CJ Anderson-Wu (吳介禎) is busily engaged in Taiwan’s literary scene, much of the time translating works from English into Chinese. Impossible to Swallow, however, is a collection of her own short stories, advertised as being about the impact of Taiwan’s White Terror on the lives of ordinary people.

The first story, “Judge Not,” is about a group of lawyers working on the political prosecution of a magazine. None of them expresses a particularly strong view, and clearly the prosecution is destined to succeed in precisely the way it was intended to. The journal turns out to be Formosa Magazine, which lay at the center of the famous Formosa Incident, or Kaohsiung Incident, of 1979.

“Blue Eyes” is mostly a dialogue between a mother and her daughter about the daughter’s father, formerly an American serviceman in Taiwan but now out of the picture. The capitulation, as many Taiwanese saw it, of then-US president Jimmy Carter to China in 1979 was the occasion for the departure of US troops from the island.

“First Lady” comes next, and is about the wife of a long-serving Taiwan president on the occasion of his death. Here politics is for the first time in full focus, with contenders for the vacant post easy manipulated by the former first lady.

“Wednesdays” presents the wife of a man who has inexplicably disappeared. On every Wednesday for 17 years she travels to the local detention center in an attempt to discover what has become of him. Eventually one of his former colleagues is released, and says that the man is probably dead. He and several others were detained because they were involved in raising money for a publication in the US advocating Taiwanese democracy.

Next comes “Those Healed and Unhealed,” in which a 90-year-old doctor deals with patients he’s known for half a lifetime, revealing in the process histories of arrest and incarceration on Green Island. It was a time when Chiang Kai-shek’s (蔣介石) policy, one character reminisces, was it was better to punish 99 innocent people than let one guilty one escape.

The title story, “Impossible to Swallow,” follows. It’s set in relatively modern times and concerns an American man working in Taiwan and engaged to be married to a Taiwanese woman. During one conversation between the two the woman recalls the days of censorship, when the Taiwanese language was under deep suspicion. Censorship operates together with fear, distrust and hatred, she says, until your life gradually erodes and becomes “impossible to swallow.”

The two work for an airline company in which a strike is planned over working hours. A more humane schedule is eventually introduced, but as a result the company loses much of its value to investors. That’s capitalism, the American thinks.

“Legacy” is unusual in this volume in having a main character who is gay. He’s involved in street protests under the leadership of his professor, who is eventually arrested and tortured to death. The professor’s mother is a convinced radical and supports the protesters by cooking and selling Korean food under the name “Democratic Kimchi.”

“Others’ Guilt” happens to include an aboriginal character but this isn’t at the heart of the story. It’s about a young boy who acts as a courier, taking food to a man who has fled his home to live in the woods after being accused of being a communist. The people who prepare the food also make a false certificate of identification for the fugitive.

Twenty years later the young boy, now adult and living in Taipei, is accused of murder, while the former fugitive is a senior figure in the prosecutor’s office. It’s possible he could save the accused’s life but he doesn’t, and the man, who was once responsible for saving him, is executed.

The last story, “A Letter from Father,” is extremely short. It simply consists of a letter from an imprisoned father to his daughter. He compares her and her mother to the trees he can see out of his dormitory window, and hopes they will flourish and his daughter grow up straight and strong.

The date is given as March 28, 1982, and an appended note states that it was “inspired by a letter of Tsai Yi-Cheng, who had been incarcerated for 24 years, because of his involvement with underground political activities.”

These stories certainly demonstrate the range of those who suffered under Taiwan’s White Terror, the harsh targeting of perceived political dissidents usually dated as lasting from 1947 to 1987. They also show how different people were affected in different ways, some directly by imprisonment and not infrequently death, others by being their relatives, others involved towards the end of the period in protests that led to less traumatic results.

What characterizes these tales is the absence of scenes of violence. There is none of the brutal assault, including murder and torture, that the White Terror regime was responsible for. Instead, we see the effects of such horrors on other people, with the implication that the atmosphere of repression was pervasive and left few Taiwanese citizens untouched.

Assuming that this was the author’s intention, then the perspective is finely managed, and the comprehensive point well made. And the inclusion of minorities — an Aborigine, a gay and a foreigner — certainly emphasizes the book’s range.

I enjoyed these stories. They may not be great masterpieces, but they have variety and an underlying seriousness of purpose, both features of the best fiction.

Serenity International is a publisher of Taiwanese and other literature, with offices in Taipei and a business registration in Nipomo, California.

Last week the story of the giant illegal crater dug in Kaohsiung’s Meinong District (美濃) emerged into the public consciousness. The site was used for sand and gravel extraction, and then filled with construction waste. Locals referred to it sardonically as the “Meinong Grand Canyon,” according to media reports, because it was 2 hectares in length and 10 meters deep. The land involved included both state-owned and local farm land. Local media said that the site had generated NT$300 million in profits, against fines of a few million and the loss of some excavators. OFFICIAL CORRUPTION? The site had been seized

Next week, candidates will officially register to run for chair of the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT). By the end of Friday, we will know who has registered for the Oct. 18 election. The number of declared candidates has been fluctuating daily. Some candidates registering may be disqualified, so the final list may be in flux for weeks. The list of likely candidates ranges from deep blue to deeper blue to deepest blue, bordering on red (pro-Chinese Communist Party, CCP). Unless current Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫) can be convinced to run for re-election, the party looks likely to shift towards more hardline

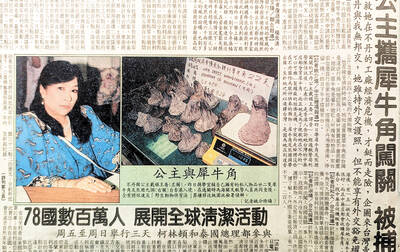

Sept. 15 to Sept. 21 A Bhutanese princess caught at Taoyuan Airport with 22 rhino horns — worth about NT$31 million today — might have been just another curious front-page story. But the Sept. 17, 1993 incident came at a sensitive moment. Taiwan, dubbed “Die-wan” by the British conservationist group Environmental Investigation Agency (EIA), was under international fire for being a major hub for rhino horn. Just 10 days earlier, US secretary of the interior Bruce Babbitt had recommended sanctions against Taiwan for its “failure to end its participation in rhinoceros horn trade.” Even though Taiwan had restricted imports since 1985 and enacted

The depressing numbers continue to pile up, like casualty lists after a lost battle. This week, after the government announced the 19th straight month of population decline, the Ministry of the Interior said that Taiwan is expected to lose 6.67 million workers in two waves of retirement over the next 15 years. According to the Ministry of Labor (MOL), Taiwan has a workforce of 11.6 million (as of July). The over-15 population was 20.244 million last year. EARLY RETIREMENT Early retirement is going to make these waves a tsunami. According to the Directorate General of Budget Accounting and Statistics (DGBAS), the