In the autumn of 1977, as relative calm returned to China after the decade-long chaos of the Cultural Revolution, An Ping was laboring in the countryside where she had been sent, like millions of other young people from the cities, to learn from the peasants.

For two years An, an army general's daughter, fed pigs and chickens and tended crops on a commune outside Beijing, while living in unheated dormitories and going hungry.

Though Mao Zedong (

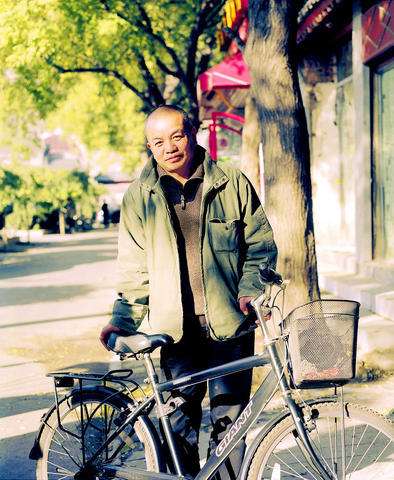

PHOTO: NY TIMES

"For the first time I felt life was not worth it," said An, who was 19 then. "If you had asked me to go on living this kind of life, I would rather die."

Then, in late October 1977, village authorities relayed the news that China would hold its first nationwide university entrance examination since 1965, shortly before academic pursuits were subordinated to political struggle. In acknowledgment of more than a decade of missed opportunity, candidates ranging in age from 13 to 37 were allowed to take the exam.

For An and a whole generation consigned to the countryside, it was the first chance to escape what seemed like a life sentence of tedium and hardship.

A pent-up reservoir of talent and ambition was released as 5.7 million people took the two-day exam in November and December 1977, in what may have been the most competitive scholastic test in modern Chinese history.

The 4.7 percent of test-takers who won admission to universities -- 273,000 people -- became known as the class of 1977, widely regarded in China as the best and brightest of their time.

By comparison, 58 percent of the 9 million exam-takers last year won admission to universities, as educational opportunities have greatly expanded.

Now, three decades later, the powerful combination of intellect and determination has taken many in this elite group to the top in such fields as politics, education, art and business.

Last October, one successful applicant who had gone on to study law and economics at Peking University, Li Keqiang (李克強), was brought into the Chinese Communist Party's decision-making Politburo Standing Committee, where he is being watched as a possible successor to President Hu Jintao (胡錦濤) or Prime Minister Wen Jiabao (溫家寶).

"They were a very bright bunch and they knew it," said Robin Munro, research director for the Hong Kong-based China Labor Bulletin, who was a British exchange student at Peking University in 1978, when those freshmen arrived. "They were the first students in 10 years let into university on merit -- and they were going places."

But back in 1977, most had only a few desperate weeks to prepare for the examination that would change their lives. The timing was especially daunting for those who had been cut off from schooling for years. All over China, students found themselves scrambling to find textbooks, seeking out former tutors and straining to recall half-forgotten formulas.

An, who now works in New York as the director of public relations for Committee of 100, a Chinese-American advocacy group, exaggerated the seriousness of a back injury and took a month's medical leave, which she devoted to studying.

"I had to succeed," she said.

The examination tested not only academic subjects, but also political correctness.

Han Ximing, now 50 and a Chinese literature professor at Nanjing Audit University, said she felt she was already well prepared to handle political questions from careful study of the party line in official newspapers in rural Jiangsu Province.

For years, the papers had been filled with scathing criticism of Deng Xiaoping (

"That was a big topic," she said. "Actually, I had no idea why Deng was supposed to be so bad."

In reality, it was the return of Deng, the veteran Communist leader, to a position of power in Beijing after the fall of the Gang of Four that led to the reinstatement of the annual exam and a return to the pragmatism that would soon ignite decades of explosive economic growth.

Among those who have assumed positions of power, aside from Li of the Politburo, are Zhou Qiang (

Artistic talent to emerge from the class of 1977 includes the filmmakers Zhang Yimou (

"To be immodest, it was a phenomenal generation," said Fan Haoyi, now 50, who earned a chance to study French at the Beijing Institute of Foreign Languages (now the Beijing Foreign Studies University), a stepping stone to a business career in Africa and Europe. "We had a rage to learn."

Many successful candidates said they felt they had been given a priceless opportunity and were determined to make the most of it.

"We were not just gifted, we also worked really hard," Han said.

Still, not everyone jumped at the chance to take the exam.

After years when privilege and opportunity were reserved for the offspring of senior officials or people with approved class backgrounds, many prospective candidates doubted that the test would be fair. Others were reluctant to give up the security of even menial jobs.

For An, the desire to escape her rural life was tempered by the conviction that taking the exam was risky. Relations between the farmers and students were complex; if she failed and was forced to return to the village, she worried that she would be given all the dirty jobs.

