Feb. 18 to Feb. 24

Until 1985, Taiwan’s amateur (ham) radio scene consisted of one person: Tim Chen (陳實忻), who held the country’s only license due to Martial Law era restrictions. According to a Liberty Times (the sister newspaper of the Taipei Times) report, this resulted in the unusual situation where Taiwan Garrison Command had to establish a set of amateur radio regulations just for him.

Since there was nobody else in Taiwan to talk to, Chen connected with people around the world, using Morse code at first via his station BV2A, and gaining voice communication capabilities in 1974 through BV2B. Chen was strictly forbidden to speak with anyone in China or the Soviet Union, but he enjoyed much popularity as the world’s only BV (Taiwan’s country code) station operator — so much so that US senator and fellow ham enthusiast Barry Goldwater specifically requested to tour Chen’s two stations when he visited Taiwan in 1986.

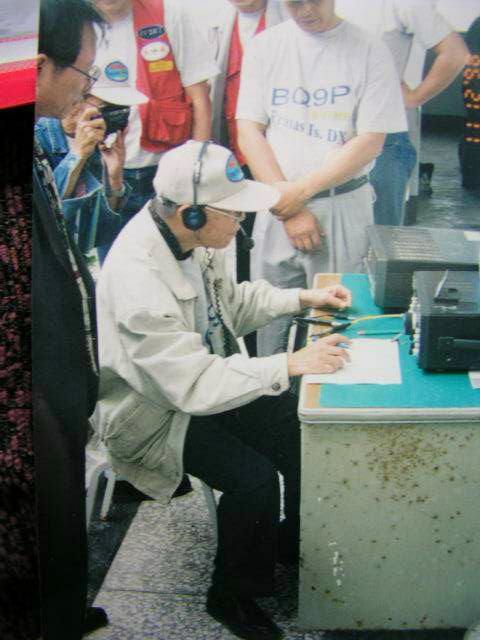

Photo: Wang Jui-te, Taipei Times

When Chen died on Feb. 22, 2006, an American Radio Relay League (ARRL) obituary noted that Chen was “more famous than he knew.” Indeed, Chen told Commonwealth Magazine in 1984 that his favorite part of amateur radio was the people he could connect to.

“Think about it, now there’s at least 70,000 or 80,000 people in the world who know me,” Chen said. “Where else would you have the chance to make so many friends?”

FROM The NORTH POLE TO ANTARCTICA

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Chen got his start in amateur radio when he was a 19 year old in China. He stopped for several years after retreating to Taiwan with the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) in 1949, but in 1955 he rekindled his passion by forming the Chinese Radio Association (中國無線電協進會) with a few friends. He managed to obtain a operating license through the association before the government decided that it was too risky to issue any more.

Chen established BV2A in 1960, drawing quite a stir around the ham world. He tells Commonwealth Magazine that since enthusiasts are drawn to remote and obscure locations, they jumped at the chance to speak to the first and only operator in Taiwan.

By the time Commonwealth Magazine visited Chen’s 5-ping (16.5m2) space, he had connected with people on every continent — including Antarctica and the North Pole. Chen told the magazine that he dutily performed his part in “citizen diplomacy” by explaining to his contacts where Taiwan was located and the difference between the Republic of China (ROC) and the People’s Republic of China.

Photo courtesy of Seattle Municipal Archives

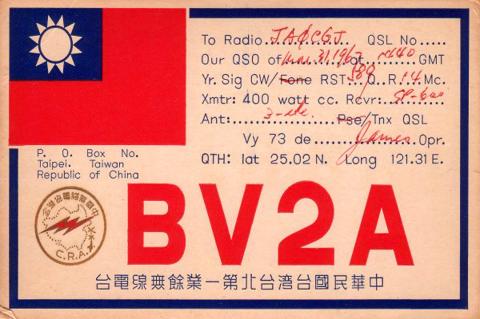

Chen was always excited to send out a signal because he never knew where it would go or who he would get on the other end. After exchanging names and addresses, enthusiasts would mail “QSL cards” to each other. The size of a postcard, this card provides the user’s frequency, address, times for communication and other vital information.

