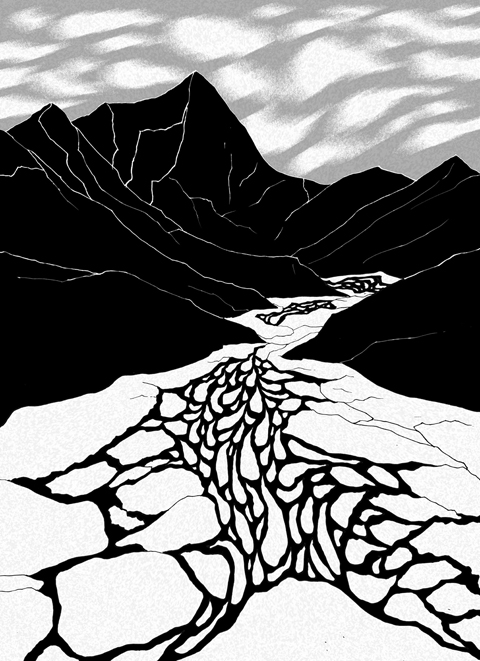

Way above us in the Himalayan cloud are jagged, snowbound peaks — Annapurna, Damodar, Gangapurna, Dhalguri. Below us is the Thulagi glacier, a river of ancient ice snaking steeply down the Marshyangdi valley from near the top of Mount Manasulu.

The small plane banks and skims a lonely pass and we find what we have been looking for: at Thulagi’s snout is a milk-blue lake marked on few maps. It has doubled in size in just a few years and is held back only by a low wall of dead ice and earth. If Thulagi carries on melting at the present rate, nothing will stop billions of liters of water bursting through this natural dam and devastating villages, farmland and everything below.

Thulagi is one of 20 steadily growing glacial lakes in Nepal, which mountain communities and scientists fear will inevitably rupture if the growth in greenhouse gas emissions is not stemmed by world leaders at the Copenhagen climate summit. Average temperatures across Nepal have risen 1.6°C in 50 years — twice the global average. But here on the roof of the world, in what is called the “third pole,” they are already nearly 4°C above normal and on track to rise by as much as 8°C by 2050.

Temperature rises like this in the Himalayas would be a catastrophe. It is not just the future of a few mountain communities at stake but the lives of nearly one in four people in the world, all of whom rely on the Himalayas for water. Nepalese rivers alone provide water for 700 million people in India and Bangladesh.

“If there is less snow in the Himalayas, or the monsoon rains weaken, or the glaciers melt with climate change, then all south Asian farming, industry, water supplies and cities will suffer,” Nepalese climate specialist Ngamindra Dahal said.

On a 1,609km journey from the world’s greatest water source in the Himalayas, down rivers and then by train through Nepal, India and Bangladesh to the Bay of Bengal, we saw evidence of profound changes in weather patterns right across south Asia. Wherever we went we were told of significant temperature increases, and found governments slowly waking up to the threat of climate change and communities having to respond in any way they could to erratic rains and more serious droughts, floods and storms.

The starting point was Jomsom, a small town in the Kali Gandaki valley, 2,300m high and at the heart of the Annapurna range. This remote town, which saw its first ever car last year, has experienced no snowfall this winter. The temperature soared way above normal to 27°C, and only fell to 13°C, against a usual minus 4°C, while the snowline has risen above 5,000m. The Gandaki river, fed by 1,200 glaciers, flows to the Ganges and on to Bangladesh.

“The temperature is higher, so there’s less snow, and less meltwater in spring to plant crops. People have no need to come down from the mountains in winter. They can grow chillies and peppers now,” said Sunil Pant, a Nepalese member of parliament. “But now they cannot grow wheat or staple foods.”

It’s the same story even in the Everest valley region, 644km to the east of Jomsom, where the snowfall is becoming increasingly unpredictable. Already, some communities believe they are a living under a death sentence, according to Lucky Sherpa, the member of parliament for the region.

“They say they are not sure there will be a tomorrow,” she said. “The snow used to come up to your waist in winter. Now children do not know what snow is. We have more flies and mosquitoes, more skin diseases. Communities are adapting by switching crops, but diseases are moving up the mountains, the tea and apple crops are being hurt and wells are drying up.”

