When advocate Govinder Singh rose to make an argument in the Delhi High Court this month, he did what no lawyer had ever done before him and addressed the judge in Hindi.

Singh’s action was generally applauded for striking an overdue blow against a decades-old rule that insists on English — the enduring legacy of British colonial rule — as the working language of the Indian capital’s top judicial bench.

A similar linguistic challenge was thrown down in November last year by Abu Azmi, a newly elected legislator in the Maharashtra state assembly, when he opted to take his oath of office in Hindi, rather than the state language of Marathi.

Azmi’s reward was to be slapped and roughed up on the floor of the assembly by four state ministers of parliament from a right-wing party that campaigns aggressively for the rights of the state’s Marathi-speaking majority.

Language has always been a battleground both within and between nation states, but only in a country as astonishingly diverse as India has it been fought with such frequency and on so many different fronts.

While confrontations in courtrooms or state legislatures grab the media spotlight, smaller skirmishes occur on a daily basis — not least in the homes of the growing number of mixed-language families.

India’s 1961 census recognized 1,652 languages and dialects, while the 2001 version broke it down into a slightly more manageable roster of 29 that are spoken by 1 million or more people, and 122 that have more than 10,000 native speakers.

At the time of independence, the Constitution recognized 14 official languages, but the growth of regional politics soon resulted in a flood of demands for further additions.

Sindhi was added in 1967, three others in 1992 and four more in 2004 to make up the current total of 22, and the Home Ministry is currently considering 38 new requests for inclusion.

The expanding list is something of a nightmare for the central Reserve Bank of India (RBI), which is obliged to see that all official languages are represented on each banknote.

“At the moment we have 17, so yes, it’s true that we are slightly behind,” RBI spokeswoman Alpana Killawala said.

The numbers reflect the importance different communities in India attach to their linguistic and cultural identities and with so many competing for recognition, institutional and personal clashes are inevitable.

Among the booming middle classes, mixed marriages and increased job mobility can leave some couples struggling with a heady linguistic cocktail.

“When we had our son, we made a decision to speak to him in Hindi, which was anyway the common language between my wife and I,” business journalist Jay Shankar said.

Shankar is from the southern state of Kerala and his wife is from the western state of Gujarat. Their mother tongues — Malayalam and Gujarati — are mutually unintelligible and they have always communicated in a mixture of Hindi and English.

When their son was four, they moved to Bangalore, where the dominant language is Kannada, and enrolled their son in an English-speaking kindergarten.

Now 13, he speaks fluent Hindi and English, but neither of his parents’ native tongues.

“For my mother and father this is big, big problem,” Shankar said. “There is a huge communication gap. They can’t relate to what he says at all and they blame me for not speaking Malayalam with him when he was young.”

“It really bothers me that their relationship with their grandson is not what it should be,” he said. “We don’t regret the decisions we made, but it’s been tough.”

Hindi and English are the heavyweights in India’s crowded linguistic arena, and both have been treated with suspicion and even violence since independence in 1947.

According to the 2001 census, about 422 million Indians, or 41 percent of the billion-plus population, speak Hindi, with Bengali a distant second at 8.1 percent.

Anti-Hindi sentiments have a long history and regional language activists opposed to its prevalence exist all over India, especially in southern states like Tamil Nadu, where efforts to impose Hindi triggered bloody riots in the mid-1960s.

“We are against forcing a language on the state,” Tamil Nadu state legislator M.K. Kanimozhi said. “I can’t speak Hindi but I am no less an Indian or patriotic than anybody else.”

Historically, English was the language of domination, status and privilege, but that has changed as India’s middle classes have made the transition from subjects under British colonial rule to citizens negotiating globalization.

“People want to learn English because it means opportunity and access to jobs,” said historian Ramachandra Guha, who advocates compromise in the heated debate over whether local languages are losing out to the demand for English in schools.

