Mediterranean-inspired, pastel-colored houses dot the coast and hills of this rural town in the Philippines, dwarfing their traditional counterparts made of unpainted concrete blocks under roofs of corrugated zinc. The larger houses, barely inhabited, many of them empty, belong to overseas workers who plan to return here one day.

Despite their absence, the workers have contributed money to help build roads, schools, water grids and other infrastructure usually handled by local governments. They pay for annual fiestas that were traditionally financed by municipalities, churches and local businesses. Thanks to their help, Mabini became a “first class” municipality last year in a government ranking of towns nationwide, leaping from “third class.”

In one village nicknamed Little Italy, where a quarter of the 1,200 residents are working in Italy, the overseas workers paid 20 percent of the cost to construct a public hall.

PHOTO: AFP

“We couldn’t have finished it without the OFWs,” the village head, Raymundo Magsino, 64, said in an interview inside the building, referring to “overseas Filipino workers.”

Remittances, which the government says have been rising sharply — from US$7.6 billion in 2003 to US$17.3 billion last year — now account for more than 10 percent of the Philippines’ GDP. The payments are also the main factor driving the country’s recent economic growth, which would have otherwise remained stagnant.

Filipinos, who typically work as maids, nurses or service workers abroad, began going overseas in large numbers in the 1980s.

However, critics, including many overseas workers, say the government has developed an unhealthy dependence on the remittances, turning a blind eye to their social costs, especially divided families and the reliance on them to pay for services while failing to build a sound economy that produces good jobs at home.

About 15 percent of the 42,000 residents of Mabini, about 129km south of Manila, live overseas, compared with an estimated national average of 10 percent.

One recent morning, Jocelyn Santia, 40, was packing her bags after two months of vacation here to return to her job as a housekeeper in Milan. She and her husband, who died six years ago, began working in Italy 20 years ago after being recruited by an employment agency.

Her grandparents and a brother raised her four children here, though the two eldest now attend college in Italy. Her sacrifice, she hoped, would yield good, white-collar jobs for her children. However, with her departure — and yet another separation from her two younger children — looming before her, she expressed bitterness about having to leave her family.

“The economy is bad here, salaries are low,” she said. “It’s the fault of the government that so many Filipinos have to go abroad. If there were good jobs here, why would we ever think of going abroad?”

Mabini Mayer Nilo Villanueva said he had often heard this criticism from overseas workers. Villanueva was elected in 2007 by campaigning in Italy and championing the interests of overseas workers. The mayor connected Little Italy to the water grid last year.

Yet, even as Villanueva has sought overseas workers’ investments, he said he worried about the country’s reliance on remittances.

“Many people have become lazy now because they are overdependent on remittances,” he said.

He said the municipality not only counted on investment from its overseas workers, but also had become dependent on their earnings in less direct ways. Most overseas workers here, for example, send their children to private elementary schools, which have smaller class sizes and offer richer educational and extracurricular programs.

“They are helping the municipal government because we are spending less on public schools,” Villanueva said.

At the private Santa Fe Integrated School, which charges an annual tuition of US$370, 80 percent of the 250 students are children of overseas workers. About half have both parents overseas and are being raised by relatives or housekeepers, principal Louella de Leon said.

De Leon said that while the children of overseas workers were better off financially, they lacked discipline and scored poorer grades than the children whose parents were present.

“The kids of OFWs have everything in terms of gadgets — the latest cellphones that you can’t even find in Manila — and they have bigger allowances than even the teachers,” de Leon said. “But they have an attitude. They are arrogant.”

“I don’t understand their parents,” she added. “They are working as maids in Italy and they hire maids here to take care of their own children. They value their money more than their families.”

The national government has highlighted the positive effects of the OFW economy, calling the workers “heroes” and presenting awards for the model OFW family of the year.

In an interview in Manila, Vivian F. Tornea, a director at the Department of Labor’s Overseas Workers Welfare Administration, said the benefits of the remittance economy far outweighed the costs. Tornea denied that the national and local governments had become dependent on remittances, saying that overseas workers’ contributions to building public infrastructure were simply “payback” because they did not pay income taxes.

While the government has welcomed the overseas workers’ remittances, it has done too little to ensure their long-term financial health, critics say. Ella Cristina Gloriane, a personal finance adviser at financial literacy program Atikha, said overseas workers often incurred debts overseas to build their dream houses here.

“That’s one reason why many of them can’t come home,” she said. “They have to keep working to repay their debts.”

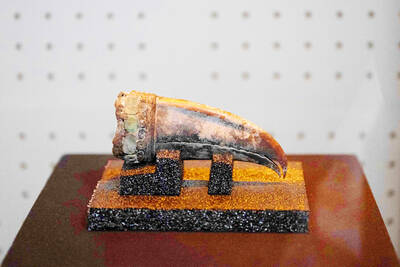

Archeologists in Peru on Thursday said they found the 5,000-year-old remains of a noblewoman at the sacred city of Caral, revealing the important role played by women in the oldest center of civilization in the Americas. “What has been discovered corresponds to a woman who apparently had elevated status, an elite woman,” archeologist David Palomino said. The mummy was found in Aspero, a sacred site within the city of Caral that was a garbage dump for more than 30 years until becoming an archeological site in the 1990s. Palomino said the carefully preserved remains, dating to 3,000BC, contained skin, part of the

‘WATER WARFARE’: A Pakistani official called India’s suspension of a 65-year-old treaty on the sharing of waters from the Indus River ‘a cowardly, illegal move’ Pakistan yesterday canceled visas for Indian nationals, closed its airspace for all Indian-owned or operated airlines, and suspended all trade with India, including to and from any third country. The retaliatory measures follow India’s decision to suspend visas for Pakistani nationals in the aftermath of a deadly attack by shooters in Kashmir that killed 26 people, mostly tourists. The rare attack on civilians shocked and outraged India and prompted calls for action against their country’s archenemy, Pakistan. New Delhi did not publicly produce evidence connecting the attack to its neighbor, but said it had “cross-border” links to Pakistan. Pakistan denied any connection to

TRUMP EFFECT: The win capped one of the most dramatic turnarounds in Canadian political history after the Conservatives had led the Liberals by more than 20 points Canadian Prime Minister Mark Carney yesterday pledged to win US President Donald Trump’s trade war after winning Canada’s election and leading his Liberal Party to another term in power. Following a campaign dominated by Trump’s tariffs and annexation threats, Carney promised to chart “a new path forward” in a world “fundamentally changed” by a US that is newly hostile to free trade. “We are over the shock of the American betrayal, but we should never forget the lessons,” said Carney, who led the central banks of Canada and the UK before entering politics earlier this year. “We will win this trade war and

Armed with 4,000 eggs and a truckload of sugar and cream, French pastry chefs on Wednesday completed a 121.8m-long strawberry cake that they have claimed is the world’s longest ever made. Youssef El Gatou brought together 20 chefs to make the 1.2 tonne masterpiece that took a week to complete and was set out on tables in an ice rink in the Paris suburb town of Argenteuil for residents to inspect. The effort overtook a 100.48m-long strawberry cake made in the Italian town of San Mauro Torinese in 2019. El Gatou’s cake also used 350kg of strawberries, 150kg of sugar and 415kg of