.

“In 2007, about 10,000 ninjas came to Zaamar and their situation was like hell, but the government launched a campaign to chase them back to their own areas. Now we have fewer people, but still they come,” Zaamar Governor Bolormaa Dorj said.

Since the crackdown on large-scale mining, Mongolia’s ninjas are now returning to old and abandoned properties and have even started ransacking tailings dams for gold.

Tsetsgee Munkhbayar, an environmental activist who has fired arrows at Mongolia’s parliamentary buildings and attacked mining concessions in protest at the government’s mining policies, said scores of abandoned mines had allowed the ninjas to thrive.

“The ninjas emerged in empty holes excavated by mining companies that ran away without rehabilitating the land — if we can’t deal with the mining companies, we can’t deal with the ninjas,” he said.

To many, Tatu City on the outskirts of Nairobi looks like a success. The first city entirely built by a private company to be operational in east Africa, with about 25,000 people living and working there, it accounts for about two-thirds of all foreign investment in Kenya. Its low-tax status has attracted more than 100 businesses including Heineken, coffee brand Dormans, and the biggest call-center and cold-chain transport firms in the region. However, to some local politicians, Tatu City has looked more like a target for extortion. A parade of governors have demanded land worth millions of dollars in exchange

Hong Kong authorities ramped up sales of the local dollar as the greenback’s slide threatened the foreign-exchange peg. The Hong Kong Monetary Authority (HKMA) sold a record HK$60.5 billion (US$7.8 billion) of the city’s currency, according to an alert sent on its Bloomberg page yesterday in Asia, after it tested the upper end of its trading band. That added to the HK$56.1 billion of sales versus the greenback since Friday. The rapid intervention signals efforts from the city’s authorities to limit the local currency’s moves within its HK$7.75 to HK$7.85 per US dollar trading band. Heavy sales of the local dollar by

Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co’s (TSMC, 台積電) revenue jumped 48 percent last month, underscoring how electronics firms scrambled to acquire essential components before global tariffs took effect. The main chipmaker for Apple Inc and Nvidia Corp reported monthly sales of NT$349.6 billion (US$11.6 billion). That compares with the average analysts’ estimate for a 38 percent rise in second-quarter revenue. US President Donald Trump’s trade war is prompting economists to retool GDP forecasts worldwide, casting doubt over the outlook for everything from iPhone demand to computing and datacenter construction. However, TSMC — a barometer for global tech spending given its central role in the

An Indonesian animated movie is smashing regional box office records and could be set for wider success as it prepares to open beyond the Southeast Asian archipelago’s silver screens. Jumbo — a film based on the adventures of main character, Don, a large orphaned Indonesian boy facing bullying at school — last month became the highest-grossing Southeast Asian animated film, raking in more than US$8 million. Released at the end of March to coincide with the Eid holidays after the Islamic fasting month of Ramadan, the movie has hit 8 million ticket sales, the third-highest in Indonesian cinema history, Film