It all started in 2016 with a bronze statue commemorating the tragic day in November 1963 when a giant octopus upended the Staten Island ferry, killing nearly 400 people in New York.

Wait, what — a giant octopus? Artist Joseph Reginella smiles. Yes, you read that right.

Last year, another statue appeared in Battery Park, at the lower tip of Manhattan — a monument to the Wall Street bankers trampled to death in October 1929 when circus impresario P.T. Barnum’s elephants broke into a panicked stampede while crossing the Brooklyn Bridge. Hard to believe? Well, quite. A few months ago, strollers along the water’s edge in New York found a new statue dedicated to the six crew members of a tugboat who were abducted by aliens in July 1977.

Photo: AFP

The three memorials to three made-up tragedies sprung from the vivid imagination of Reginella, a 47-year-old sculptor and jokester who has made an art out of monuments commemorating non-existent victims.

Reginella — who makes his living building models and props for movies, amusement parks and department stores — realizes it’s rather a peculiar hobby. He makes the bronze sculptures in his spare time, in the basement of his Staten Island home.

His 2016 sculpture of the octopus sinking the ferry was such a popular hit that he decided to produce a new monument each year along the same lines — and following the same sophisticated sense of humor.

Photo: AFP

DOCUMENTS LEND CREDIBILITY

Reginella begins by choosing the date of the invented disaster with care — and having it coincide with a real tragedy.

The ferry “sank” on Nov. 22, 1963, the day president John F. Kennedy was assassinated. The elephant stampede took place on Oct. 29, 1929, the day of the massive Wall Street crash. The tugboat crew “vanished” on the night of July 13, 1977, when a huge blackout plunged New York into darkness.

Photo: AFP

The idea is that the enormity of the real events will make people think — maybe — that they somehow missed the other tragedy that he invented.

“That was my vehicle to kind of try to have people believe this,” he said. “And then I took the template — I had such great success with this, it really went crazy — that I continued the tradition.”

Each statue comes with a plaque explaining the event in earnest tones, designed to lend a whiff of authenticity.

The elephant stampede, for example, is described as “one of the most horrific land mammal tragedies in our nation’s history.”

And at a moment in America when everyone goes to Google to verify or look up information, Reginella pushes the joke onto the Internet, conjuring up a panoply of fake documentation, including newspaper articles and online documentaries to bolster the illusion.

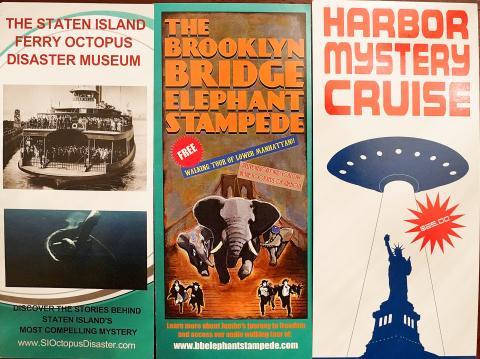

For his latest piece on the tugboat alien abduction, there is even a tourist brochure offering boat tours to the site where the sailors were allegedly kidnapped. A curious observer can type “octopus” and “Staten Island ferry” into YouTube and find a black-and-white documentary featuring archival footage of putative wreckage, along with witnesses and experts talking about the disaster.

Each event has its own Web site with souvenirs on sale, including real t-shirts priced at US$25 each and reproductions of the original model for US$100 a piece.

Several thousand fans of Reginella’s work, who share his quirky sense of humor, have bought a piece of his alternate history, allowing him to finance new projects, which generally take him six to nine months to complete, with the help of his wife and friends.

Despite their size, the statues are easy to assemble and move, and Reginella unveils them in Battery Park on weekends or in his spare time.

NOT ‘FAKE NEWS’

With such a high degree of sophistication, Reginella could pass for a pioneer of the “fake news” that has taken over social media in recent years.

But he rejects the term — a catch phrase closely associated with President Donald Trump and his attacks on the media.

“Mine is much more for fun, it’s not malicious,” he said. “I am more like the carnival barker, showing you the sideshow attraction.”

Despite his growing profile, Reginella remains rather humble about it all, and sees himself as a purveyor of inoffensive “hoaxes” for entertainment purposes.

The artist revels in the amused reactions of passers-by who stop to take selfies with his sculptures, some of whom wonder aloud if the events actually occurred.

Of course, despite the fantastical details of the alleged events, some people actually believe they are true. But usually, that belief is quickly dispelled. If someone persists in their belief, Reginella is the first to regret it.

“Some people just look at it and they’re just like, ‘Huh, who knew?’” he laughed. “And I’m like, ‘Are you kidding me?’” “It did not really anger me, but it really got me thinking. It was kind of a letdown.”

He admits there is “a flip side to it. It’s definitely to show people, ‘Don’t take things at face value, do your due diligence.’”

Reginella remained coy about his next project, and said he may even take a break next year from his usual production of one sculpture a year.

“I really don’t want to say because... it’s like a magician not wanting to reveal his secrets,” he says.

This month the government ordered a one-year block of Xiaohongshu (小紅書) or Rednote, a Chinese social media platform with more than 3 million users in Taiwan. The government pointed to widespread fraud activity on the platform, along with cybersecurity failures. Officials said that they had reached out to the company and asked it to change. However, they received no response. The pro-China parties, the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and Taiwan People’s Party (TPP), immediately swung into action, denouncing the ban as an attack on free speech. This “free speech” claim was then echoed by the People’s Republic of China (PRC),

Exceptions to the rule are sometimes revealing. For a brief few years, there was an emerging ideological split between the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) and Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) that appeared to be pushing the DPP in a direction that would be considered more liberal, and the KMT more conservative. In the previous column, “The KMT-DPP’s bureaucrat-led developmental state” (Dec. 11, page 12), we examined how Taiwan’s democratic system developed, and how both the two main parties largely accepted a similar consensus on how Taiwan should be run domestically and did not split along the left-right lines more familiar in

Many people in Taiwan first learned about universal basic income (UBI) — the idea that the government should provide regular, no-strings-attached payments to each citizen — in 2019. While seeking the Democratic nomination for the 2020 US presidential election, Andrew Yang, a politician of Taiwanese descent, said that, if elected, he’d institute a UBI of US$1,000 per month to “get the economic boot off of people’s throats, allowing them to lift their heads up, breathe, and get excited for the future.” His campaign petered out, but the concept of UBI hasn’t gone away. Throughout the industrialized world, there are fears that

Most heroes are remembered for the battles they fought. Taiwan’s Black Bat Squadron is remembered for flying into Chinese airspace 838 times between 1953 and 1967, and for the 148 men whose sacrifice bought the intelligence that kept Taiwan secure. Two-thirds of the squadron died carrying out missions most people wouldn’t learn about for another 40 years. The squadron lost 15 aircraft and 148 crew members over those 14 years, making it the deadliest unit in Taiwan’s military history by casualty rate. They flew at night, often at low altitudes, straight into some of the most heavily defended airspace in Asia.