When Tom Reddoch was growing up in southern Louisiana, on a pencil-thin strip of land flanked on one side by the Mississippi and on the other by a marshy inland waterway, he and his friends used to brag to each other that this was the greatest place on Earth. Children had different expectations back in the 1950s: What they meant was that they would never go hungry.

“The one thing we could be certain of is that we would never starve down here. In those days, this was one great protein factory,” Reddoch says.

Fishing and oyster harvesting was easy, as the nutrient-rich swirl of the freshwater Mississippi and the sea spawned wildlife in endless abundance. But over the course of his lifetime, Reddoch has seen about 70 percent of that extraordinary biodiversity fade away through the combined onslaught of overfishing, the laying of oil pipelines and man-made diversions to the Mississippi.

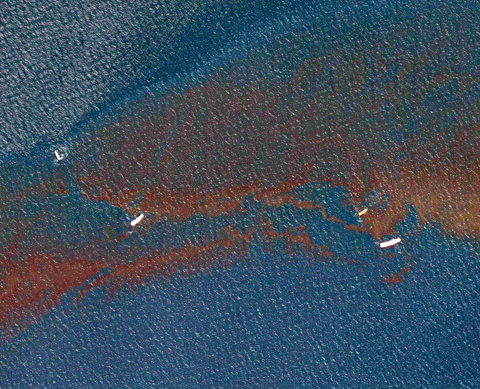

PHOTO: REUTERS

Now the region — which includes nearly half of America’s wetlands — faces its greatest threat of all, one which, Reddoch fears, could kill off what little environmental riches are left.

“This could be the coup de grace. It could be the last blow,” he says.

All along this levee-lined spit of land that stretches from just south of New Orleans down to Venice — a fishing and oil town which, as the name implies, stands on the seafront — people are bracing themselves for the arrival of what could become the worst environmental disaster the US has ever seen. About 80km offshore from Venice is the site of Deepwater Horizon, the oil drilling rig operated by BP that exploded on April 20, leading to the disappearance and presumed death of 11 workers and the spewing of up to 5,000 barrels of oil a day into the sea.

PHOTO: REUTERS

Unless BP succeeds in plugging three leaks some 1,500m undersea, the disaster will within a matter of weeks exceed even the 1989 Exxon Valdez catastrophe off the coast of Alaska.

With the oil being pushed into fragile marshland around Venice by strong winds on Friday morning, Louisiana declared a state of emergency and the Obama administration declared it a spill of “national significance.”

For the residents of Empire, a small fishing town about two-thirds of the way down the spit, this is a spill of personal significance.

“I’ll show you what this means for us,” says Clark Fontaine, the owner of a wooden seafood shack on the side of the main road that has a dilapidated hoarding outside advertising “L VE CRAWF H.”

“Look at these guys!” he says, holding up a handful of plump shrimp, about 10cm in length. The creatures are gray in color, and several have an orange stripe along their backs.

“That’s the eggs they will lay in the marshes that will produce our next crop in August. If we lose these shrimp, then we lose our living for the rest of the year,” Fontaine says.

Mark Franobich has already lost his main income. He works as a diver mechanic in the oilfields in the Gulf of Mexico, and has just been told that all operations have been shut down until further notice in the wake of the Deepwater Horizon explosion. He now relies on selling timber for firewood from his backyard.

“It was just a matter of time before something like this happened. Everyone around here is dependent on fishing: Generations upon generations of them. It’s all they know,” he says.

Nobody knows precisely when the oil slick will strike them hard. Surface deposits have already been spotted being driven into the grassy marshes along the coast, but how quickly it will move up the Mississippi and spread through the inland waterway is unclear. In the docks at Empire a row of oyster boats sit idle, unable to go to sea because of the high winds that are whipping up 2.4m waves, thus hampering the oil clean-up. A Mexican crew is doing odd jobs on board the Lady Marija.

“We don’t know when the oil is going to arrive,” Silvestre Frias says, speaking in Spanish. “What we do know is that when it does, it will shut down everything.”

The Lady Marija brings in about US$10,000 worth of oysters a week, supporting the five crew and the ship’s owner.

