At his debut appearance before the National Press Club on Friday, Harvey Pitt proudly rattled off an impressive list of accomplishments in his first year as chairman of the US' Securities and Exchange Com-mission, from the record number of cases and temporary restraining orders to his increased efforts to throw unfit officers and directors out of corporate boardrooms.

But what he did not say -- instead it was something he mused to a friend about earlier this year after the collapse of Enron -- may be more revealing about the problems Pitt inherited at the SEC. Over breakfast, he expressed relief to his friend that the commission's failure to examine Enron's financial statements in the last few years was a blessing in disguise. His true nightmare, he said, would have been if the agency had actually reviewed the disclosures and never found anything wrong.

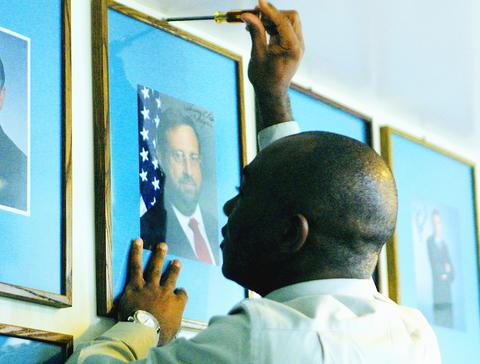

PHOTO: NY TIMES

Once the star in the constellation of regulatory agencies, the SEC over the last decade has lost some of its luster. Although both Republican and Democratic chairmen forged a laudable series of policy initiatives on behalf of investors, the agency's vital infrastructure has been sorely neglected, starved by politicians of adequate money and manpower. That hobbled its ability to keep up with the markets at the worst possible moment -- just as ordinary Americans plowed huge amounts of their savings into the markets.

"There's a corny old saying that you should be fixing the roof when the sun is shining," said Mary Schapiro, president of the National Association of Securities Dealers Regulatory Policy and Oversight Division, and a former commissioner of the SEC and chairwoman of the Commodity Futures Trading Commission. "There simply were not sufficient resources to make that happen."

Low morale, high turnover, meager resources and relatively weak pay hit the agency hard. Reviews like those of Enron's filings were far less frequent. Investigators said the computer system, which was supposed to make it easier for investors, was virtually unusable by officials to perform even the most basic kinds of examinations.

A huge backlog grew of proposed rules for the exchange and other self-regulatory organizations. Significant delays also occurred with greater frequency for the advisory opinions and "no action" letters that were vital for companies and their lawyers seeking advice on ways to raise capital.

"The 1990s were very hard on the agency," said David Becker, who recently returned to private practice after serving as general counsel to Pitt and his predecessor, Arthur Levitt. "To some extent, the agency got hollowed out, losing lots of experienced people."

Now Congress, prompted by public outrage over heavy losses in their investment and retirement accounts, is preparing to substantially enlarge the agency's budget for the first time in decades. But it is not known how quickly that money will be able to turn the tide at the tradition-bound agency.

Red flags

While Enron's recent annual reports and other filings contained crucial clues for investigators -- vital passages on self-dealing transactions were indecipherable and should have raised red flags -- officials said the commission staff never looked at them because it had been forced to sharply scale back its reviews. In the 1980s, the agency had reviewed all of a single company's major filings once every three years. But by last year, the proliferation of filings during the roaring 1990s, combined with the lack of resources, cut that back to once every seven years.

The number of corporate filings received by the agency increased 59 percent, from 61,925 in 1991 to 98,745 in 2000, according to a recent study by the General Accounting Office, an investigative arm of Congress. Over the same period, the staff of lawyers and accountants who review such filings grew by 29 percent, from 125 to 161. By 2000, a paltry 8 percent of overall filings were being reviewed.

An increasing number of regulations adopted in the name of helping investors had hardly helped. An otherwise unassailable and badly needed initiative by Levitt to require reports to be written in "plain English" had made it more difficult and tedious for the reviewers, had provoked even greater wrangling with companies, and had delayed reviews even further.

Moreover, the level of experience of the typical reviewer was in deep decline. The boom market and dreadful work conditions at the agency lured many of the most valuable staff officials elsewhere, creating significantly higher turnover than at any of the other major financial regulatory agencies and leaving the reviewing staff largely in the hands of younger and less experienced lawyers and accountants. Between 1998 and 2000, turnover in some divisions was as high as a third each year, and the average pay was less than half of what was being offered for comparable jobs in the private sector.

