Agricultural scientist Norman Borlaug, the father of the “green revolution” who won the Nobel Peace Prize for his role in combating world hunger and saving hundreds of millions of lives, died on Saturday in Texas, a Texas A&M University spokeswoman said. He was 95.

Borlaug died just before 11pm on Saturday at his home in Dallas from complications of cancer, said school spokeswoman Kathleen Phillips. Phillips said Borlaug’s granddaughter told her about his death. Borlaug was a distinguished professor at the university in College Station, Texas.

The Nobel committee honored Borlaug in 1970 for his contributions to high-yield crop varieties and bringing other agricultural innovations to the developing world. Many experts credit the green revolution with averting global famine during the second half of the 20th century and saving perhaps 1 billion lives.

Thanks to the green revolution, world food production more than doubled between 1960 and 1990. In Pakistan and India, two of the nations that benefited most from the new crop varieties, grain yields more than quadrupled over the period.

“We would like his life to be a model for making a difference in the lives of others and to bring about efforts to end human misery for all mankind,” his children said in a statement. “One of his favorite quotes was, ‘Reach for the stars. Although you will never touch them, if you reach hard enough, you will find that you get a little “star dust” on you in the process.’”

Equal parts scientist and humanitarian, the Iowa-born Borlaug realized improved crop varieties were just part of the answer, and pressed governments for farmer-friendly economic policies and improved infrastructure to make markets accessible. A 2006 book about Borlaug is titled The Man Who Fed the World.

“He has probably done more and is known by fewer people than anybody that has done that much,” said Ed Runge, retired head of Texas A&M University’s Department of Soil and Crop Sciences and a close friend who persuaded Borlaug to teach at the school. “He made the world a better place — a much better place. He had people helping him, but he was the driving force.”

Borlaug began the work that led to his Nobel in Mexico at the end of World War II. There he used innovative breeding techniques to produce disease-resistant varieties of wheat that produced much more grain than traditional strains.

He and others later took those varieties and similarly improved strains of rice and corn to Asia, the Middle East, South America and Africa.

“More than any other single person of his age, he has helped to provide bread for a hungry world,” Nobel Peace Prize committee chairman Aase Lionaes said in presenting the award to Borlaug. “We have made this choice in the hope that providing bread will also give the world peace.”

During the 1950s and 1960s, public health improvements fueled a population boom in underdeveloped nations, leading to concerns that agricultural systems could not keep up with growing food demand.

Borlaug’s work often is credited with expanding agriculture at just the moment such an increase in production was most needed.

“We got this thing going quite rapidly,” Borlaug said in a 2000 interview. “It came as a surprise that something from a Third World country like Mexico could have such an impact.”

His successes in the 1960s came just as books like The Population Bomb were warning readers that mass starvation was inevitable.

“Three or four decades ago, when we were trying to move technology into India, Pakistan and China, they said nothing could be done to save these people, that the population had to die off,” he said in 2004.

Borlaug often said wheat was only a vehicle for his real interest, which was to improve people’s lives.

“We must recognize the fact that adequate food is only the first requisite for life,” he said in his Nobel acceptance speech. “For a decent and humane life we must also provide an opportunity for good education, remunerative employment, comfortable housing, good clothing and effective and compassionate medical care.”

In Mexico, Borlaug was known both for his skill in breeding plants and for his eagerness to labor in the fields himself, rather than to let assistants do all the hard work.

He remained active well into his 90s, campaigning for the use of biotechnology to fight hunger and working on a project to fight poverty and starvation in Africa by teaching new drought-resistant farming methods.

“We still have a large number of miserable, hungry people and this contributes to world instability,” Borlaug said in May 2006 at an Asian Development Bank forum in the Philippines. “Human misery is explosive, and you better not forget that.”

Norman Ernest Borlaug was born March 25, 1914, on a farm near Cresco, Iowa, and was educated through the eighth grade in a one-room schoolhouse.

“I was born out of the soil of Howard County,” he said. “It was that black soil of the Great Depression that led me to a career in agriculture.”