Three-hundred and twenty-two kilometers away in Nepal’s capital, Kathmandu, Simon Lucas, a climate change officer at the UK Department for International Development, confirmed that river flows in winter have seriously declined.

“The trends are clearer in Nepal than in other countries,” he said. “People cannot plant their crops in the spring because the winter snows are not so heavy. They have always relied on snow and glacier melt.”

Britain last week earmarked US$81.5 million for Nepal to adapt to climate change, mainly through investing in its forests, but climate scientists say it faces ever more erratic, intense and unpredictable rainfall.

We found the evidence for that when we headed south towards Nepal’s border with Bihar state in India. Here the problem is not too little water but far too much; last year, following torrential monsoon rains, Nepal’s greatest river, the Khosi, broke though 2km of embankment and flooded hundreds of square kilometers of farmland. Nearly 1,500 people died and 3 million people were displaced. Fifty thousand people in Nepal and many more in India lost their homes, and the river changed its course by more than 150km.

The Khosi is known as “the river of sorrow” because it often floods, but the scale of what happened last August shocked both Indian and Nepalese governments. When the waters finally receded, people found vast areas of farmland covered by a 1.8m-deep sea of sand brought down in suspension from the mountains. Seven months on, the embankment has been repaired but people are devastated and everyone is frightened that this kind of flood will become more common.

“It’s impossible to cultivate anything”, said Ashma Khatoum, a farmer. “There are no toilets, or clean drinking water. I don’t believe we will ever get back to normal again.”

We crossed the Indian border and went straight from severe flood to deep drought. Bihar, one of India’s poorest states, is experiencing one of its worst droughts in a generation. This year it has had only 15 percent to 30 percent of its usual rains. Most of the state has been declared a drought zone and 63 million people are expected go hungry next year.

“Climate change is definitely happening,” said Vyas Ji, principal secretary in the department of disaster management in the Bihar state capital, Patna.

“We used to have droughts every four or five years and floods every two to three years. Now it’s very erratic. Even the flood-prone districts are facing drought. Rainfall used to be predictable, limited and beneficial to farmers. Now it is unpredictable, heavier and harmful. Now there is no winter. Farmers are confused,” Ji said.

“This was a rice cultivating state but the seedlings get destroyed,” Ji said.

We headed south again, to Kolkata, one of India’s great cities, which last week was warned again by international scientists that it was acutely vulnerable to sea level rises. Here temperatures have risen significantly and there are more cases of dengue fever and malaria, Kolkata Mayor Bikash Bhattacharya said. “Copenhagen is the last chance that the poor have. If we do not succeed and we go on with business as usual, then the world’s poor people will have a very hard time.”

“Climate change is not the future. It is now. Tens of thousands of Indians are already in a critical situation,” said Sugata Hazra, director of Jadavpur University’s school of oceanography in Kolkata.

His researchers have recorded sea levels in the Bay of Bengal rising far faster than the global average, and more cyclones hammering the coast. The result is the inundation of islands from higher tides and surges.

“The rate of relative sea level rise in the Sagar Islands [in the Indian Sundarbans] is 3.14mm per year, which is substantially more than the global average of 1 to 2mm per year. It is up to 5.2mm in some places. By 2020 at least 70,000 people will have been made homeless,” Hazra said.

Anurag Danda, head of WWF’s Sundarbans delta program, appealed to politicians in Copenhagen for help.

“For the people of the Sundarbans, climate change has arrived. The Maldives gets the attention, but there are many other people facing disaster,” Danda said.

From Kolkata we headed to the Bangladeshi border. There, India is building a 4.6m fence to keep its neighbors out. For the moment those wanting to leave are mainly young men seeking work in the booming Indian economy, but in future, say analysts, it could be climate refugees.

Bangladesh is by far the most densely populated large country in the world and, being entirely on a low-lying delta, it is one of the most vulnerable. It stands to lose 20 percent of its land to sea level rise in the next 80 years and is already experiencing more frequent and more intense cyclones. In the last seven years, four of the most powerful storms ever recorded have slammed its coasts.

