Sharon Hom (譚競嫦) can’t decide whether to laugh or cringe at how young protesters in Hong Kong, part of her unofficial “fan club,” have turned her into an Internet meme.

The legal academic and executive director of Human Rights in China (HRIC) — a non-government organization based in New York and Hong Kong — has been adjusting to online fame since her forceful defense of Hong Kong’s ongoing protest movement at a US congressional hearing on Sep. 17.

In her testimony, Hom painted a picture of the “David and Goliath” standoff between Hong Kongers and Beijing, detailing China’s rule of law deficits and efforts to discredit the protest movement, as well as the erosion of public confidence in Hong Kong’s administration.

Photo: Davina Tham, Taipei Times

“President Tsai Ing-wen’s (蔡英文) takeaway from the current political crisis in Hong Kong hits the nail on the head,” Hom told the US Congressional-Executive Commission on China. “Not only is ‘one country, two systems’ not a viable model for Taiwan, but the Hong Kong example proves that dictatorship and democracy cannot co-exist.”

On popular online forum LIHKG, Hong Kongers have taken to calling her “Sharon E E,” a romanization of the Cantonese word for “auntie.” The term of endearment captures their affection for Hom, 68, and their perception of her as protector, mentor and friend.

Unlike her comrades, Hom was born but did not grow up in Hong Kong. At the age of five her family left for New York, where today she directs the China and International Human Rights Research Program at the New York University School of Law and serves as Professor of Law Emerita at the City University of New York.

Photo: REUTERS

In town last week for the congress of the International Federation of Human Rights, Hom spoke with the Taipei Times about her views on the endgame for Hong Kong’s protest movement.

IMPERFECT MOVEMENT

Hom’s congressional testimony, targeted at an international audience, struck a chord with many Hong Kongers who lauded it as a fair account of the protest movement. But the message she bears for that movement is one of tough love.

“For the young Hong Kongers, particularly at the front-line, the message they need to hear is: It’s a huge mistake to view mainlanders as a monolithic mass, as an enemy,” Hom says.

In a report by the Central News Agency earlier this month, several Chinese college students in Taiwan said that they supported the protests, but had kept silent about their views for their safety. One Chinese student criticized the “blind patriotism” of her fellow students.

Despite differing views held by some Chinese nationals, there is a growing impression that parts of the protest movement are evolving into a nativist crusade, after incidents in which Chinese immigrants or visitors appeared to be targeted.

Earlier this month, a Mandarin-speaking JPMorgan employee was filmed being punched by a black-clad protester outside the bank’s offices after he had told a gathering crowd, “We are all Chinese.”

In August, protesters at the Hong Kong International Airport restrained two Chinese men, one of whom was a reporter for the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) mouthpiece The Global Times. Images of the incident showed their hands bound with cable ties. Some protesters returned to the airport the next day to express remorse, holding signs that read: “We were desperate and we made imperfect decisions.”

Hom says that the movement is starting to reckon with these complexities. In conversations with protesters, she reminds them of the necessity to look for allies everywhere, even the unexpected places, in order to build a sustainable movement.

“Some of the young activists, I think, are beginning to move to that point of saying, ‘They’re not all our enemies,’” she says.

Such discretion also serves to counter the possibility that continued protests could force Beijing’s hand to take more drastic actions to quell the unrest, as some circumspect observers have warned.

While a majority of protesters are engaged in peaceful demonstration, Hom says “there’s a piece of the movement that is playing into that hand,” and that the movement as a whole will have to decide how to address its more “extreme” elements.

“I think they’re having that conversation now,” she says. “This is why I’m hopeful, because I think they recognize some of the tensions, they recognize some of the conflicts, and they are engaging in it, in a way that I think is so much more nuanced.”

EFFECTIVE EXCHANGE

In the meantime, heightened emotions are spilling over into overseas college campuses, where heated confrontations between students have added to the topography of unrest surrounding the protest movement.

In Australia, Canada, New Zealand and the US, reports of clashes between students from Hong Kong and mainland China and their respective sympathizers have raised alarm about polarization and political influence in schools.

In Taiwan, reports of vandalized “Lennon walls”, which are used to express solidarity with the protesters, and even physical aggression between disagreeing schoolmates have also emerged from college campuses.

Such incidents have prompted a rethink of the notion that moving to a more liberal environment is enough to impress the value of democracy on young people who grew up in China — a mindset that Hom dismisses as the “exchange program mentality.”

“This idea that if you just go, you’re going to absorb something, it’s not true,” she says. “It’s not osmosis, it’s work.”

After the Umbrella Movement, HRIC launched a series of conversations aimed at promoting understanding between young Hong Kongers and mainland Chinese living in Hong Kong.