Instead of a personal emblem, Chen station’s QSL identification card, which he had mailed to more than 200,000 users around the world by 1983, displayed an ROC flag. The walls of his cramped space were plastered with QSL cards he had received. A favorite story he liked to tell was when he picked up signals from a station belonging to Palden Thondup Namgyal, the last ruler of the Kingdom of Sikkim in today’s India. Unfortunately, the king did not reciprocate, leading to a missed connection.

His contacts came in handy when he and his wife traveled abroad, as people whom he never met would show up to give them a tour of each city. When they were denied entry into the UK, two British radio enthusiasts showed up to serve as guarantors.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

And people visited Taiwan because of him as well. He told Commonwealth Magazine that he would often receive 50 to 60 foreign visitors per year.

ADVENTURES ON AIR

Chen also took part in international amateur radio competitions. A Taiwan Review article from 1983 sums up his third straight championship in the continuous wave (CW) category. More than 300 amateurs from 100 countries took part, where they sent continuous signals for up to 24 hours in a bid to reach as many stations as they could. Contestants were awarded one point for making a connection in their region, three for an intercontinental connection and five for reaching a station in Brazil, which was that year’s host country.

Chen could only spare eight hours due to his health and job constraints, but he managed to connect with 274 stations in more than 30 countries en route to the trophy.

The government’s decision to start issuing ham licenses again in 1984 was big news to the amateur radio community. A bulletin by the Texas DX Society announced the news with the entry, “BV-Taiwan … not so rare?” where it called Taiwan a “small but very important island” and noted that “in the not so distant future, BV will surely be a regular for all contests.”

Now no longer alone, Chen continued his ham adventures as his association grew and undertook more ambitious endeavors. In 1998, an 84-year-old Chen became the oldest person to set foot on the Pratas Island (Dongsha Island, 東沙島) in the South China Sea, connecting with tens of thousands of enthusiasts using portable equipment.

In 2005, the government recognized Chen as the “Father of Amateur Radio in Taiwan” and presented him with a lifetime achievement award. When he died, fellow enthusiasts posted memorials about him under his ARRL obituary, with a user writing, “It seems as if all the great ones have passed.”

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.

Towering high above Taiwan’s capital city at 508 meters, Taipei 101 dominates the skyline. The earthquake-proof skyscraper of steel and glass has captured the imagination of professional rock climber Alex Honnold for more than a decade. Tomorrow morning, he will climb it in his signature free solo style — without ropes or protective equipment. And Netflix will broadcast it — live. The event’s announcement has drawn both excitement and trepidation, as well as some concerns over the ethical implications of attempting such a high-risk endeavor on live broadcast. Many have questioned Honnold’s desire to continues his free-solo climbs now that he’s a

Lines between cop and criminal get murky in Joe Carnahan’s The Rip, a crime thriller set across one foggy Miami night, starring Matt Damon and Ben Affleck. Damon and Affleck, of course, are so closely associated with Boston — most recently they produced the 2024 heist movie The Instigators there — that a detour to South Florida puts them, a little awkwardly, in an entirely different movie landscape. This is Miami Vice territory or Elmore Leonard Land, not Southie or The Town. In The Rip, they play Miami narcotics officers who come upon a cartel stash house that Lt. Dane Dumars (Damon)

Francis William White, an Englishman who late in the 1860s served as Commissioner of the Imperial Customs Service in Tainan, published the tale of a jaunt he took one winter in 1868: A visit to the interior of south Formosa (1870). White’s journey took him into the mountains, where he mused on the difficult terrain and the ease with which his little group could be ambushed in the crags and dense vegetation. At one point he stays at the house of a local near a stream on the border of indigenous territory: “Their matchlocks, which were kept in excellent order,

As Taiwan’s second most populous city, Taichung looms large in the electoral map. Taiwanese political commentators describe it — along with neighboring Changhua County — as Taiwan’s “swing states” (搖擺州), which is a curious direct borrowing from American election terminology. In the early post-Martial Law era, Taichung was referred to as a “desert of democracy” because while the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) was winning elections in the north and south, Taichung remained staunchly loyal to the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT). That changed over time, but in both Changhua and Taichung, the DPP still suffers from a “one-term curse,” with the