About a year ago, more than a decade after I moved to the area, I stumbled quite by accident across a short hiking trail 6km from my home. The Ganlan Mountain Path (橄欖山登山步道) is just inland of Hutoupi (虎頭埤) in Tainan City’s Sinhua District (新化). Hutoupi is a small reservoir, and notable for being one of very few significant infrastructure projects in Taiwan initiated by the Qing authorities before the Japanese took control of the island in 1895.

The trail doesn’t appear on Google Maps, which perhaps isn’t surprising. The “mountain” is only slightly higher than the surrounding countryside, and a fast walker can get from one end of the path to the other in less than 10 minutes. The toponym means “mountain of olives,” and there’s another Ganlan Mountain about 9km away in Zuojhen District (左鎮).

As well as lots of bamboo, Sinhua’s Ganlan Mountain does have some impressively tall Ceylon Olive (elaeocarpus serratus) trees. The fruit they produce is much larger than that from the European Olive. It’s also less palatable, which is why olives have never been a meaningful element in local diets. The principal attraction here isn’t fruit, however, but military history.

Photo: Steven Crook

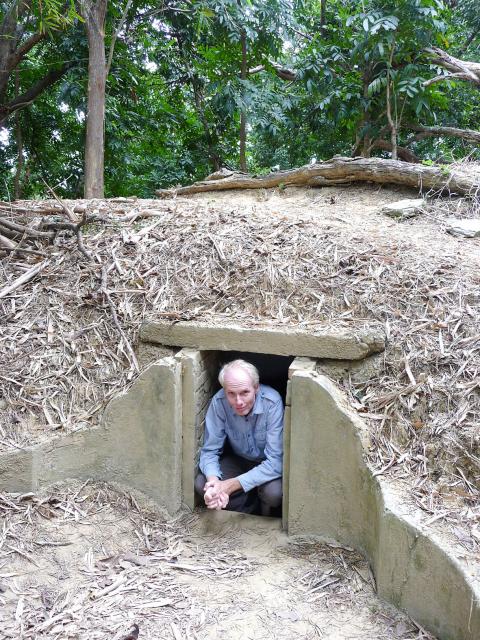

A Chinese-language mapboard at the entrance says the area was used to train soldiers after Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) regime relocated to Taiwan in 1949. It points out seven features of interest, among them ruined buildings; gun emplacements; a tunnel; and an extraordinary “fake grave” (假墓).

The mock tomb does resemble the old graves I often come across in Taiwan’s foothills. However, where you would normally see a tombstone bearing the deceased’s name, there’s an entrance through which an adult can just about squeeze. At a pinch, perhaps five men and their weapons could conceal themselves in the underground chamber — and there’s nothing to stop curious visitors from taking a look inside. It’s not obvious if those hiding within could seal the grave, or if they needed someone on the outside to slide the fake tombstone into position.

The mapboard doesn’t say for what the soldiers were training. To defend Taiwan in the event of a Communist invasion? Or to retake China, as KMT leader Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石) had vowed to do? According to some sources, this training area was intended to prepare Republic of China (ROC) Army units for combat in Vietnam.

Photo: Steven Crook

COLD WAR

One blogger writing in Chinese reports: “Local people say Ganlan Mountain was a heavily-guarded military base from the 1950s onward, created by the army to simulate a communist village in Vietnam. There were mock temples, tombs and houses, all connected underground. There were trenches and tunnels, to teach soldiers the tactics of the Viet Cong.”

Another says that military personnel also learned how to live off the land by foraging for edible plants and fruits (including, presumably, the olives).

Photo: Steven Crook

It’s no secret that Chiang hoped to contribute militarily to the anti-communist struggle in Indochina. KMT officials told Washington they wished to station part of the army in the thick of it so as to gain valuable combat experience. But because they suspected Chiang was planning to use Vietnam as a base from which he could attack the China, the Americans turned down his offer.

Even so, the ROC assisted South Vietnam until its collapse. In 1959, a South Vietnamese military delegation toured Taiwan to learn from their KMT counterparts. The following year, Ngo Dinh Diem — first president of the pro-US Republic of Vietnam — visited Taiwan and asked Taipei to help Saigon establish a political warfare bureau for its armed forces, similar to the system Chiang Ching-kuo (蔣經國) had instituted within the ROC military.

Washington wasn’t convinced as to the value of dedicated political-warfare officers, however, so the first cohort of Chinese Nationalist advisers had to enter South Vietnam under false names and in civilian attire.

