A new edition of The Picture of Dorian Gray, featuring handwritten notation from Oscar Wilde, reveals the extent to which the writer grappled with how much homoerotic content he should include in his novel.

It is the first time the original manuscript in Wilde’s own writing has been published and demonstrates how he self-censored some of the most romantic paragraphs. He tones down the more overt references to the homoerotic nature of Basil Hallward’s relationship with Dorian, crossing out his confession that “the world becomes young to me when I hold his hand.”

Yet the manuscript also includes passages — later removed from the novel we know today — that show how Wilde wanted to shock his Victorian readers by openly writing about homosexual feelings. For example, this declaration of love by Basil for Dorian on page 147: “It is quite true that I have worshiped you with far more romance than a man should ever give to a friend. Somehow I have never loved a woman? I quite admit that I adored you madly, extravagantly, absurdly.”

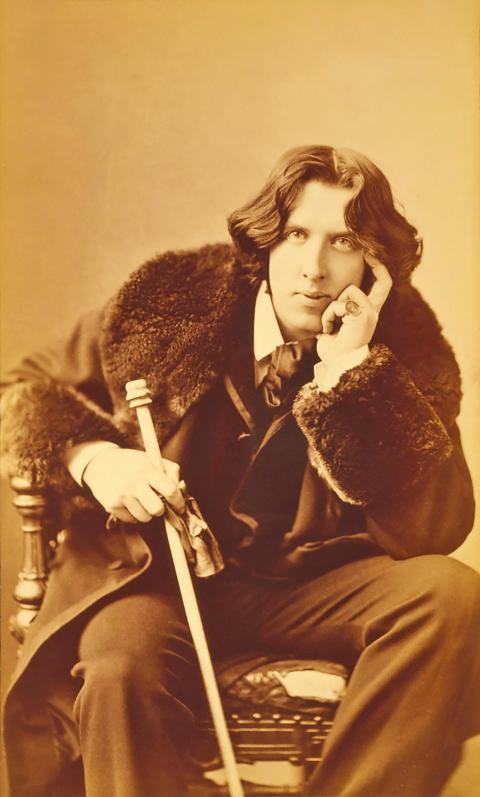

Photo courtesy of wikimedia commons

“The manuscript shows the workings of Wilde’s mind as he was writing it,” said Merlin Holland, the author’s 72-year-old grandson, who has written a foreword to the new edition. “He’d reached a point when he was in danger of becoming respectable and conventional — in 1889 he was married with [two] children, living in slightly bohemian Chelsea. What he’s doing with Dorian Gray is treading a very fine line.”

‘A POSIONOUS BOOK’

In Wilde’s essay The Decay of Lying — published just a few months before he started writing Dorian Gray — he had made a plea for more imagination in literature.

Photo courtesy of pixabay

“I think his whole purpose in writing this book was to break out of the Victorian mould of what Lady Bracknell called the ‘three-volume novel of more than usually revolting sentimentality,’” said Holland. “He does not want, at this juncture of his life, to toe the line and respect social conventions.

His purpose is to shock and tweak the noses of the establishment — but he’s intelligent enough to know that if he goes too far, there is going to be trouble.”

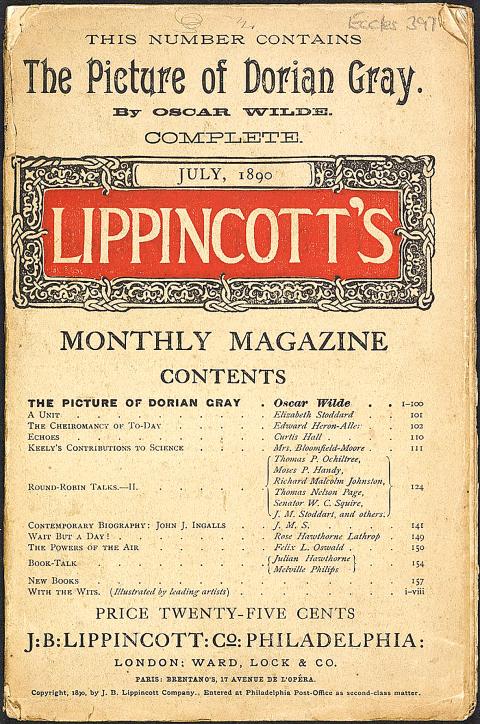

The manuscript was originally published in 1890 by a monthly magazine, Lippincott’s, and was described by critics at the time as “a poisonous book, the atmosphere of which is heavy with the mephitic odors of moral and spiritual putrefaction” and written “for outlawed noblemen and perverted telegraph boys” — a reference to a male brothel where young staff from the General Post Office had been offering out-of-hours “services” to members of the aristocracy.

