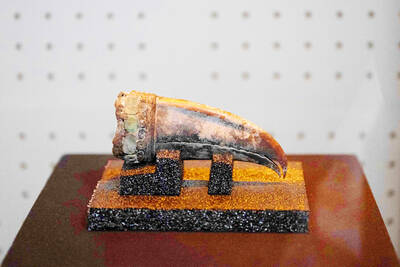

To the usual journalistic armory (famously, ratlike cunning, a plausible manner and a little literary ability), Wang Keqin (王克勤) has added an extra element: The small, red-smudged, battered metal tin that he carries to each interview.

Inside is a sponge soaked in scarlet ink. Like a detective, the 45-year-old reporter compiles witness statements. Then he secures fingerprints at the bottom to confirm agreement.

It is a mark of the thoroughness that has made him China’s best-known investigative journalist, breaking a string of stories that have earned him renown, but also death threats from criminals and wrath from officials.

“The other side is usually much stronger. You have to make the evidence iron-cast,” he said, tapping the tin.

That is not always enough. Last week his boss was removed as the editor of China Economic Times following Wang’s report linking mishandled vaccines to the deaths and serious illnesses of children in Shaanxi Province. Bao Yueyang (包月陽) has been shunted to a minor sister company. Shaanxi officials have claimed the report was wrong; Wang has reportedly said they did not investigate properly, although he declined to comment.

It is the latest case to highlight the zeal of China’s watchdog journalists — and the challenges facing them.

Wang’s CV echoes the development of China’s mainstream media: From life as a propagandist to a role as a watchdog — albeit one on a sturdy chain. He started his career as an official in western Gansu Province in the mid-80s — “a very easy shortcut to wealth and status,” he said, in an interview conducted before the vaccines controversy.

He recalled the propaganda stories he used to churn out and how he cobbled together articles for local media for a bit of extra cash. But as residents sought him out with their problems, he found his conscience stirring.

By 2001 he was “China’s most expensive reporter” — not a reference to his salary, but to the price put on his head for exposing illegal dealings in local financial markets. Soon afterward another report enraged local officials and cost him his job.

“I had problems with black society [gangs], and problems with red society [officials],” Wang said. “I heard there was a special investigation team, [with the target of] sending me to prison.”

Shunned by friends and former colleagues, he was saved by an extraordinary intervention. An internal report on his travails, written by an acquaintance at state news agency Xinhua, reached Zhu Rongji (朱鎔碁), then China’s premier, who stepped in to protect the journalist.

That was in what many Chinese journalists see as a golden age, but in 2004, the authorities responded with tough restrictions on media organizations reporting from areas where they are not based. Though the restrictions are widely ignored, journalists say they have allowed officials to impede investigations and stamp down on the burgeoning of watchdog reporting.

Add Beijing’s drive to promote a “harmonious” image of China and the increasing closeness of economic and political influence, and many are pessimistic.

Some argue that in recent years even state media have offered swifter, fuller coverage of breaking news and touched on more sensitive topics. But to David Bandurski, also of the project, that merely reflects the government’s strategy of actively guiding public thinking.

“Control is moving behind the scenes,” he said. “On the face of it you can do these things, but practically you cannot.”

When the scandal of tainted baby milk broke in 2008, one frustrated editor blogged that his paper had known of the danger but been unable to expose it.

Yet within these constraints, determined journalists fight for — and find — the space to work.

“What decides whether you can do something is not what the law or policy says, but who are you connected to; what someone says at a certain time that gives you cover to go after a certain story,” Bandurski said.

Li Datong (李大同), ousted as editor of Freezing Point magazine in 2006, said the media are able to do more, “not because the government loosened its control, but because the society as a whole is becoming more mature.”

The Internet has also amplified the voice of the mainstream media. Many journalists use personal blogs to publish material censored from their reports.

But journalists know that misjudging the shifting boundaries can damage or end careers, or their publications. And there are new challenges. Zhou Ze (周澤), a journalist-turned-lawyer who is tallying physical attacks and other pressure on the media, said a major concern was officials’ changing tactics to tackle critics.

“In recent years bribery and blackmail accusations have increased,” he said. “When you say it’s defamation, people [ask] what was written in the story and whether it was true. If you say it’s bribery or blackmail, it paints the journalist in a very negative light.”

Readers have good cause for suspicion. Corruption is rife; salaries are low and payment to attend press conferences the norm. Bungs to ensure favorable coverage or bury negative stories are common and have produced “fake journalists,” who threaten to report industrial accidents unless paid off.

Wang fears the bigger problem is “fake news”: propaganda, political or commercial, in the guise of journalism.

In a country where citizens have few ways of holding those with power to account, tough and reliable reporting is all the more essential. Wang has covered topics from land seizures to dangerous mines and the spread of HIV through blood transfusions.

Zhou fears fewer reporters will dare to tackle such issues, and that the public will pay the price. “If reporters’ rights cannot be protected, the rights of ordinary citizens cannot be,” he said.

Archeologists in Peru on Thursday said they found the 5,000-year-old remains of a noblewoman at the sacred city of Caral, revealing the important role played by women in the oldest center of civilization in the Americas. “What has been discovered corresponds to a woman who apparently had elevated status, an elite woman,” archeologist David Palomino said. The mummy was found in Aspero, a sacred site within the city of Caral that was a garbage dump for more than 30 years until becoming an archeological site in the 1990s. Palomino said the carefully preserved remains, dating to 3,000BC, contained skin, part of the

‘WATER WARFARE’: A Pakistani official called India’s suspension of a 65-year-old treaty on the sharing of waters from the Indus River ‘a cowardly, illegal move’ Pakistan yesterday canceled visas for Indian nationals, closed its airspace for all Indian-owned or operated airlines, and suspended all trade with India, including to and from any third country. The retaliatory measures follow India’s decision to suspend visas for Pakistani nationals in the aftermath of a deadly attack by shooters in Kashmir that killed 26 people, mostly tourists. The rare attack on civilians shocked and outraged India and prompted calls for action against their country’s archenemy, Pakistan. New Delhi did not publicly produce evidence connecting the attack to its neighbor, but said it had “cross-border” links to Pakistan. Pakistan denied any connection to

TRUMP EFFECT: The win capped one of the most dramatic turnarounds in Canadian political history after the Conservatives had led the Liberals by more than 20 points Canadian Prime Minister Mark Carney yesterday pledged to win US President Donald Trump’s trade war after winning Canada’s election and leading his Liberal Party to another term in power. Following a campaign dominated by Trump’s tariffs and annexation threats, Carney promised to chart “a new path forward” in a world “fundamentally changed” by a US that is newly hostile to free trade. “We are over the shock of the American betrayal, but we should never forget the lessons,” said Carney, who led the central banks of Canada and the UK before entering politics earlier this year. “We will win this trade war and

Armed with 4,000 eggs and a truckload of sugar and cream, French pastry chefs on Wednesday completed a 121.8m-long strawberry cake that they have claimed is the world’s longest ever made. Youssef El Gatou brought together 20 chefs to make the 1.2 tonne masterpiece that took a week to complete and was set out on tables in an ice rink in the Paris suburb town of Argenteuil for residents to inspect. The effort overtook a 100.48m-long strawberry cake made in the Italian town of San Mauro Torinese in 2019. El Gatou’s cake also used 350kg of strawberries, 150kg of sugar and 415kg of