Anthropologists are not often giddy with excitement, but the unearthing of the skeleton of a meter-tall female who hunted pygmy elephants and giant rats 18,000 years ago has them whooping with delight the finding of another piece of the puzzle of the origin of the species.

The finding on a remote eastern Indonesian island has stunned anthropologists like no other in recent memory and could rewrite the history of human evolution.

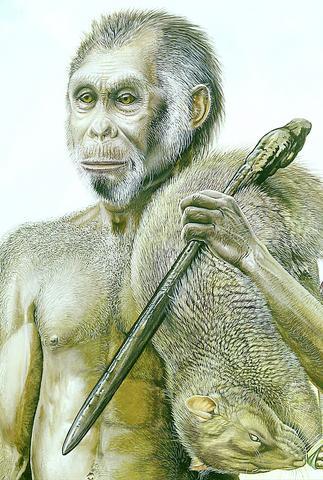

PHOTO: AFP/COURTESY OF ARTIST PETER SCHOUTEN/NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC

Affectionately called Hobbit, Homo floresiensis was found on the floor of a limestone cave on the island of Flores by Australian scientists working with their Indonesian counterparts.

"This is one of the most astonishing discoveries I've seen in my lifetime," bubbled Tim Flannery, South Australia Museum director.

"To imagine that just 12,000 years ago you could have gone to the island of Flores and seen these tiny little creatures less than 1 meter high and weighing 16 kilograms living there is just amazing," he said.

The discover smashes the long-cherished scientific belief that our species, Homo sapiens, systematically crowded out other upright-walking human cousins beginning 160,000 years ago and that we've had Earth to ourselves for tens of thousands of years.

Instead, it suggests recent evolution was more complex than previously thought. And it demonstrates that Africa, the acknowledged cradle of humanity, does not hold all the answers to persistent questions of how -- and where -- we came to be.

Scientists called the dwarf skeleton "the most extreme" figure to be included in the extended human family. Certainly, she is the shortest.

She is the best example of a trove of fragmented bones that account for as many as seven of these primitive individuals that lived on Flores. The mostly intact female skeleton was found in September last year. Details of the discovery appear in yesterday's issue of the journal Nature.

The specimens' ages range from 95,000 to 12,000 years old, meaning they lived until the threshold of recorded human history and perhaps crossed paths with the ancestors of today's islanders.

"The find is startling," said Robert Foley of Cambridge University. "It's breathtaking to think that another species of hominin existed so recently."

What puzzles scientists is that Homo floresiensis was able to do so much with so little brain power.

Mike Morwood, the University of New England anthropology professor who co-led the Flores team, reckoned that with a brain of just 380cm3 the hairy little people of Flores "would have been flat out chewing grass and nuts."

But they were accomplishing much more than that. Morwood believes the proto humans sailed to the island. He points to the evidence that they made primitive tools, hunted pygmy elephants called stegodons and cooked their meat and that of giant rats.

"Language is a given," Morwood said, reasoning that hunting would require at least a primitive form of communication because their elephant prey were up to 500kg and more than a match for one hunter.

He sees Flores as something of a "lost world" isolated from evolutionary currents. It's a view that leads others to suggest that other islands in Indonesia might harvest other primitive human species.

"My suspicion is that there will be many more examples of pygmy humans," Flannery said.

Homo floresiensis is the smallest human ever found. And, since the discovery of Neanderthal remains in Europe 200 years ago, Homo floresiensis is the first new species.

We don't know yet what happened to the little people of Flores but one possibility is that they were wiped out during a volcanic eruption. Flannery believes the likely answer is that the pygmy people were despatched by a later line of Homo erectus, the Homo sapiens.

‘TERRORIST ATTACK’: The convoy of Brigadier General Hamdi Shukri resulted in the ‘martyrdom of five of our armed forces,’ the Presidential Leadership Council said A blast targeting the convoy of a Saudi Arabian-backed armed group killed five in Yemen’s southern city of Aden and injured the commander of the government-allied unit, officials said on Wednesday. “The treacherous terrorist attack targeting the convoy of Brigadier General Hamdi Shukri, commander of the Second Giants Brigade, resulted in the martyrdom of five of our armed forces heroes and the injury of three others,” Yemen’s Saudi Arabia-backed Presidential Leadership Council said in a statement published by Yemeni news agency Saba. A security source told reporters that a car bomb on the side of the road in the Ja’awla area in

‘SHOCK TACTIC’: The dismissal of Yang mirrors past cases such as Jang Song-thaek, Kim’s uncle, who was executed after being accused of plotting to overthrow his nephew North Korean leader Kim Jong-un has fired his vice premier, compared him to a goat and railed against “incompetent” officials, state media reported yesterday, in a rare and very public broadside against apparatchiks at the opening of a critical factory. Vice Premier Yang Sung-ho was sacked “on the spot,” the state-run Korean Central News Agency said, in a speech in which Kim attacked “irresponsible, rude and incompetent leading officials.” “Please, comrade vice premier, resign by yourself when you can do it on your own before it is too late,” Kim reportedly said. “He is ineligible for an important duty. Put simply, it was

SCAM CLAMPDOWN: About 130 South Korean scam suspects have been sent home since October last year, and 60 more are still waiting for repatriation Dozens of South Koreans allegedly involved in online scams in Cambodia were yesterday returned to South Korea to face investigations in what was the largest group repatriation of Korean criminal suspects from abroad. The 73 South Korean suspects allegedly scammed fellow Koreans out of 48.6 billion won (US$33 million), South Korea said. Upon arrival in South Korea’s Incheon International Airport aboard a chartered plane, the suspects — 65 men and eight women — were sent to police stations. Local TV footage showed the suspects, in handcuffs and wearing masks, being escorted by police officers and boarding buses. They were among about 260 South

A former flight attendant for a Canadian airline posed as a commercial pilot and as a current flight attendant to obtain hundreds of free flights from US airlines, authorities said on Tuesday. Dallas Pokornik, 33, of Toronto, was arrested in Panama after being indicted on wire fraud charges in US federal court in Hawaii in October last year. He pleaded not guilty on Tuesday following his extradition to the US. Pokornik was a flight attendant for a Toronto-based airline from 2017 to 2019, then used fake employee identification from that carrier to obtain tickets reserved for pilots and flight attendants on three other