Hom, who ran legal education exchanges between the US and China for more than a decade, says that the dialogues revealed a lack of socialization between both groups. Since then, she has consistently recommended that exchange programs provide a space for overseas students to discuss and analyze their experiences in their new environment.

“To learn something is work. If you’re exposed to a different culture, you need to process it,” she adds.

‘DEMOCRACY IS INEVITABLE’

Learning is a recurrent theme with Hom, whose years in academia also spanned a two-year Fulbright Scholarship to Beijing in the 1980s. Not long after returning to the US, the Tiananmen Square Massacre took place in June 1989. Her human rights work would later include the Tiananmen Mothers — a human rights group of more than 120 people whose children or relatives were killed in the massacre.

Hom says that Hong Kong Chief Executive Carrie Lam’s (林鄭月娥) strategy for responding to the protest movement has been “a complete page out of... the Communist Party’s playbook,” reminiscent of CCP efforts to “buy off” the Chinese people with economic prosperity after the Tiananmen Square Massacre.

In an annual policy address earlier this month, Lam’s focus on housing and economic measures fueled protesters’ criticisms that she was deaf to their demands for political reform.

This cycle of history repeating itself could inspire cynicism. But Hom remains optimistic about democracy and human rights activists’ ability to learn from past struggles. She traces the hope and steadfastness of today’s protesters back to the “spirit capital” gained during the 2014 Umbrella Movement, and describes the collective decision-making of that earlier movement as “the embryo of a lot of what’s happening now.”

Back in 2004, Hom testified at another congressional hearing on “15 Years After Tiananmen: Is Democracy in China’s Future?” Her answer then was an unequivoval yes: “Democracy is inevitable because the aspirations, hopes, and the willingness to struggle for a more open and democratic China are still powerfully present and alive — against all odds.”

Another 15 years later, Hom says this hasn’t changed.

“[Democracy] is not inevitable in a linear time progression, it’s inevitable because all people really have that aspiration in them,” she says. “It’s just who we are as people.”

On a harsh winter afternoon last month, 2,000 protesters marched and chanted slogans such as “CCP out” and “Korea for Koreans” in Seoul’s popular Gangnam District. Participants — mostly students — wore caps printed with the Chinese characters for “exterminate communism” (滅共) and held banners reading “Heaven will destroy the Chinese Communist Party” (天滅中共). During the march, Park Jun-young, the leader of the protest organizer “Free University,” a conservative youth movement, who was on a hunger strike, collapsed after delivering a speech in sub-zero temperatures and was later hospitalized. Several protesters shaved their heads at the end of the demonstration. A

Google unveiled an artificial intelligence tool Wednesday that its scientists said would help unravel the mysteries of the human genome — and could one day lead to new treatments for diseases. The deep learning model AlphaGenome was hailed by outside researchers as a “breakthrough” that would let scientists study and even simulate the roots of difficult-to-treat genetic diseases. While the first complete map of the human genome in 2003 “gave us the book of life, reading it remained a challenge,” Pushmeet Kohli, vice president of research at Google DeepMind, told journalists. “We have the text,” he said, which is a sequence of

In August of 1949 American journalist Darrell Berrigan toured occupied Formosa and on Aug. 13 published “Should We Grab Formosa?” in the Saturday Evening Post. Berrigan, cataloguing the numerous horrors of corruption and looting the occupying Republic of China (ROC) was inflicting on the locals, advocated outright annexation of Taiwan by the US. He contended the islanders would welcome that. Berrigan also observed that the islanders were planning another revolt, and wrote of their “island nationalism.” The US position on Taiwan was well known there, and islanders, he said, had told him of US official statements that Taiwan had not

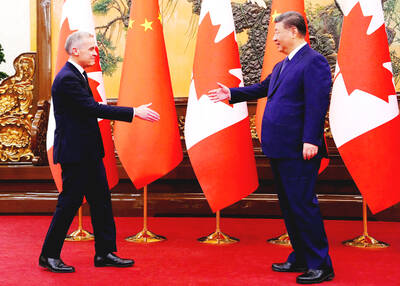

Britain’s Keir Starmer is the latest Western leader to thaw trade ties with China in a shift analysts say is driven by US tariff pressure and unease over US President Donald Trump’s volatile policy playbook. The prime minister’s Beijing visit this week to promote “pragmatic” co-operation comes on the heels of advances from the leaders of Canada, Ireland, France and Finland. Most were making the trip for the first time in years to refresh their partnership with the world’s second-largest economy. “There is a veritable race among European heads of government to meet with (Chinese leader) Xi Jinping (習近平),” said Hosuk Lee-Makiyama, director