Following these reviews, the bookseller WH Smith (“ever the self-appointed guardian of British morals,” Holland writes in his foreword) refused to stock Lippincott’s that month. Wilde, under pressure to get the novel published in book format, then toned down the passages the critics had objected to, removing Basil’s declaration of love for Dorian entirely. The novel was published in 1891, and it is Wilde’s self-censored version that is the basis for every popular edition of Dorian Gray today.

LIMITED COPIES

Only 1,000 hand-numbered copies of the manuscript have been printed by publisher SP Books, each costing 200 pounds (about US$260). “It’s a beautiful object — the next best thing to holding the manuscript in your hand,” said Holland, whose father Vyvyan was Wilde’s son.

The family lost all Wilde’s published works when his manuscripts were seized by bailiffs in 1895 — the year Wilde was imprisoned for gross indecency. In court lawyers for the Marquess of Queensberry cross-examined Wilde on the passages in Lippincott’s that he had removed from the novel, citing his story as an “immoral and obscene work.”

“You could say that paragraph on page 147 did terrific harm to his family, which he regretted enormously,” said Holland. “It blighted my father’s early life.”

Vyvyan was eight when Wilde was imprisoned. The writer was never allowed to see either of his sons again and their mother changed their surname. “But people knew,” Holland added.

The manuscript is now owned by The Morgan Library and Museum in New York. Reading a facsimile copy is almost, Holland says, like looking over Wilde’s shoulder as he writes. “Seeing how he constructs his prose is a wonderful thing. It gives you a direct connection to Wilde as a writer.”

In late October of 1873 the government of Japan decided against sending a military expedition to Korea to force that nation to open trade relations. Across the government supporters of the expedition resigned immediately. The spectacle of revolt by disaffected samurai began to loom over Japanese politics. In January of 1874 disaffected samurai attacked a senior minister in Tokyo. A month later, a group of pro-Korea expedition and anti-foreign elements from Saga prefecture in Kyushu revolted, driven in part by high food prices stemming from poor harvests. Their leader, according to Edward Drea’s classic Japan’s Imperial Army, was a samurai

The following three paragraphs are just some of what the local Chinese-language press is reporting on breathlessly and following every twist and turn with the eagerness of a soap opera fan. For many English-language readers, it probably comes across as incomprehensibly opaque, so bear with me briefly dear reader: To the surprise of many, former pop singer and Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) ex-lawmaker Yu Tien (余天) of the Taiwan Normal Country Promotion Association (TNCPA) at the last minute dropped out of the running for committee chair of the DPP’s New Taipei City chapter, paving the way for DPP legislator Su

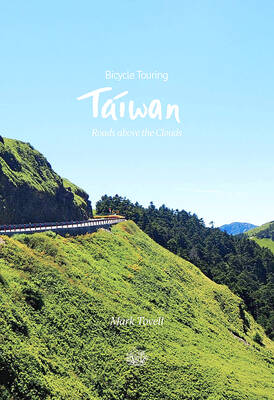

It’s hard to know where to begin with Mark Tovell’s Taiwan: Roads Above the Clouds. Having published a travelogue myself, as well as having contributed to several guidebooks, at first glance Tovell’s book appears to inhabit a middle ground — the kind of hard-to-sell nowheresville publishers detest. Leaf through the pages and you’ll find them suffuse with the purple prose best associated with travel literature: “When the sun is low on a warm, clear morning, and with the heat already rising, we stand at the riverside bike path leading south from Sanxia’s old cobble streets.” Hardly the stuff of your

April 22 to April 28 The true identity of the mastermind behind the Demon Gang (魔鬼黨) was undoubtedly on the minds of countless schoolchildren in late 1958. In the days leading up to the big reveal, more than 10,000 guesses were sent to Ta Hwa Publishing Co (大華文化社) for a chance to win prizes. The smash success of the comic series Great Battle Against the Demon Gang (大戰魔鬼黨) came as a surprise to author Yeh Hung-chia (葉宏甲), who had long given up on his dream after being jailed for 10 months in 1947 over political cartoons. Protagonist