Far above Sweden’s Arctic Circle, two dozen refugees stepped off a night train onto a desolate, snow-covered platform, their Middle Eastern odyssey abruptly ending at a hotel touted as the world’s most northerly ski resort.

It was Sweden’s latest attempt to house a record influx of asylum seekers.

No one was there to greet them. Only a few, swaying lights flickered on the otherwise empty platform as women fruitlessly wrapped hijabs around their faces to protect themselves from the mountain blizzard.

Photo: Reuters

“Where are we? Is this the final destination?” said Alakozai Naimatullah, an Afghan who worked as a US military translator. He wore tennis shoes, buried in the snow.

His words went unanswered in the disorder of arrival. Their bare hands frozen, husbands, wives and children bent over to drag plastic bags filled with worldly possessions over a steep, snowy path to hotel lights 100m below.

They joined around 600 refugees, mainly from Syria and Afghanistan, holed up for two months in Riksgransen. It is about 200km north of the Arctic Circle and a two-hour bus ride to the nearest town — if the road is not closed by snow.

It is an example of the extremes Sweden is going to in order to house about 160,000 refugees this year in a country of 10 million people. Shelters range from heated tents to adventure theme parks, straining resources.

The sun never rises in Riksgransen at this time of year and temperatures can plummet to minus-30oCelsius. However, the hotel offers food, shelter and security after a dangerous month-long trip from the Middle East by boat, train and bus.

The jovial hotel manager, Sven Kuldkepp, has helped arrange temporary classes and free sledges for children. There is a gym and boxing classes for adults. A room once used for meditation has been turned into a mosque. Yoga mats now face Mecca.

However, the hotel mostly has the feel of an airport lounge with a delayed flight — with a two-month wait. Riksgransen will be home until the ski season starts in February, but many face more than a year’s wait until they get news of asylum requests.

SMARTPHONES

Some refugees, only 100m from ski slopes, still dream of Syrian beaches.

Wael al-Shater was a chef at a 60-table restaurant called Sky View in Homs, specializing in chicken. He had aspirations and applied to study as a chef in Cyprus, but never got a visa. He had friends in Dubai, but did not want to live outside Syria.

“Life was so easy. I made US$1,200 a month,” al-Shater said. “It was so safe that my friends and I used to drive 60km to the beach just to have a coffee late at night at two in the morning and return home.”

Then the war came. His work day was cut in half as fighting erupted in the streets, and his father died of a suspected heart attack during fighting in Homs.

“I could not take him to hospital. He died on the street,” al-Shater said. He paid US$1,200 to be smuggled by boat to Greece 25 days ago and ended up in Riksgransen with his wife, an English teacher.

“In the end I had no option, but to leave or join the killing. Or become a protester and get killed. I had to leave,” he said.

Sitting along dark corridors, refugees’ faces are illuminated by flickering smartphone screens. Some play video games, others Skype friends. Most, like al-Shater, are eager to share memories, using their phones to swipe through photos.

One elderly man showed pictures of his wife and daughter at the beach in the Syrian town of Latakia, a seaside resort and near a Russian military airbase.

Smoking outside in the freezing dark, he raised his face to the sky, as if bathing in Latakia’s imaginary sun.

“Please turn on the sun again,” the elderly man said jokingly.

Another pale, old man had charmed hotel staff with tales of his perfume shop in Syria before he was moved to a Swedish hospital due to a heart ailment.

MEMORIES

Trauma and illness abound. Flu and chicken pox already spread through the hotel. But the most common ailment is insomnia, a sure sign, say nurses, of war trauma.

To make matters worse, few refugees venture outside, spending days in rooms. Many fear taking children out in such freezing temperatures, despite tourists spending thousands of dollars to visit a place famed for views of the northern lights.

“This place is like a desert island,” said nurse Asa Henriksson in a makeshift clinic by the spa’s swimming pool. “It is surrounded by a wall of mountains.”

“When the aurora comes, we tell people to go outside, lay down in the snow, and look up,” she said. “The refugees don’t. Many people here think their children could die in this cold.”

There have been cases of busloads of refugees arriving in the north overnight, having a glance at the surroundings and refusing to get off, insisting on returning to warmer regions.

Some return to southern Sweden while others, like most in Riksgransen, accept their lot. In Riksgransen, many still want to visit the nearest town of Kiruna. They receive around 2 euros a day, some saving for days to buy small toys for children.

Al-Shater still yearns for his homeland.

“There is no human being who does not dream about returning to his country,” he said. “But when it comes to Syria, this is simply impossible. We are planning our future in Sweden.”

A new online voting system aimed at boosting turnout among the Philippines’ millions of overseas workers ahead of Monday’s mid-term elections has been marked by confusion and fears of disenfranchisement. Thousands of overseas Filipino workers have already cast their ballots in the race dominated by a bitter feud between President Ferdinand Marcos Jr and his impeached vice president, Sara Duterte. While official turnout figures are not yet publicly available, data from the Philippine Commission on Elections (COMELEC) showed that at least 134,000 of the 1.22 million registered overseas voters have signed up for the new online system, which opened on April 13. However,

EUROPEAN FUTURE? Albanian Prime Minister Edi Rama says only he could secure EU membership, but challenges remain in dealing with corruption and a brain drain Albanian Prime Minister Edi Rama seeks to win an unprecedented fourth term, pledging to finally take the country into the EU and turn it into a hot tourist destination with some help from the Trump family. The artist-turned-politician has been pitching Albania as a trendy coastal destination, which has helped to drive up tourism arrivals to a record 11 million last year. US President Donald Trump’s son-in-law, Jared Kushner, also joined in the rush, pledging to invest US$1.4 billion to turn a largely deserted island into a luxurious getaway. Rama is expected to win another term after yesterday’s vote. The vote would

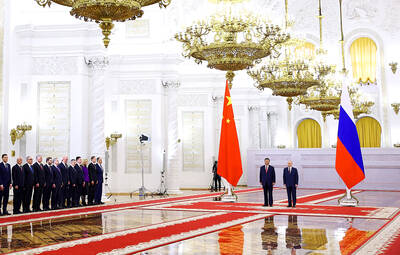

ALLIES: Calling Putin his ‘old friend,’ Xi said Beijing stood alongside Russia ‘in the face of the international counter-current of unilateralism and hegemonic bullying’ Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平) yesterday was in Moscow for a state visit ahead of the Kremlin’s grand Victory Day celebrations, as Ukraine accused Russia’s army of launching air strikes just hours into a supposed truce. More than 20 foreign leaders were in Russia to attend a vast military parade today marking 80 years since the defeat of Nazi Germany in World War II, taking place three years into Russia’s offensive in Ukraine. Putin ordered troops into Ukraine in February 2022 and has marshaled the memory of Soviet victory against Nazi Germany to justify his campaign and rally society behind the offensive,

Myanmar’s junta chief met Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平) for the first time since seizing power, state media reported yesterday, the highest-level meeting with a key ally for the internationally sanctioned military leader. Senior General Min Aung Hlaing led a military coup in 2021, overthrowing Myanmar’s brief experiment with democracy and plunging the nation into civil war. In the four years since, his armed forces have battled dozens of ethnic armed groups and rebel militias — some with close links to China — opposed to its rule. The conflict has seen Min Aung Hlaing draw condemnation from rights groups and pursued by the