“What we as Indians should aim for is not a worship of English or a demonization of English, but an ability to learn it along with other languages. Schools should be bilingual from the beginning,” Guha said.

The number of children enrolled in recognized English-medium schools in India doubled between 2003 and 2008 to more than 15 million, but in a recent ruling the Supreme Court said that the country risked falling behind.

A large English-speaking population has been one of the key factors behind the boom in outsourcing to India, which has seen Western companies set up IT back-up or call centers in cities such as Bangalore and Hyderabad.

“In another 10 years, China will become the world’s largest English-speaking nation,” the two judge bench said. “Today, if you go to China, all little children speak English. In 10 years they will overtake us.”

India’s claim to the title of largest English speaking nation is based on a much quoted survey that found one third of Indians — about 350 million people — could hold a conversation in English, but experts say that proficiency levels vary dramatically.

The Supreme Court warning was echoed by a recent British Council report that highlighted a “huge shortage” of English teachers and quality institutions in India that meant the rate of improvement in English language skills was “too slow.”

“This could threaten India’s English advantage in the global market,” the report said.

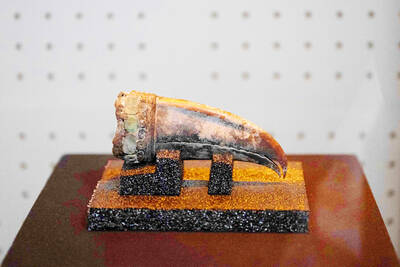

Archeologists in Peru on Thursday said they found the 5,000-year-old remains of a noblewoman at the sacred city of Caral, revealing the important role played by women in the oldest center of civilization in the Americas. “What has been discovered corresponds to a woman who apparently had elevated status, an elite woman,” archeologist David Palomino said. The mummy was found in Aspero, a sacred site within the city of Caral that was a garbage dump for more than 30 years until becoming an archeological site in the 1990s. Palomino said the carefully preserved remains, dating to 3,000BC, contained skin, part of the

‘WATER WARFARE’: A Pakistani official called India’s suspension of a 65-year-old treaty on the sharing of waters from the Indus River ‘a cowardly, illegal move’ Pakistan yesterday canceled visas for Indian nationals, closed its airspace for all Indian-owned or operated airlines, and suspended all trade with India, including to and from any third country. The retaliatory measures follow India’s decision to suspend visas for Pakistani nationals in the aftermath of a deadly attack by shooters in Kashmir that killed 26 people, mostly tourists. The rare attack on civilians shocked and outraged India and prompted calls for action against their country’s archenemy, Pakistan. New Delhi did not publicly produce evidence connecting the attack to its neighbor, but said it had “cross-border” links to Pakistan. Pakistan denied any connection to

TRUMP EFFECT: The win capped one of the most dramatic turnarounds in Canadian political history after the Conservatives had led the Liberals by more than 20 points Canadian Prime Minister Mark Carney yesterday pledged to win US President Donald Trump’s trade war after winning Canada’s election and leading his Liberal Party to another term in power. Following a campaign dominated by Trump’s tariffs and annexation threats, Carney promised to chart “a new path forward” in a world “fundamentally changed” by a US that is newly hostile to free trade. “We are over the shock of the American betrayal, but we should never forget the lessons,” said Carney, who led the central banks of Canada and the UK before entering politics earlier this year. “We will win this trade war and

Armed with 4,000 eggs and a truckload of sugar and cream, French pastry chefs on Wednesday completed a 121.8m-long strawberry cake that they have claimed is the world’s longest ever made. Youssef El Gatou brought together 20 chefs to make the 1.2 tonne masterpiece that took a week to complete and was set out on tables in an ice rink in the Paris suburb town of Argenteuil for residents to inspect. The effort overtook a 100.48m-long strawberry cake made in the Italian town of San Mauro Torinese in 2019. El Gatou’s cake also used 350kg of strawberries, 150kg of sugar and 415kg of