Detouring south into the busiest part of Taichung City’s Qingshui District (清水區) in search of lunch had been a mistake, I realized soon after I’d finished my noodles. When I pointed my bicycle north and began pedaling, I could feel the strength of the winds blasting across the flat landscape. Covering the six or so kilometers to Gaomei Wetlands (高美濕地) took me more than half an hour.

The wetlands, which lie between the mouth of the Dajia River (大甲溪) and the Port of Taichung (台中港), didn’t exist half a century ago. The building of Gaomei Levee in 1976 led to a rapid accumulation of silt and sand. This, coupled with erosion along the southern shore of the Dajia River estuary, resulted in an expanse of tidal mudflats.

In 2004, Taichung County Government — which merged with Taichung City in 2010 — demarcated 701.3 hectares of dry land and seashore as Gaomei Wildlife Sanctuary (高美野生動物保護區). This area includes the most-visited part of the wetlands near the tiny settlement of Yuliao (魚寮).

Photo: Steven Crook

Regulations governing the sanctuary prohibit the killing, capturing or harassing of wild birds and animals, and outlaws the destruction of their habitats or of wild plants. Neither animals nor plants can be released or introduced without official permission. Development and construction are prohibited, but if habitats of wild creatures are destroyed, the authorities are empowered to establish “necessary habitat improvement, breeding, conservation, and maintenance and release facilities.”

There’s one important exception to all this, however: local fishermen who are registered in the area are allowed to continue fishing. And that’s to say nothing of the pressure on the local environment caused by tourists, of whom there were scores on the weekday I visited. At peak times, there can be hundreds of people on the 500m-long boardwalk or out on the mudflats.

During the cooler months, some people come here to see waterbirds. BirdLife International’s Web site lists Gaomei as an Important Bird Area for two reasons: At least one globally threatened avian species spends time here, and more than 1 percent of at least one species’ global population gathers here on a regular basis.

Photo: Chang Ching-ya, Taipei Times

What’s more, Gaomei has Taiwan’s largest colony of Bolboschoenus planiculmis (a type of sedge), and a dense forest of Australian pine trees. The latter were planted as windbreaks, but have become, according to BirdLife International “excellent bird habitat.”

Nevertheless, in a 2012 blog post, a Taiwan-based professional birdwatching guide described the wetlands as “much abused.”

Given the number of humans around, I wasn’t surprised to see just a few birds. It being low tide, however, the crabs were numerous and active. The area is said to have 30 different cancrine species, and I saw fiddler crabs of different colors emerge from their muddy homes right by the boardwalk. I didn’t spot any mudskippers. Perhaps the mudflats are too exposed for their liking.

Photo: Steven Crook

While I wouldn’t describe the scenery as beautiful, it did make for a pleasant change from the urban lowlands I’d been biking through. When I got to the end of the walkway, I noticed some tourists had taken off their shoes and set off across the tidal flats. The breakers seemed very far away indeed — but when the tide turns, how fast does the water come in?

Returning to dry land, I took a quick look at Gaomei Lighthouse (高美燈塔), the grounds of which are open to the public from 9am to 5pm through the winter, then until 6pm from April to the end of October. In terms of architecture or setting, it’s far from the most interesting lighthouse in the country, but at least I could get out of the wind for a short time.

The visitors center at the southern end of the levee was a disappointment. Apart from a desultory selection of souvenirs and a few posters, there was nothing inside. Unless you want to use the bathroom or buy a coffee, the only reason to stop here is to enjoy the view from the roof. After gazing out over the wetlands and the nearby wind turbines (it’s well known that birds and turbines don’t get along), I turned to face south.

Photo: Steven Crook

A huge and unattractive concrete dome was the most obvious part of the Port of Taichung, less than 3km away. A wonderful thing about Taiwan is that you’re never far from somewhere interesting or even beautiful. The coin has two sides, of course. It’s also hard to escape the industrialization and population density.

The precise opening times of the boardwalk are adjusted according to the tide, but even in winter you can depend on it being open seven days per week, from around 8am until at least 5pm.

If seeing the sunset — which is often stunning — is one of your goals, check the Central Weather Bureau’s (www.cwb.gov.tw) Web site. Look for “Astronomy” on the menu, then choose Taichung in “Central Area” as your location. Between now and the end of this month, the sun will set between 5:11pm and 5:20pm. On the same Web site, if you go to “Fishery” and click on “Tidal Forecast,” you’ll find the high- and low-tide times for Qingshui under “Hsinchu-Lukang Inshore.”

Photo: Steven Crook

Steven Crook has been writing about travel, culture, and business in Taiwan since 1996. He is the co-author of A Culinary History of Taipei: Beyond Pork and Ponlai, and author of Taiwan: The Bradt Travel Guide, the third edition of which has just been published.

Photo: Steven Crook

The Lee (李) family migrated to Taiwan in trickles many decades ago. Born in Myanmar, they are ethnically Chinese and their first language is Yunnanese, from China’s Yunnan Province. Today, they run a cozy little restaurant in Taipei’s student stomping ground, near National Taiwan University (NTU), serving up a daily pre-selected menu that pays homage to their blended Yunnan-Burmese heritage, where lemongrass and curry leaves sit beside century egg and pickled woodear mushrooms. Wu Yun (巫雲) is more akin to a family home that has set up tables and chairs and welcomed strangers to cozy up and share a meal

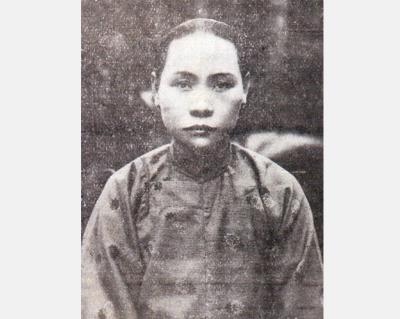

Dec. 8 to Dec. 14 Chang-Lee Te-ho (張李德和) had her father’s words etched into stone as her personal motto: “Even as a woman, you should master at least one art.” She went on to excel in seven — classical poetry, lyrical poetry, calligraphy, painting, music, chess and embroidery — and was also a respected educator, charity organizer and provincial assemblywoman. Among her many monikers was “Poetry Mother” (詩媽). While her father Lee Chao-yuan’s (李昭元) phrasing reflected the social norms of the 1890s, it was relatively progressive for the time. He personally taught Chang-Lee the Chinese classics until she entered public

Last week writer Wei Lingling (魏玲靈) unloaded a remarkably conventional pro-China column in the Wall Street Journal (“From Bush’s Rebuke to Trump’s Whisper: Navigating a Geopolitical Flashpoint,” Dec 2, 2025). Wei alleged that in a phone call, US President Donald Trump advised Japanese Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi not to provoke the People’s Republic of China (PRC) over Taiwan. Wei’s claim was categorically denied by Japanese government sources. Trump’s call to Takaichi, Wei said, was just like the moment in 2003 when former US president George Bush stood next to former Chinese premier Wen Jia-bao (溫家寶) and criticized former president Chen

President William Lai (賴清德) has proposed a NT$1.25 trillion (US$40 billion) special eight-year budget that intends to bolster Taiwan’s national defense, with a “T-Dome” plan to create “an unassailable Taiwan, safeguarded by innovation and technology” as its centerpiece. This is an interesting test for the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT), and how they handle it will likely provide some answers as to where the party currently stands. Naturally, the Lai administration and his Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) are for it, as are the Americans. The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is not. The interests and agendas of those three are clear, but