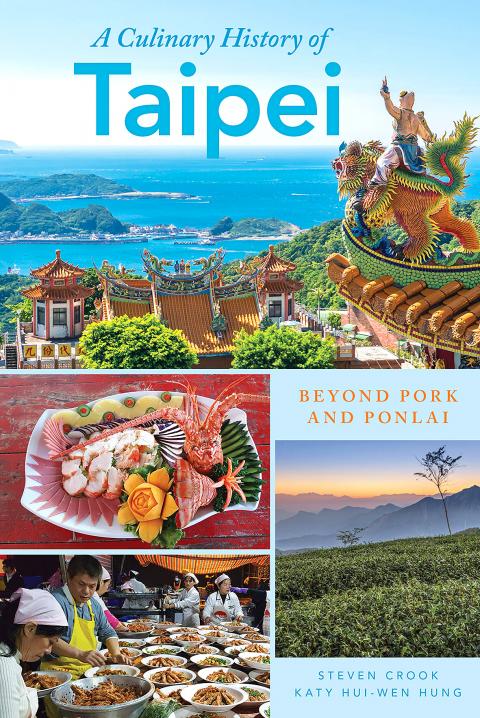

This is probably an unfair gripe to the authors, as A Culinary History of Taipei is part of a semi-academic series of “food biographies” that follow a fixed format, but one cannot help but wish that it contained more photos. While the product is for serious readers and is by no means meant to be leafed through as a pretty coffee-table book, it’s somewhat disappointing when one can almost taste, the food through the vivid descriptions but have few accompanying visuals — and only in black and white.

And while the photos that are featured in the book are all great shots, the print quality leaves them rather dark, seemingly because they were originally toned for color and not black and white. It’s not just about the food: so much of this book is about imagery. This reviewer, having lived in Taiwan for many years, can immediately evoke a mental image when the authors describe the “iconic design” of the Tatung rice cooker, but unfamiliar readers could use some help.

But again, this is a publishing issue and should not detract from Steven Crook and Katy Hui-wen Hung’s (洪惠文) painstakingly researched and immensely detailed ride through Taipei’s foodways, starting from prehistoric foraging to modern culinary superstars and organic eating. (Steven Crook is a Taipei Times contributor who writes the “Highways and Byways” every Friday.) What’s impressive is that with the number of facts and anecdotes packed into every paragraph, the writing remains lively and brisk.

While there’s a lot of information to absorb, it’s still an enjoyable read, especially for those truly interested in learning about Taiwan and wish to delve beyond the usual tired articles, or even worse, listicles that keep bringing up stinky tofu like it’s one of the few things Taiwanese actually eat, along with beef noodles and bubble tea. Most importantly, the authors are longtime residents, familiar with the nation’s gastronomic nuances and minute habits.

There are other books about Taiwan’s food, but A Culinary History of Taipei may be the most thorough, moving beyond the dishes themselves and taking an extended look at the development of everyday gastronomic traditions from the bottom up with the island’s natural resources, moving on to kitchen utensils and condiments and slowly advancing from there. It’s part of the Big City Food Biographies series by Rowman and Littlefield, which, according to the publisher are “not guidebooks” but serve to explain the “urban infrastructure, the natural resources that make each city unique, and most importantly the history, people and neighborhoods.”

The series began from US cities with strong culinary traditions such as New Orleans and Chicago and branched out to major metropolises in other continents such as Paris and Sydney. In comparison, Taipei is a relatively obscure place for the series to make its first stop in Asia, but it’s position in history and myriad influences definitely make it a unique spot to embark.

This “obscurity” is addressed in the foreword, as the authors acknowledge that Taiwanese cuisine is not so established in Western minds as Cantonese or Japanese, with the “island’s distinctiveness … muffled by a history of occupation and exploitation that only ended recently.” Like everything else in Taiwan, it’s impossible to explain all the influences on Taiwanese cuisine without mentioning its politics, which, the authors eloquently conclude a section by stating “it’s only natural that the cuisine’s conventions and boundaries should be as fluid and blurry as the island’s status.”

As a result, presumably, while other books in the series mostly offer a brief timeline before delving into the main subject, this book begins with a four-page introduction on Taiwan’s geography and general history. It’s short and sweet, and just informative enough to not keep the hungry reader waiting.

