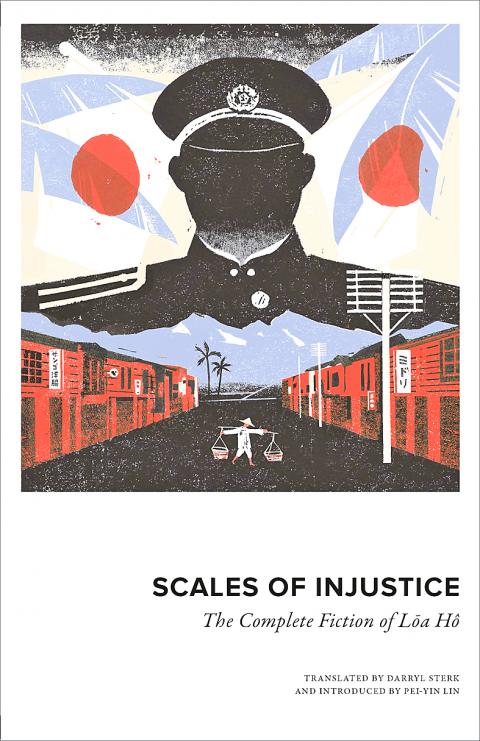

Honford Star is a new independent publisher, based in London and specializing in translations from East Asia. One of their first publications is a complete edition of the short stories of Loa Ho (賴河, 1894-1943), seen by many as the father of Taiwanese literature written in the vernacular.

Loa, also known as Lai He (賴和), wrote during the era of Japanese occupation. Born in Changhua County, he trained and practiced as a doctor, writing fiction only for a period of 12 years in the middle of his life. He was imprisoned twice, albeit for short periods, as a suspected opponent of the Japanese (the second time on the day of the attack on Pearl Harbor). He is consequently seen as both the father of Taiwanese writing in the vernacular and as a chronicler of Taiwan’s colonial era, with a special sympathy for the oppressed.

Darryl Sterk, the distinguished translator, explains in a note that he has felt free to expand the text where he felt a historical explanation was necessary, saying that the author appears to have often disguised his exact meaning in order to get his work past the censor.

Taiwanese Steinbeck

Loa may sound like a Taiwanese Chekhov, being both a doctor and a writer, but the tales themselves read more like Steinbeck. Here are stories of the plight of the ultra-poor, unable to buy presents for their children for the Lunar New Year because of fraudulent inspectors at the market where they work, and of growers of sugar cane defrauded by the company they work for, with its tampered-with scales and last-minute new regulations. In Steinbeck the response of the workers is usually political action, strikes and so forth. Here, the opposition to exploitation is confined to several stories put together in a special section, and is not especially effective.

The notes in this edition are hugely informative. Because, for instance, the subject-matter is so often people’s economic status, money looms large in these stories. So in a key note the translator explains how both the older Chinese terminology — k’uai (silver pieces) and kho (rounds) – and the newer Japanese terminology — yen — were used.

And in a story concerned with the trade in opium, By Chess and Go Boards, characters debate their attitudes to new licensing laws. After an initial attempt to stamp out opium use, we’re told, the Japanese adopted a system of licenses for both addicts and retailers. The term “roasting crows” was used to mean consuming the product because of a similarity of the characters in Chinese. The sale of opium wasn’t made illegal until the end of Japanese rule in 1945.

Some of these stories appear to have been written in response to changes in social conditions, so that a new law, for example, immediately becomes the topic of a Loa tale. Historians will thus value this collection as, in part, a running commentary on life in Taiwan in the 1920s and 1930s, the decades in which most of the stories were written.

Where an author is mentioned at all, Loa uses a pseudonym. Darryl Sterk renders these with some English equivalents — Lazy Cloud (the most common), Doc, Ash and so on. In addition, most of the stories have a date of publication appended, plus the name of the journal where the story first appeared, though for a significant number it’s stated that no date of composition is known.

