The midday sun turns the dusty streets of the Iraqi frontier town of al-Qaim into a furnace with a heat that keeps many people indoors but fails to deter the man on whom a fragile peace seems to depend.

Wearing a saffron-colored shirt, a 16-shot Beretta strapped to his hip and his head shaved in the style of Yul Brynner, Abu Ahmed patrols al-Qaim in a new Japanese all-terrain vehicle, surrounded by bodyguards toting assault rifles.

“The law here is the law of the tribes,” he said. “The rule of the tribes is stronger than that of Baghdad.”

Abu Ahmed belongs to the Bou Mahal, the most powerful clan in this isolated region of Iraq, some 400km northwest of the capital.

Exclusively Sunni, the tribe controls the nearby frontier with Syria — a kingdom for those who smuggle cigarettes, fuel and weapons.

“We are ready to respect the law of Baghdad, but the government has to represent the people,” he said in a scarcely veiled criticism of the central power, dominated by Shiites.

This reticence to acknowledge the state as the legitimate center of authority and power illustrates the fragility of a nation in which people prefer to put their trust in the hands of men like Abu Ahmed.

The 40-year-old is a hero to the 50,000 residents of al-Qaim for having chased al-Qaeda from the agricultural center where houses line the green and blue waters of the Euphrates.

In the main street, with its fruit and vegetable stalls, its workshops and restaurants, men with pistols in their belts approach Abu Ahmed to kiss his cheek and right shoulder in a mark of respect.

It was not always this way.

He tells how one evening in May 2005 he decided that the disciples of Osama bin Laden went too far — they killed his cousin Jamaa Mahal.

“I started shooting in the air and throughout the town bursts of gunfire echoed across the sky. My family understood that the time had come. And we started the war against al-Qaeda,” he said.

It took three battles in the streets of al-Qaim — in June, in July and then in November of that year — to finish off the extremists who had come from Arab countries to fight the Americans.

Abu Ahmed, initially defeated by better-equipped forces, had to flee to the desert region of Akashat, around 100km southwest of Al-Qaim. There he sought help from the US Marines.

“With their help we were able to liberate al-Qaim,” he said, sitting in his house with its maroon tiled facade.

This alliance between a Sunni tribe and US troops was to be the first, and it give birth to a strategy of other US-paid Sunni fighters ready to mobilize against al-Qaeda. It resulted in the Sunni province of al-Anbar being pacified in two years.

The US military, which since it led the spring 2003 invasion of Iraq had sought to control the frontier with Syria, found in the men of Abu Ahmed an auxiliary force completely au fait with all the routes used by the smugglers.

And while Abu Ahmed has been able to receive the homage and rewards, which are seen as his right as a warlord, he is very aware that the current calm is a fragile one.

“I’ve drawn up my will several times,” he said. “I expect to die.”

His town had an unhealthy reputation for years, and no Westerners other than US troops risked going there.

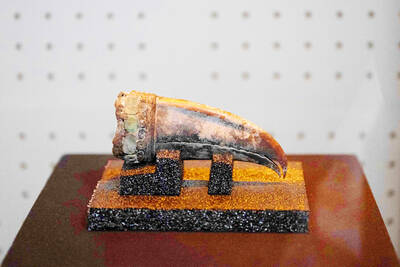

In the era of former Iraqi president Saddam Hussein, al-Qaim’s huge chemical factory treated uranium to feed Iraq’s nuclear program. But US air strikes in 1991 and then UN inspections transformed the factory into a metallic skeleton. Its destruction buried the town’s only source of income.

And al-Qaeda killers are still never far away. Recently men disguised as US soldiers approached a post near the frontier with Syria. Police manning it trustingly handed over their weapons.

The disarmed men were then forced to their knees and 16 of them had their throats cut.

Just one survived to tell the tale of what had happened to his comrades in west Iraq where law and order does not always rule — despite the presence of men like Abu Ahmed.

Archeologists in Peru on Thursday said they found the 5,000-year-old remains of a noblewoman at the sacred city of Caral, revealing the important role played by women in the oldest center of civilization in the Americas. “What has been discovered corresponds to a woman who apparently had elevated status, an elite woman,” archeologist David Palomino said. The mummy was found in Aspero, a sacred site within the city of Caral that was a garbage dump for more than 30 years until becoming an archeological site in the 1990s. Palomino said the carefully preserved remains, dating to 3,000BC, contained skin, part of the

‘WATER WARFARE’: A Pakistani official called India’s suspension of a 65-year-old treaty on the sharing of waters from the Indus River ‘a cowardly, illegal move’ Pakistan yesterday canceled visas for Indian nationals, closed its airspace for all Indian-owned or operated airlines, and suspended all trade with India, including to and from any third country. The retaliatory measures follow India’s decision to suspend visas for Pakistani nationals in the aftermath of a deadly attack by shooters in Kashmir that killed 26 people, mostly tourists. The rare attack on civilians shocked and outraged India and prompted calls for action against their country’s archenemy, Pakistan. New Delhi did not publicly produce evidence connecting the attack to its neighbor, but said it had “cross-border” links to Pakistan. Pakistan denied any connection to

TRUMP EFFECT: The win capped one of the most dramatic turnarounds in Canadian political history after the Conservatives had led the Liberals by more than 20 points Canadian Prime Minister Mark Carney yesterday pledged to win US President Donald Trump’s trade war after winning Canada’s election and leading his Liberal Party to another term in power. Following a campaign dominated by Trump’s tariffs and annexation threats, Carney promised to chart “a new path forward” in a world “fundamentally changed” by a US that is newly hostile to free trade. “We are over the shock of the American betrayal, but we should never forget the lessons,” said Carney, who led the central banks of Canada and the UK before entering politics earlier this year. “We will win this trade war and

Armed with 4,000 eggs and a truckload of sugar and cream, French pastry chefs on Wednesday completed a 121.8m-long strawberry cake that they have claimed is the world’s longest ever made. Youssef El Gatou brought together 20 chefs to make the 1.2 tonne masterpiece that took a week to complete and was set out on tables in an ice rink in the Paris suburb town of Argenteuil for residents to inspect. The effort overtook a 100.48m-long strawberry cake made in the Italian town of San Mauro Torinese in 2019. El Gatou’s cake also used 350kg of strawberries, 150kg of sugar and 415kg of