The word “detailed” has been used several times in this review, but it is not an overstatement, as the entries contain far more information than the average Taiwanese would know about. Each ingredient, dish, industry or tradition is outlined from its scientific background and etymology in the country’s various languages, to its historic development and place in popular culture as well as modern concerns such as health-conscious eating. The last bit perhaps is what makes the book complete — as foodways constantly evolve, there’s no way to talk about a hot pot without observing that the once popular Bullhead Barbecue Sauce has recently fallen out of favor as people try to “reduce their salt and oil intake.”

The icing on the cake is probably the related folk idioms peppered throughout the book, many of them transliterated from Hoklo (also known as Taiwanese) or Hakka.

As the book is academic in nature, most facts are sourced, which provides a glimpse into the research done — historic documents, academic papers, newspaper articles, Web sites such as the Ark of Taste catalog of endangered heritage foods and interviews with both Western and Taiwanese scholars, experts and chefs. While a majority of the written sources are in English, the authors, for example, seek out longtime Japanese residents in Taiwan to discuss the ubiquity of Japanese cuisine in Taiwan, and one section features an extended conversation with prominent Taiwanese “bando” banquet chef Lin Ming-tsan (林明燦), complete with a mouth-watering rundown of the 10 dishes he prepared last year in a collaboration with Le Palais restaurant — the only establishment in Taiwan to boast three Michelin stars.

Each chapter is written in this fashion, and the progression is logical, from a more general look at all the things Taiwanese eat and drink (including snake blood) to food taboos and specific festival and seasonal offerings to food production, markets and restaurants. Aboriginal, Hoklo, Hakka, those who came from China after 1949 and new immigrants from Southeast Asia and other locales are all given the space they deserve, which is not an easy feat to balance.

By the end of the book, which concludes with people who teach, develop and promote Taiwan’s food, few stones are left unturned. A Culinary History of Taipei fittingly concludes in a chat with superstar chef Andre Chiang (江振誠), whose high-end, innovative Taiwanese cuisine at RAW represents new possibilities.

In retrospect, after reading the entire book over just a few days, it should be digested bit by bit due to the sheer amount of information in each chapter as well as the lack of photos. After taking in one section, the reader, if fortunate enough to live in or visit Taiwan, should seek out the items being described, as armed with this new knowledge, even the most seasoned veteran expat will be able to make a new adventure out of it.

Recently the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and its Mini-Me partner in the legislature, the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP), have been arguing that construction of chip fabs in the US by Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC, 台積電) is little more than stripping Taiwan of its assets. For example, KMT Legislative Caucus First Deputy Secretary-General Lin Pei-hsiang (林沛祥) in January said that “This is not ‘reciprocal cooperation’ ... but a substantial hollowing out of our country.” Similarly, former TPP Chair Ko Wen-je (柯文哲) contended it constitutes “selling Taiwan out to the United States.” The two pro-China parties are proposing a bill that

March 9 to March 15 “This land produced no horses,” Qing Dynasty envoy Yu Yung-ho (郁永河) observed when he visited Taiwan in 1697. He didn’t mean that there were no horses at all; it was just difficult to transport them across the sea and raise them in the hot and humid climate. “Although 10,000 soldiers were stationed here, the camps had fewer than 1,000 horses,” Yu added. Starting from the Dutch in the 1600s, each foreign regime brought horses to Taiwan. But they remained rare animals, typically only owned by the government or

Institutions signalling a fresh beginning and new spirit often adopt new slogans, symbols and marketing materials, and the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) is no exception. Cheng Li-wun (鄭麗文), soon after taking office as KMT chair, released a new slogan that plays on the party’s acronym: “Kind Mindfulness Team.” The party recently released a graphic prominently featuring the red, white and blue of the flag with a Chinese slogan “establishing peace, blessings and fortune marching forth” (締造和平,幸福前行). One part of the graphic also features two hands in blue and white grasping olive branches in a stylized shape of Taiwan. Bonus points for

Last month, media outlets including the BBC World Service and Bloomberg reported that China’s greenhouse gas emissions are currently flat or falling, and that the economic giant appears to be on course to comfortably meet Beijing’s stated goal that total emissions will peak no later than 2030. China is by far and away the world’s biggest emitter of greenhouse gases, generating more carbon dioxide than the US and the EU combined. As the BBC pointed out in their Feb. 12 report, “what happens in China literally could change the world’s weather.” Any drop in total emissions is good news, of course. By