The Taiwan Fund for Children and Families (TFCF) recently published statistics showing that children between 11 and 15 received a total of almost NT$10 billion in gift money over the Lunar New Year.

This survey used questionnaires that were completed by 1,367 students from elementary and junior high schools.

Up to 94 percent of children receive red envelopes, in which parents put gift money, at Lunar New Year. On ave-rage, each child receives NT$6,274. The Ministry of Education’s statistics for 2009 state that there are 1.54 million students between 11 and 15 years old in Taiwan, so the total amount of gift money they received should be almost NT$10 billion!

Photo: Su Fu-nan, LIBERTY TIMES 照片:自由時報記者蘇福男

About 80 percent of these children choose to save it. Hsiao Ru, a girl attending first year at junior high school, said, “I will save a part of my gift money, and spend the other part on books, game software, or anything else I fancy.” Hsiao Chi, a girl in her sixth year in elementary school, said, “I give all my gift money to my mother. She will save it toward my future school fees. Part of it, combined with another part from my younger sister, is used to sponsor a little girl in another country.”

The TFCF said that parents should teach children the right way to use money, and how to differentiate between the goods they need and those they want. By spending their money on what they need and saving the remainder, they could learn to share what they have and understand the concept of donation. Encouraging children to donate to others of the same age who are in difficulty will teach them to use their money in better ways.

The TFCF suggests that parents should not ask their children to save all their gift money. Instead, they should train them to think about how to manage their money while they use it, and make an appropriate plan for the money they receive, the fund said.

(LIBERTY TIMES, TRANSLATED BY TAIJING WU)

家扶基金會近日針對台灣一千三百六十七位國中及國小學童進行「壓歲錢與零用錢」問卷調查發現,全台灣十一至十五歲的孩子過年領到的壓歲錢總共將近一百億!

高達九成四的孩子在過年時可以領到壓歲錢,平均每個孩子可領到新台幣六千兩百七十四元,若以教育部二零零九年公布的一百五十四萬人計算,十一至十五歲學童的過年壓歲錢總和近新台幣一百億元!壓歲錢的用途,以儲蓄佔八成居多。

就讀國一的小如說:「我的壓歲錢一部分會存起來,一部分會拿來買書、遊戲軟體或自己想要的東西。」讀小六的小琪則說:「我的壓歲錢都會交給媽媽,媽媽會幫我把大部分的壓歲錢存起來當以後的學費,有一部分則是和妹妹一起拿來捐助認養國外的小女孩。」

家扶基金會呼籲,家長應教導孩子學習正確的金錢使用觀念,分辨究竟是「需要」或「想要」。在儲蓄及必要花費之外,也可以適時地將「捐款分享」的觀念帶進生活學習中,藉由誘導孩子幫助同齡的貧困弱勢孩子,讓孩子對金錢的運用及價值有更好的認識。

家扶基金會建議,家長不應一味地要求孩子把所有零用錢或壓歲錢存起來,而是應訓練孩子在使用金錢的過程中花點思考力,將所獲得的金錢做妥善的規劃安排。

(自由時報記者湯佳玲)

For many introverts, shy individuals and people with social anxiety, mingling at parties is often draining or arouses uncomfortable emotions. The internal debate about whether or not to attend large get-togethers can get especially intense during the holiday season, a time when many workplaces celebrate with cocktail hours, gift exchanges and other forms of organized fun. “Some people are just not party people,” City University of New York social work professor Laura MacLeod said. “With a workplace holiday party, there’s a pressure to be very happy and excited. It’s the end of the year, it’s the holidays, we’re all feeling grand.

A: Wow, US climber Alex Honnold has announced that he’s going to free-climb Taipei 101 on Jan. 24. And the challenge, titled “Skyscraper Live,” will be broadcast worldwide live on Netflix at 9am. B: Oh my goodness, Taipei 101 is the world’s tallest green building. Is he crazy? A: Honnold is actually the climber in the 2019 film “Free Solo” that won an Oscar for best documentary, and was directed by Taiwanese-American Jimmy Chin and his wife. He’s a legendary climber. B: Didn’t Alain Robert, “the French Spiderman,” also attempt to scale Taipei 101 in 2004? A: Yes, but

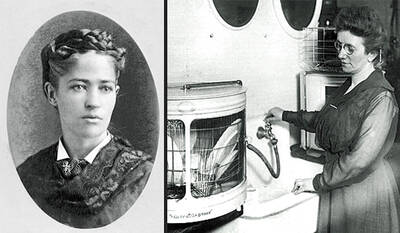

Twelve dinner guests have just left your house, and now a tower of greasy plates stares back at you mockingly. Your hands are already wrinkling as you think about scrubbing each dish by hand. This nightmare bothered households for centuries until inventors in the 19th century tried to solve the problem. The first mechanical dishwashers, created in the 1850s, were wooden machines with hand cranks that splashed water over dishes. Unfortunately, these early devices were unreliable and often damaged delicate items. The real breakthrough came in the 1880s thanks to Josephine Cochrane, a wealthy American socialite. According to her own account,

對話 Dialogue 清清:你看到小陳最近發的滑雪照了嗎?看起來真帥氣。 Qīngqing: Nǐ kàndào Xiǎo Chén zuìjìn fā de huáxuě zhào le ma? Kàn qǐlái zhēn shuàiqì. 華華:感覺滑雪很好玩。看了他的照片以後,我在想要不要去學滑雪。 Huáhua: Gǎnjué huáxuě hěn hǎowán. Kàn le tā de zhàopiàn yǐhòu, wǒ zài xiǎng yào bú yào qù xué huáxuě. 清清:我聽說報名滑雪教室的話,會有教練帶你練習。 Qīngqing: Wǒ tīngshuō bàomíng huáxuě jiàoshì de huà, huì yǒu jiàoliàn dài nǐ liànxí. 華華:可是我有點怕摔倒,而且裝備好像不便宜。 Huáhua: Kěshì wǒ yǒudiǎn pà shuāidǎo, érqiě huāngbèi hǎoxiàng bù piányí. 清清:剛開始一定會摔啊,不過可以先上初級課程,比較安全。 Qīngqing: Gāng kāishǐ yídìng huì shuāi a, búguò kěyǐ xiān shàng chūjí kèchéng, bǐjiào ānquán. 華華:說的也是。那你呢?你想不想一起去? Huáhua: Shuō de yěshì. Nà nǐ ne? Nǐ xiǎng bù xiǎng yìqǐ qù? 清清:我想加一!我們可以先找找看哪裡有教練和適合初學者的課程。 Qīngqing: Wǒ xiǎng jiā yī! Wǒmen kěyǐ xiān zhǎo zhǎo kàn nǎlǐ yǒu jiàoliàn hàn shìhé