“Yes, we’re scared. There will be no work for any of us,” he says.

Reddoch estimates the oil will reach disaster levels as far up the spit as Empire by today at the latest. And that, he says, will have huge consequences for himself and the wider community.

Reddoch’s small business, Down South Services, has two main contracts. The first is to do maintenance work on a nearby fish factory called Menhadden Fisheries, where he employs about 50 workers through the summer.

The factory processes small sardines known locally as Menhadden, which produce some of the highest-grade fish oil in the world. The oil finds its way into Omega-3 vitamin supplements, paint, cosmetics and even lubricant for the space shuttle.

The plant opened its doors just last week for this year’s season, and receives up to eight boats a day, each laden with sardine catches worth up to US$1 million.

“Think about that for a second — when it’s cooking, that’s a lot of business; and all of that will be lost,” Reddoch says.

Down South Services’ other main contract is, fortuitously enough, to provide labor in cases of oil spillages.

He is laying on men to work the booms that are being used to try to prevent the oil coming on land, and once it does his employees will be cleaning up the beaches, marshes and ships.

So what he’s lost with one hand, he’s gained with the other.

“That’s what you call diversification,” he says, adding that it gives him no pleasure to make money out of the final destruction of his childhood paradise.

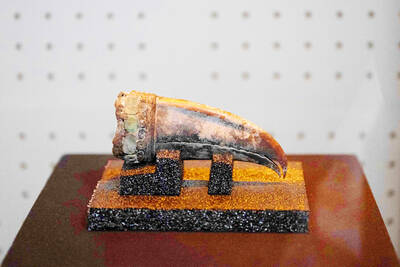

Archeologists in Peru on Thursday said they found the 5,000-year-old remains of a noblewoman at the sacred city of Caral, revealing the important role played by women in the oldest center of civilization in the Americas. “What has been discovered corresponds to a woman who apparently had elevated status, an elite woman,” archeologist David Palomino said. The mummy was found in Aspero, a sacred site within the city of Caral that was a garbage dump for more than 30 years until becoming an archeological site in the 1990s. Palomino said the carefully preserved remains, dating to 3,000BC, contained skin, part of the

‘WATER WARFARE’: A Pakistani official called India’s suspension of a 65-year-old treaty on the sharing of waters from the Indus River ‘a cowardly, illegal move’ Pakistan yesterday canceled visas for Indian nationals, closed its airspace for all Indian-owned or operated airlines, and suspended all trade with India, including to and from any third country. The retaliatory measures follow India’s decision to suspend visas for Pakistani nationals in the aftermath of a deadly attack by shooters in Kashmir that killed 26 people, mostly tourists. The rare attack on civilians shocked and outraged India and prompted calls for action against their country’s archenemy, Pakistan. New Delhi did not publicly produce evidence connecting the attack to its neighbor, but said it had “cross-border” links to Pakistan. Pakistan denied any connection to

TRUMP EFFECT: The win capped one of the most dramatic turnarounds in Canadian political history after the Conservatives had led the Liberals by more than 20 points Canadian Prime Minister Mark Carney yesterday pledged to win US President Donald Trump’s trade war after winning Canada’s election and leading his Liberal Party to another term in power. Following a campaign dominated by Trump’s tariffs and annexation threats, Carney promised to chart “a new path forward” in a world “fundamentally changed” by a US that is newly hostile to free trade. “We are over the shock of the American betrayal, but we should never forget the lessons,” said Carney, who led the central banks of Canada and the UK before entering politics earlier this year. “We will win this trade war and

Armed with 4,000 eggs and a truckload of sugar and cream, French pastry chefs on Wednesday completed a 121.8m-long strawberry cake that they have claimed is the world’s longest ever made. Youssef El Gatou brought together 20 chefs to make the 1.2 tonne masterpiece that took a week to complete and was set out on tables in an ice rink in the Paris suburb town of Argenteuil for residents to inspect. The effort overtook a 100.48m-long strawberry cake made in the Italian town of San Mauro Torinese in 2019. El Gatou’s cake also used 350kg of strawberries, 150kg of sugar and 415kg of