Still, the agency reviews are important for assisting enforcement officials looking for cases of wrongdoing and deception, and they are supposed to be a central feature in the multifaceted approach toward policing the markets. But since examiners had basically been given a quota to turn out reviews to satisfy Washington's number crunchers, no one looked at the quality of the reviews. Examiners say they were discouraged from taking on particularly complex filings because they take more time.

Blame game

Like so many other failures of Washington, blame for the rot of the agency's infrastructure is widespread. Some Republicans in Congress, repeatedly dubious of doing anything that would make government bigger, blocked efforts to increase staff salary levels. When he served as chairman of the Energy and Commerce Committee in the late 1990s, Representative Thomas Bliley, was a bitter enemy of Levitt's, and he single-handedly bottled up urgent pleas for more money.

Levitt said on Friday that, while he was proud of his many accomplishments on behalf of investors during his tenure as the longest serving chairman in the agency's history, he deeply regretted not paying more attention to the conditions of the workplace. He also regretted his political failure, despite repeated efforts, to get more money for salaries.

Yet for the first 18 months of his administration, President Bush continued the policy of neglect. He has been slow to name commissioners; agency historians say that the commission has never gone for such a long period of time with only one official, Pitt, confirmed in office.

The failure to install commissioners has already begun to hurt the agency's enforcement program. Earlier this month, an administrative law judge threw out the government's audit-independence case against Ernst & Young because only one commissioner was able to vote on it. A second major case, involving fraud accusations against top executives of Waste Management, faces similar problems.

Still, until just last week, when the White House proposed to add US$100 million to the SEC's budget, Bush's budget staff had fiercely resisted efforts to significantly enlarge its "zero growth" spending blueprint for the agency beyond its current level of US$467 million, fund pay increases ordered by Congress, or even provide most of the relatively modest increases sought by Pitt.

In recent years, the agency has itself become a cash cow, taking in revenues of more than US$2 billion annually. A steady stream of Republican and Democratic leaders of the agency, including Levitt and Pitt, have proposed that Congress permit it to finance itself like the Federal Reserve. But Congress, which is able to maintain some control over the independent and executive branch agencies through the power of the purse, has never taken that view seriously.

House and Senate Democrats have proposed increasing the budget to at least US$750 million, and because of the current furor, officials expect that the White House may have no choice but to support the higher spending.

The US dollar was trading at NT$29.7 at 10am today on the Taipei Foreign Exchange, as the New Taiwan dollar gained NT$1.364 from the previous close last week. The NT dollar continued to rise today, after surging 3.07 percent on Friday. After opening at NT$30.91, the NT dollar gained more than NT$1 in just 15 minutes, briefly passing the NT$30 mark. Before the US Department of the Treasury's semi-annual currency report came out, expectations that the NT dollar would keep rising were already building. The NT dollar on Friday closed at NT$31.064, up by NT$0.953 — a 3.07 percent single-day gain. Today,

‘SHORT TERM’: The local currency would likely remain strong in the near term, driven by anticipated US trade pressure, capital inflows and expectations of a US Fed rate cut The US dollar is expected to fall below NT$30 in the near term, as traders anticipate increased pressure from Washington for Taiwan to allow the New Taiwan dollar to appreciate, Cathay United Bank (國泰世華銀行) chief economist Lin Chi-chao (林啟超) said. Following a sharp drop in the greenback against the NT dollar on Friday, Lin told the Central News Agency that the local currency is likely to remain strong in the short term, driven in part by market psychology surrounding anticipated US policy pressure. On Friday, the US dollar fell NT$0.953, or 3.07 percent, closing at NT$31.064 — its lowest level since Jan.

The New Taiwan dollar and Taiwanese stocks surged on signs that trade tensions between the world’s top two economies might start easing and as US tech earnings boosted the outlook of the nation’s semiconductor exports. The NT dollar strengthened as much as 3.8 percent versus the US dollar to 30.815, the biggest intraday gain since January 2011, closing at NT$31.064. The benchmark TAIEX jumped 2.73 percent to outperform the region’s equity gauges. Outlook for global trade improved after China said it is assessing possible trade talks with the US, providing a boost for the nation’s currency and shares. As the NT dollar

The Financial Supervisory Commission (FSC) yesterday met with some of the nation’s largest insurance companies as a skyrocketing New Taiwan dollar piles pressure on their hundreds of billions of dollars in US bond investments. The commission has asked some life insurance firms, among the biggest Asian holders of US debt, to discuss how the rapidly strengthening NT dollar has impacted their operations, people familiar with the matter said. The meeting took place as the NT dollar jumped as much as 5 percent yesterday, its biggest intraday gain in more than three decades. The local currency surged as exporters rushed to