Climate change, on top of all its other problems, means Bangladesh faces even deeper problems, said Kim Streatfield, director of the Center for Health and Population Research at ICDDR, an international research institution in Dhaka. He fears the combination of climate change and an expected 50 million to 100 million population rise in the next 50 years will devastate the country unless action is taken.

“Increasing salinity in the water will have a major effect on food production,” he said. “In addition, the water table is dropping 2 to 3 meters a year, and one in four wells can be dry in the dry season.”

Our south Asian climate odyssey from source to sea ended south of Chittagong, on the Bay of Bengal. There, where the waters of the Kali Gandaki, the Ganges and Nepal’s many other rivers reach the ocean, communities are experiencing higher tides and more flooding, as well as the loss of farmland and fishing.

“The sea water now comes right into our houses. We would all like to move, but there is nowhere to go,” said Geeta Das, a teacher in Bolihut village, near Chittagong.

Her home has been partly washed away and her bed is now just a 0.30cm from where the waters reached a few weeks ago.

“We panic when it is cloudy and it is about to rain. We fear we will lose our children,” Das said.

A neighbor, Madhuri Das, said: “We do not need scientists or anyone to tell us things are changing. We know the sea level is rising. We have always lived here. The floods are more frequent and we now fear the sea. Ten years ago, the seawater never came to the village. We cannot afford to raise our houses except on mud, which gets washed away. We can’t use the toilets, and diseases are now more common. Our water is no longer sweet.”

Nurun Nahar, a Bolihut fisherman, gave up his trade when catches declined precipitously three years ago. His experiences speak for the 700 million people who depend on Nepal and the Himalayas for their lives.

“We are poor so we cannot do much to adapt on our own to what we can see is taking place. But we do not want to depend on nature any more. We see so many changes happening. All we want is a secure life. We are resilient but we must look to the rich to help us make this world a better place,” he said.

In their recent op-ed “Trump Should Rein In Taiwan” in Foreign Policy magazine, Christopher Chivvis and Stephen Wertheim argued that the US should pressure President William Lai (賴清德) to “tone it down” to de-escalate tensions in the Taiwan Strait — as if Taiwan’s words are more of a threat to peace than Beijing’s actions. It is an old argument dressed up in new concern: that Washington must rein in Taipei to avoid war. However, this narrative gets it backward. Taiwan is not the problem; China is. Calls for a so-called “grand bargain” with Beijing — where the US pressures Taiwan into concessions

The term “assassin’s mace” originates from Chinese folklore, describing a concealed weapon used by a weaker hero to defeat a stronger adversary with an unexpected strike. In more general military parlance, the concept refers to an asymmetric capability that targets a critical vulnerability of an adversary. China has found its modern equivalent of the assassin’s mace with its high-altitude electromagnetic pulse (HEMP) weapons, which are nuclear warheads detonated at a high altitude, emitting intense electromagnetic radiation capable of disabling and destroying electronics. An assassin’s mace weapon possesses two essential characteristics: strategic surprise and the ability to neutralize a core dependency.

Chinese President and Chinese Communist Party (CCP) Chairman Xi Jinping (習近平) said in a politburo speech late last month that his party must protect the “bottom line” to prevent systemic threats. The tone of his address was grave, revealing deep anxieties about China’s current state of affairs. Essentially, what he worries most about is systemic threats to China’s normal development as a country. The US-China trade war has turned white hot: China’s export orders have plummeted, Chinese firms and enterprises are shutting up shop, and local debt risks are mounting daily, causing China’s economy to flag externally and hemorrhage internally. China’s

During the “426 rally” organized by the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and the Taiwan People’s Party under the slogan “fight green communism, resist dictatorship,” leaders from the two opposition parties framed it as a battle against an allegedly authoritarian administration led by President William Lai (賴清德). While criticism of the government can be a healthy expression of a vibrant, pluralistic society, and protests are quite common in Taiwan, the discourse of the 426 rally nonetheless betrayed troubling signs of collective amnesia. Specifically, the KMT, which imposed 38 years of martial law in Taiwan from 1949 to 1987, has never fully faced its