Photo: Steven Crook

By 1964, Ngo was dead, the situation in South Vietnam was rapidly worsening and the Americans were more favorably disposed to KMT-style political warfare. With Washington’s blessing — and insistence that it not participate in combat missions, for fear of drawing Beijing into the war — the Republic of China Military Advisory Group, Vietnam (中華民國駐越軍事顧問團) was deployed that October. The group’s 15 members (later increased to 31) were allowed to wear ROC uniforms.

In addition to providing training and advice relating to political warfare, the ROC officers were directed to help “reform” those taken prisoner by South Vietnam, and to gather intelligence which the KMT could apply when endeavoring to reconquer China.

The presence of the team from Taiwan was no secret. On Aug. 15, 1965, the Free China Weekly (an ROC government English-language propaganda publication) reported that the team had won “the high respect” of South Vietnam’s leaders and people, and that the ROC advisers had “taken time out to visit various war fronts… [in such] strategic areas as Khanh Hoa, Da Nang and the Mekong delta. They are often under Viet Cong fire.”

Photo: Steven Crook

Throughout this period, Taipei also provided non-military help in the form of: agricultural equipment, fertilizer, and farming know-how; rice; and surgical teams. Just as thousands of US Department of Defense employees stayed on in South Vietnam after American combat units pulled out after the Paris Peace Accords were signed in 1973, Taiwanese advisers were active until April 18, 1975, less than two weeks before the fall of Saigon.

When exploring Ganlan Mountain and its Cold-War remnants, do take care. The trail is littered with fallen branches, and many of the steps have slid out of position. If you climb into a trench or enter a tunnel, you do so entirely at your own risk.

IF YOU GO

From central Sinhua, take Sinyi Road (信義路) east under Freeway 3. Stay on this road, which is also known as Local Road 172 (南172), for 700m after passing the entrance to Tainan Golf Course (台南高爾夫球場). Where Local Road 172 veers left, take the smaller road going right. You’ll see the Heart of Buddha Temple (心佛寺) on your right. Keep going for another few hundred meters; the starting point of the Ganlan Mountain Path (橄欖山登山步道) is on the right, but there’s no obvious sign, just a set of low bollards to stop cars from parking here.

The primaries for this year’s nine-in-one local elections in November began early in this election cycle, starting last autumn. The local press has been full of tales of intrigue, betrayal, infighting and drama going back to the summer of 2024. This is not widely covered in the English-language press, and the nine-in-one elections are not well understood. The nine-in-one elections refer to the nine levels of local governments that go to the ballot, from the neighborhood and village borough chief level on up to the city mayor and county commissioner level. The main focus is on the 22 special municipality

The People’s Republic of China (PRC) invaded Vietnam in 1979, following a year of increasingly tense relations between the two states. Beijing viewed Vietnam’s close relations with Soviet Russia as a threat. One of the pretexts it used was the alleged mistreatment of the ethnic Chinese in Vietnam. Tension between the ethnic Chinese and governments in Vietnam had been ongoing for decades. The French used to play off the Vietnamese against the Chinese as a divide-and-rule strategy. The Saigon government in 1956 compelled all Vietnam-born Chinese to adopt Vietnamese citizenship. It also banned them from 11 trades they had previously

Hsu Pu-liao (許不了) never lived to see the premiere of his most successful film, The Clown and the Swan (小丑與天鵝, 1985). The movie, which starred Hsu, the “Taiwanese Charlie Chaplin,” outgrossed Jackie Chan’s Heart of Dragon (龍的心), earning NT$9.2 million at the local box office. Forty years after its premiere, the film has become the Taiwan Film and Audiovisual Institute’s (TFAI) 100th restoration. “It is the only one of Hsu’s films whose original negative survived,” says director Kevin Chu (朱延平), one of Taiwan’s most commercially successful

Jan. 12 to Jan. 18 At the start of an Indigenous heritage tour of Beitou District (北投) in Taipei, I was handed a sheet of paper titled Ritual Song for the Various Peoples of Tamsui (淡水各社祭祀歌). The lyrics were in Chinese with no literal meaning, accompanied by romanized pronunciation that sounded closer to Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese) than any Indigenous language. The translation explained that the song offered food and drink to one’s ancestors and wished for a bountiful harvest and deer hunting season. The program moved through sites related to the Ketagalan, a collective term for the