Sterk says he found it impossible not to warm to Loa and his stories, and I have to agree. They also display a considerable range, moving from a conversation overheard in a train (Going to a Meeting), via a child taken into police custody on the Lunar New Year (A Disappointing New Year) and a cane sugar grower who refuses to complain when he’s denied a bonus (Bumper Crop), to a policemen — “patrolman” — killed by an exploited vegetable seller (A Lever Scale).

Hong Kong University’s Lin Pei-yin (林姵吟), author of Colonial Taiwan: Negotiating Identities and Modernity Through Literature (2017), supplies an informative introduction. In it she points to Loa’s criticisms of traditional Taiwanese attitudes, as well as providing useful insights into the politics of the Taiwan Cultural Association (it divided into left and right factions) during the Japanese era. She compares Loa to China’s Lu Xun (魯迅), though Loa was far less productive, and gives several reasons why he should be better known than he is.

Another topic of interest is Loa’s treatment of medical issues, seeing that he was himself a doctor. The Japanese apparently favored and promoted Western medicine, and considered Chinese herbal remedies ineffective, issues dealt with in Mr Snake and Hope for the Future. Traditional remedies don’t get much sympathy in either story.

Colloquial Style

Darryl Sterk’s style in these translations is pleasantly colloquial. Examples from just one item, The Story of a Class Action (published 1934), include “at the drop of a hat,” “up in arms,” “a class act,” an “opium fix” and “an afternoon snooze.” This story, incidentally, has an unusually optimistic ending and features an idealistic main character, a Mr Grove, though its relationship to Loa’s attitude is less significant than it might be by the story being set, untypically, before the arrival of the Japanese in Taiwan.

A Lever Scale (published 1926) is one of the best items. In it close attention is paid to the multiple ways the police could catch out the poor. “There were your travel regulations, traffic controls, rules of the road, rules concerning food and drink, and rules relating to weights and measures — lift a finger and you might be breaking some rule”. Loa adds a note to this story saying that he witnessed it himself but that it took him some years to dare to set it down. He was finally persuaded by the example of Anatole France.

Honford Star is to be congratulated on this publication. Let’s hope many comparable volumes will soon follow.

May 11 to May 18 The original Taichung Railway Station was long thought to have been completely razed. Opening on May 15, 1905, the one-story wooden structure soon outgrew its purpose and was replaced in 1917 by a grandiose, Western-style station. During construction on the third-generation station in 2017, workers discovered the service pit for the original station’s locomotive depot. A year later, a small wooden building on site was determined by historians to be the first stationmaster’s office, built around 1908. With these findings, the Taichung Railway Station Cultural Park now boasts that it has

The latest Formosa poll released at the end of last month shows confidence in President William Lai (賴清德) plunged 8.1 percent, while satisfaction with the Lai administration fared worse with a drop of 8.5 percent. Those lacking confidence in Lai jumped by 6 percent and dissatisfaction in his administration spiked up 6.7 percent. Confidence in Lai is still strong at 48.6 percent, compared to 43 percent lacking confidence — but this is his worst result overall since he took office. For the first time, dissatisfaction with his administration surpassed satisfaction, 47.3 to 47.1 percent. Though statistically a tie, for most

As Donald Trump’s executive order in March led to the shuttering of Voice of America (VOA) — the global broadcaster whose roots date back to the fight against Nazi propaganda — he quickly attracted support from figures not used to aligning themselves with any US administration. Trump had ordered the US Agency for Global Media, the federal agency that funds VOA and other groups promoting independent journalism overseas, to be “eliminated to the maximum extent consistent with applicable law.” The decision suddenly halted programming in 49 languages to more than 425 million people. In Moscow, Margarita Simonyan, the hardline editor-in-chief of the

Six weeks before I embarked on a research mission in Kyoto, I was sitting alone at a bar counter in Melbourne. Next to me, a woman was bragging loudly to a friend: She, too, was heading to Kyoto, I quickly discerned. Except her trip was in four months. And she’d just pulled an all-nighter booking restaurant reservations. As I snooped on the conversation, I broke out in a sweat, panicking because I’d yet to secure a single table. Then I remembered: Eating well in Japan is absolutely not something to lose sleep over. It’s true that the best-known institutions book up faster