A prison court in military-ruled Myanmar will deliver its verdict in the trial of Aung San Suu Kyi on Friday, a ruling that could see the democracy leader jailed for up to five years, her lawyer said.

Myanmar’s military junta has sparked international outrage for prosecuting the Nobel peace laureate on charges of breaching the rules of her house arrest after an American man swam to her lakeside house in May.

“The verdict will be given this coming Friday,” defense lawyer Nyan Win said after the trial wrapped up with a final reply by Aung San Suu Kyi ‘s legal team.

PHOTO: AFP

Judges Thaung Nyunt and Nyi Nyi Soe indicated to the court at the notorious Insein prison in Yangon that sentencing was expected on the same day.

“If she is released unconditionally she will be home on that day — if not, the sentence will be together with the verdict,” said Nyan Win, who is also the spokesman for her National League for Democracy (NLD).

“We have a good chance according to the law, but we cannot know what the court will decide because this is a political case,” he said.

The court made the announcement yesterday after hearing final comments by lawyers for the 64-year-old Aung San Suu Kyi, her two female aides and US national John Yettaw, in response to closing statements delivered by prosecutors on Monday.

A Myanmar official, speaking on condition of anonymity, said diplomats from Thailand, Japan, Singapore and the US attended yesterday’s hearing.

The verdict is widely expected to be a guilty one given the previous form of the courts, which have handed down heavy sentences to dozens of dissidents over the past year.

But the Aung San Suu Kyi case has been repeatedly delayed amid signs that the regime is trying to seek a way of quelling the storm of international outrage over its treatment of the opposition icon.

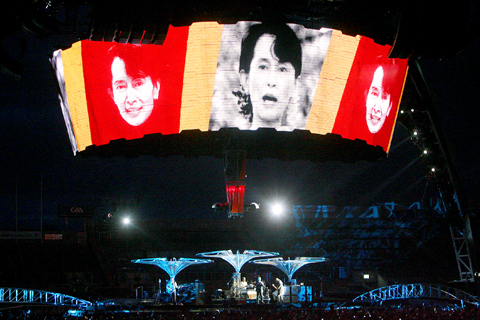

U2 singer Bono announced during a concert in Dublin on Monday that Aung San Suu Kyi had been named Amnesty International’s ambassador of conscience for this year, the rights group’s highest honor.

Critics have accused the junta of trying to keep Aung San Suu Kyi locked up ahead of elections next year.

Aung San Suu Kyi has been in jail or under house arrest for 13 of the last 19 years since the junta refused to recognize the NLD’s landslide victory in the 1990 elections.

Her lawyers say that she was not responsible for the intrusion by Yettaw — who has said that he was inspired by a divine vision that she would be assassinated — and that she was charged under outdated laws.

But Myanmar’s rulers have strongly defended the trial.

State media yesterday made the strongest suggestions yet that Yettaw was an agent of an outside power, possibly the US, and was trying to smuggle Suu Kyi out of detention.

The New Light of Myanmar newspaper said the trial “has not been intentionally created by the government” but was the fault of Yettaw, who “might have been sent to the country by an anonymous country or organization.”

“The aim of his meeting with Daw Suu Kyi has not been known clearly. He even left two chadors [Muslim shawls] and dark sunglasses to her to act herself in disguise. Was it aimed at taking her out of the house?” it said.

The newspaper also pointed out that the route Yettaw used to enter her house was the “ditch beside the US embassy” and said the place he was arrested was 25m from the house of the US charge d’affaires.

“So there are many points to ponder,” the editorial said.

In the sweltering streets of Jakarta, buskers carry towering, hollow puppets and pass around a bucket for donations. Now, they fear becoming outlaws. City authorities said they would crack down on use of the sacred ondel-ondel puppets, which can stand as tall as a truck, and they are drafting legislation to remove what they view as a street nuisance. Performances featuring the puppets — originally used by Jakarta’s Betawi people to ward off evil spirits — would be allowed only at set events. The ban could leave many ondel-ondel buskers in Jakarta jobless. “I am confused and anxious. I fear getting raided or even

POLITICAL PATRIARCHS: Recent clashes between Thailand and Cambodia are driven by an escalating feud between rival political families, analysts say The dispute over Thailand and Cambodia’s contested border, which dates back more than a century to disagreements over colonial-era maps, has broken into conflict before. However, the most recent clashes, which erupted on Thursday, have been fueled by another factor: a bitter feud between two powerful political patriarchs. Cambodian Senate President and former prime minister Hun Sen, 72, and former Thai prime minister Thaksin Shinawatra, 76, were once such close friends that they reportedly called one another brothers. Hun Sen has, over the years, supported Thaksin’s family during their long-running power struggle with Thailand’s military. Thaksin and his sister Yingluck stayed

Kemal Ozdemir looked up at the bare peaks of Mount Cilo in Turkey’s Kurdish majority southeast. “There were glaciers 10 years ago,” he recalled under a cloudless sky. A mountain guide for 15 years, Ozdemir then turned toward the torrent carrying dozens of blocks of ice below a slope covered with grass and rocks — a sign of glacier loss being exacerbated by global warming. “You can see that there are quite a few pieces of glacier in the water right now ... the reason why the waterfalls flow lushly actually shows us how fast the ice is melting,” he said.

RESTRUCTURE: Myanmar’s military has ended emergency rule and announced plans for elections in December, but critics said the move aims to entrench junta control Myanmar’s military government announced on Thursday that it was ending the state of emergency declared after it seized power in 2021 and would restructure administrative bodies to prepare for the new election at the end of the year. However, the polls planned for an unspecified date in December face serious obstacles, including a civil war raging over most of the country and pledges by opponents of the military rule to derail the election because they believe it can be neither free nor fair. Under the restructuring, Myanmar’s junta chief Min Aung Hlaing is giving up two posts, but would stay at the