Kristina tapped the veins on top of her right foot and plunged in a syringe filled with cloudy fluid, slowly pressing the stopper down to deliver her dose of heroin.

"I'm home," the 29-year-old prostitute said, leaning back to let the high course through her emaciated body, satisfying the craving she's nurtured as a drug addict for eight years. The cost: the equivalent of US$2.60.

This scene in a dingy backroom in the capital Ashgabat isn't happening -- at least not according to the authoritarian government of this Central Asian nation. Since 2000, Turkmenistan has failed to report any drug seizures to international organizations and President Saparmurat Niyazov has claimed the country -- next door to Afghanistan, source of most of the world's opium -- has no drug problem.

But like much in Turkmenistan, behind the new marble buildings of what Niyazov has proclaimed the country's "Golden Century" lies a reality little touched by government riches, where drug dealers and addicts roam potholed streets lined with dilapidated houses.

Does the former Soviet republic have a drug problem?

"We have no problem -- you can go into any house and find heroin," said Kristina, the name she gives clients who find her every night on a central Ashgabat street for US$10 an hour.

Some estimates say as many as half of all Turkmen men aged 15 to 40 use heroin or opium. The country's borders with Afghanistan and Iran, another major drug transit country, are loosely controlled on both sides, if at all.

Turkmen authorities "believe there are no seizures because there is no trafficking," Antonio Maria Costa, head of the UN Office on Drugs and Crime, said during a recent tour of Central Asia. "I would like to be reassured that's the case."

Any estimate of drug traffic or addiction is simply a guess as long as the government doesn't publicize statistics -- partly because of officials' fears of releasing any bad news that might displease Niyazov. President since 1985, Niyazov regularly fires ministers and bureaucrats in what analysts say is a means to prevent any possible opposition to his one-man rule.

However, there are some signs the government's head-in-the-sand policy on drugs is changing. It has accepted a new UN project funded by the US that aims to give US$1.1 million in equipment and training for border guards to help stop drug trafficking, and foreign diplomats have recently been allowed more open access to assess the frontier.

Turkmen border guards also recently were allowed to travel to the US for training and the US Drug Enforcement Agency conducted a seminar for them.

"It's small steps, but it's steps in the right direction," a western ambassador in Ashgabat said on condition of anonymity.

"They are concerned but do not recognize the extent" of the drug problem, said Paraschiva Badescu, the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe's ambassador to Turkmenistan. "They're not ready to discuss the causes of drug consumption."

The level of government control over every aspect of life here has led some exiled opposition critics to accuse the regime -- up to the president himself -- of involvement in drug trafficking. No proof of such a connection has ever been documented.

Drug addicts say they are afraid to seek treatment from authorities for fear of being shipped to work camps where doctors and nurses meant to be treating their addiction actually fuel their habit to make money.

One 31-year-old former addict, who spoke on condition of anonymity, said he was introduced to opium while serving a five-year prison sentence for assault. He quit when he was released from prison, but then started again after coming to live in Ashgabat, which he said was awash in drugs. The addict quit cold four years ago, telling himself "either I'll die or go to jail."

Kristina said she was introduced to drugs by her husband, whose bank salary allowed him to indulge. He eventually lost his job, and sold their apartment and car to get money to support the habit.

When that money ran out four years ago, Kristina started working as a prostitute, seeing clients in one room while her husband waited for the money in the bathroom.

Kristina avoids a city AIDS center where she could get syringes for free, saying the employees would turn her in for being an addict. She buys them instead at a drug store, using each twice and insisting she doesn't share needles.

At age 25, Kristina was sent to prison for two years on drug charges. She was jailed again in April for prostitution but said authorities released her after two weeks, when she started showing withdrawal symptoms and they feared she would die in custody.

Despite her ordeal, Kristina said she has no desire to give up drugs.

"I don't want to stop, I live for heroin now. I have no other life," she said.

Indonesia yesterday began enforcing its newly ratified penal code, replacing a Dutch-era criminal law that had governed the country for more than 80 years and marking a major shift in its legal landscape. Since proclaiming independence in 1945, the Southeast Asian country had continued to operate under a colonial framework widely criticized as outdated and misaligned with Indonesia’s social values. Efforts to revise the code stalled for decades as lawmakers debated how to balance human rights, religious norms and local traditions in the world’s most populous Muslim-majority nation. The 345-page Indonesian Penal Code, known as the KUHP, was passed in 2022. It

‘DISRESPECTFUL’: Katie Miller, the wife of Trump’s most influential adviser, drew ire by posting an image of Greenland in the colors of the US flag, captioning it ‘SOON’ US President Donald Trump on Sunday doubled down on his claim that Greenland should become part of the US, despite calls by the Danish prime minister to stop “threatening” the territory. Washington’s military intervention in Venezuela has reignited fears for Greenland, which Trump has repeatedly said he wants to annex, given its strategic location in the arctic. While aboard Air Force One en route to Washington, Trump reiterated the goal. “We need Greenland from the standpoint of national security, and Denmark is not going to be able to do it,” he said in response to a reporter’s question. “We’ll worry about Greenland in

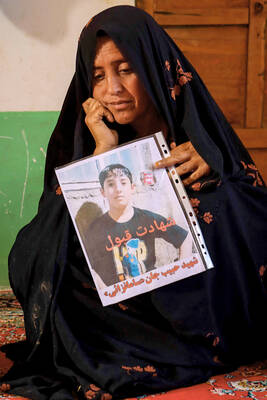

PERILOUS JOURNEY: Over just a matter of days last month, about 1,600 Afghans who were at risk of perishing due to the cold weather were rescued in the mountains Habibullah set off from his home in western Afghanistan determined to find work in Iran, only for the 15-year-old to freeze to death while walking across the mountainous frontier. “He was forced to go, to bring food for the family,” his mother, Mah Jan, said at her mud home in Ghunjan village. “We have no food to eat, we have no clothes to wear. The house in which I live has no electricity, no water. I have no proper window, nothing to burn for heating,” she added, clutching a photograph of her son. Habibullah was one of at least 18 migrants who died

Russia early yesterday bombarded Ukraine, killing two people in the Kyiv region, authorities said on the eve of a diplomatic summit in France. A nationwide siren was issued just after midnight, while Ukraine’s military said air defenses were operating in several places. In the capital, a private medical facility caught fire as a result of the Russian strikes, killing one person and wounding three others, the State Emergency Service of Kyiv said. It released images of rescuers removing people on stretchers from a gutted building. Another pre-dawn attack on the neighboring city of Fastiv killed one man in his 70s, Kyiv Governor Mykola