He left home during the Great Depression to study forestry at the University of Minnesota. While there he earned himself a place in the university’s wrestling hall of fame and met his future wife, whom he married in 1937. Margaret Borlaug died in 2007 at the age of 95. They had two children.

After a brief stint with the US Forest Service, Norman Borlaug returned to the University of Minnesota for a doctoral degree in plant pathology. He then worked as a microbiologist for DuPont, but soon left for a job with the Rockefeller Foundation. Between 1944 and 1960, Borlaug dedicated himself to increasing Mexico’s wheat production.

In 1963, Borlaug was named head of the newly formed International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center, where he trained thousands of young scientists.

Borlaug retired as head of the center in 1979 and turned to university teaching, first at Cornell University and then at Texas A&M, which presented him with an honorary doctorate in December 2007.

“You really felt really very privileged to be with him, and it wasn’t that he was so overpowering, but he was always on, intellectually always engaged,” said Ed Price, director of A&M’s Norman Borlaug Institute for International Agriculture. “He was always onto the issues and wanting to engage and wanting your opinions and thoughts.”

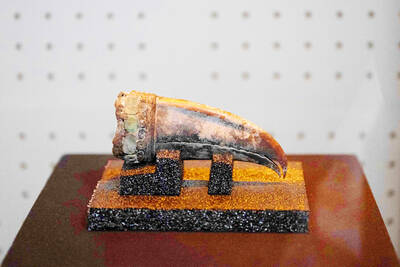

Archeologists in Peru on Thursday said they found the 5,000-year-old remains of a noblewoman at the sacred city of Caral, revealing the important role played by women in the oldest center of civilization in the Americas. “What has been discovered corresponds to a woman who apparently had elevated status, an elite woman,” archeologist David Palomino said. The mummy was found in Aspero, a sacred site within the city of Caral that was a garbage dump for more than 30 years until becoming an archeological site in the 1990s. Palomino said the carefully preserved remains, dating to 3,000BC, contained skin, part of the

‘WATER WARFARE’: A Pakistani official called India’s suspension of a 65-year-old treaty on the sharing of waters from the Indus River ‘a cowardly, illegal move’ Pakistan yesterday canceled visas for Indian nationals, closed its airspace for all Indian-owned or operated airlines, and suspended all trade with India, including to and from any third country. The retaliatory measures follow India’s decision to suspend visas for Pakistani nationals in the aftermath of a deadly attack by shooters in Kashmir that killed 26 people, mostly tourists. The rare attack on civilians shocked and outraged India and prompted calls for action against their country’s archenemy, Pakistan. New Delhi did not publicly produce evidence connecting the attack to its neighbor, but said it had “cross-border” links to Pakistan. Pakistan denied any connection to

TRUMP EFFECT: The win capped one of the most dramatic turnarounds in Canadian political history after the Conservatives had led the Liberals by more than 20 points Canadian Prime Minister Mark Carney yesterday pledged to win US President Donald Trump’s trade war after winning Canada’s election and leading his Liberal Party to another term in power. Following a campaign dominated by Trump’s tariffs and annexation threats, Carney promised to chart “a new path forward” in a world “fundamentally changed” by a US that is newly hostile to free trade. “We are over the shock of the American betrayal, but we should never forget the lessons,” said Carney, who led the central banks of Canada and the UK before entering politics earlier this year. “We will win this trade war and

Armed with 4,000 eggs and a truckload of sugar and cream, French pastry chefs on Wednesday completed a 121.8m-long strawberry cake that they have claimed is the world’s longest ever made. Youssef El Gatou brought together 20 chefs to make the 1.2 tonne masterpiece that took a week to complete and was set out on tables in an ice rink in the Paris suburb town of Argenteuil for residents to inspect. The effort overtook a 100.48m-long strawberry cake made in the Italian town of San Mauro Torinese in 2019. El Gatou’s cake also used 350kg of strawberries, 150kg of sugar and 415kg of