"They didn't like us being there because they had to share their land," she said. "But if we tried to leave, they would think we looked down on them."

Li Xiyue was also part of a rural production team. The work was hard but he found it difficult to imagine any other future for himself.

"By the time I was sent to the rural areas, this policy had been in place for 10 years," said Li, 50, who won a seat at Guangxi University and went on to become a writer and university lecturer.

Hard farm labor "was normal," he said. "Going to college was not normal."

Still, he found time to study in his spare time.

"The problem was, it was difficult to find interesting material," he said. "I would even read the literature that came with farming equipment."

When the time came to take the university entrance exam, some found it difficult to break with the commune.

Han was allowed to return home to study for the exam, but she became alarmed when she heard that she had been criticized at a commune meeting for pursuing personal ambition at the expense of the revolution.

"I ran back to the team, but my father was very angry and brought me home," she said. "He banned all further contact with them."

An said she had taken some French in middle school, but classes were overlaid with politics and broken up by military training and factory work. Less than confident, she went to see a former teacher who assured her that the examiners would not ask overly complicated questions.

But the teacher predicted that she would be asked why she wanted to study French, advising her to say she was doing it to serve the revolution.

"They did ask me that," said An, who qualified to study French at the Beijing Language Institute (now the Beijing Language and Culture University) and later at the Sorbonne in Paris.

When the academic year began in 1978, after the lost decade of the Cultural Revolution, it was an unusually mature freshman class that entered universities across the country. Han said that some of her fellow students at Nanjing Normal University were twice her age.

"I had a classmate who was the father of four kids," she said.

As they began their studies, many were fired by idealism and eagerness to achieve a fresh start for themselves and their country.

"It was a time full of dreams and hopes for the future," Han said.

Thirty years later, many express mixed feelings about the direction events took. While acknowledging the benefits of China's economic development, some voiced disappointment with the pace of political change.

"A lot of things we could not even imagine have become reality," Li Xiyue said. "But it's painful to see so much corruption, especially among high-ranking officials."

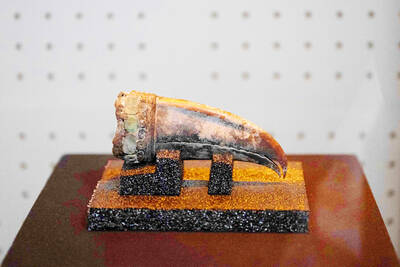

Archeologists in Peru on Thursday said they found the 5,000-year-old remains of a noblewoman at the sacred city of Caral, revealing the important role played by women in the oldest center of civilization in the Americas. “What has been discovered corresponds to a woman who apparently had elevated status, an elite woman,” archeologist David Palomino said. The mummy was found in Aspero, a sacred site within the city of Caral that was a garbage dump for more than 30 years until becoming an archeological site in the 1990s. Palomino said the carefully preserved remains, dating to 3,000BC, contained skin, part of the

‘WATER WARFARE’: A Pakistani official called India’s suspension of a 65-year-old treaty on the sharing of waters from the Indus River ‘a cowardly, illegal move’ Pakistan yesterday canceled visas for Indian nationals, closed its airspace for all Indian-owned or operated airlines, and suspended all trade with India, including to and from any third country. The retaliatory measures follow India’s decision to suspend visas for Pakistani nationals in the aftermath of a deadly attack by shooters in Kashmir that killed 26 people, mostly tourists. The rare attack on civilians shocked and outraged India and prompted calls for action against their country’s archenemy, Pakistan. New Delhi did not publicly produce evidence connecting the attack to its neighbor, but said it had “cross-border” links to Pakistan. Pakistan denied any connection to

TRUMP EFFECT: The win capped one of the most dramatic turnarounds in Canadian political history after the Conservatives had led the Liberals by more than 20 points Canadian Prime Minister Mark Carney yesterday pledged to win US President Donald Trump’s trade war after winning Canada’s election and leading his Liberal Party to another term in power. Following a campaign dominated by Trump’s tariffs and annexation threats, Carney promised to chart “a new path forward” in a world “fundamentally changed” by a US that is newly hostile to free trade. “We are over the shock of the American betrayal, but we should never forget the lessons,” said Carney, who led the central banks of Canada and the UK before entering politics earlier this year. “We will win this trade war and

Armed with 4,000 eggs and a truckload of sugar and cream, French pastry chefs on Wednesday completed a 121.8m-long strawberry cake that they have claimed is the world’s longest ever made. Youssef El Gatou brought together 20 chefs to make the 1.2 tonne masterpiece that took a week to complete and was set out on tables in an ice rink in the Paris suburb town of Argenteuil for residents to inspect. The effort overtook a 100.48m-long strawberry cake made in the Italian town of San Mauro Torinese in 2019. El Gatou’s cake also used 350kg of strawberries, 150kg of sugar and 415kg of