As long as Kristin Chang (張欣明) can remember, her mother has attributed her likes, dislikes, dreams and phobias to past lives. A Buddhist, her mother raised Chang with constant reminders of reincarnation: Chang’s love of cats was a sign that she had once been one; her love of New York City meant that, in a past life, she must have been a New Yorker.

WEIGHED DOWN PAST

Burdened by these legacies, Chang longed for a childhood with Western sensibilities — the individualistic, self-reliant culture she witnessed everywhere in her hometown of Montebello, California. Instead, her Taiwanese immigrant family brought traces of their past to the US.

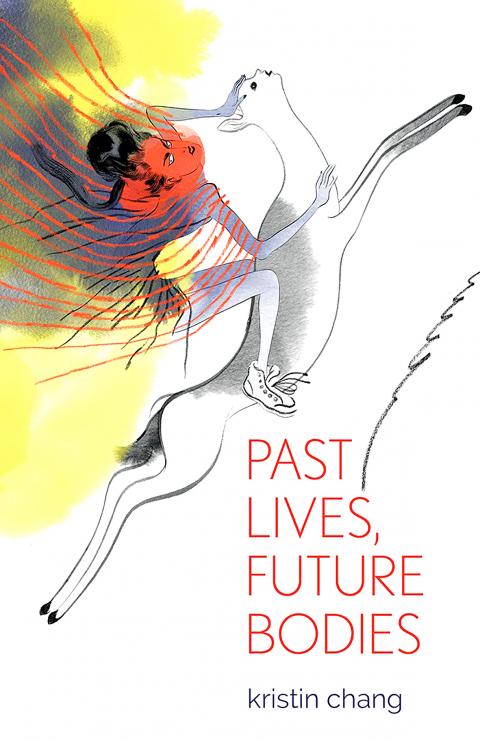

Photo courtesy of Kristin Chang

“I used to think that the very idea of reincarnation stripped me of my agency,” Chang, 19, says. “As if I weren’t a real person, just a collection of past lives; like cats and New Yorkers.”

She fought the label, adopting Christianity and dismissing her mother’s faith.

As an adult, though, Chang feels grounded in her mother’s reincarnation myths, making it a central theme of her debut chapbook, Past Lives, Future Bodies , which will be published in October by Black Lawrence Press. The book seeks to reconcile her origins, both in this life and past ones, and embraces the yet-unknown. In the process, Chang reckons with her family’s experiences.

Chang’s writing did not always serve as such an overt tribute to her roots: as a younger writer, she felt the urge to distance herself from her heritage, in writing as well as everyday life. Feeling removed from her Taiwanese roots, she often aspired to writing like the white American mainstream she read at school.

“The more I wrote like this white edgy hipster, I realized this was another version of colonizing language,” Chang says. “And I felt like an impostor. I realized that I wanted to be a part of another canon of voices, one that I can identify with.”

ASIAN-AMERICAN DIASPORA

For her, poetry has also helped navigate what it means to be part of the Asian-American diaspora, a larger community which transcends her identity as a Taiwanese-American.

“Being Asian-American is an important political choice for me,” she says. Despite the inorganic nature of the label, which has few cultural commonalities, it has become a way for her to connect with other writers who explore the same diaspora.

In centering the Asian-American community, she joins a host of contemporary poets dealing with strikingly similar identity struggles. Acclaimed poets like Ocean Vuong, Cathy Park Hong and Chen Chen have begun to form the canon Chang envisioned when she first began to break away from the white American literary establishment.

For a writer who places Taiwan at the heart of her authorial identity, Chang is surprisingly distant from her relatives’ home country: she has only been to Taiwan once, years ago. As a result, Chang sometimes feels like an stranger in her own heritage, too removed from Taiwanese culture to participate in it.

“There’s a degree of separation that can seem daunting at times,” she says.

Her primary knowledge of Taiwan comes from an amalgamation of family stories and recollections of her only visit. She preserves this patchwork Taiwan carefully in her poems, using her writing to imagine herself in it.

“In Taiwan the rain spits on my skin. / I lose the way to my grandmother’s / house, eat a papaya by the side of the road,” she writes in her Pushcart Prize-winning poem Yilan.

Chang’s persona seems intimately comfortable with Taiwan, despite her alienation from it.

As with any myth, though, her construction of Taiwan is off-color, not quite reaching the truth. In Yilan, Chang describes herself as watching a typhoon from the 65th floor of a Marriott; “smaller buildings lean / like thirst to water” in her invented narrative. But in the real Taipei, there are no 60-floor hotels.

Chang knows that her experience of Taiwan is distanced through a filter of Asian-American identity and diaspora.

“I try not to write from a purely autobiographical place,” she says, pointing to her descriptions of her parents and grandparents peppered throughout her narrative.

As Chang embraced her mother’s reincarnation myths, her poetry similarly serves as a reclamation of identity. Using secondhand stories of a country she has never known herself, she carves out a new Asian-American mythology of her past lives and future bodies.

Jan. 5 to Jan. 11 Of the more than 3,000km of sugar railway that once criss-crossed central and southern Taiwan, just 16.1km remain in operation today. By the time Dafydd Fell began photographing the network in earnest in 1994, it was already well past its heyday. The system had been significantly cut back, leaving behind abandoned stations, rusting rolling stock and crumbling facilities. This reduction continued during the five years of his documentation, adding urgency to his task. As passenger services had already ceased by then, Fell had to wait for the sugarcane harvest season each year, which typically ran from

It’s a good thing that 2025 is over. Yes, I fully expect we will look back on the year with nostalgia, once we have experienced this year and 2027. Traditionally at New Years much discourse is devoted to discussing what happened the previous year. Let’s have a look at what didn’t happen. Many bad things did not happen. The People’s Republic of China (PRC) did not attack Taiwan. We didn’t have a massive, destructive earthquake or drought. We didn’t have a major human pandemic. No widespread unemployment or other destructive social events. Nothing serious was done about Taiwan’s swelling birth rate catastrophe.

Words of the Year are not just interesting, they are telling. They are language and attitude barometers that measure what a country sees as important. The trending vocabulary around AI last year reveals a stark divergence in what each society notices and responds to the technological shift. For the Anglosphere it’s fatigue. For China it’s ambition. For Taiwan, it’s pragmatic vigilance. In Taiwan’s annual “representative character” vote, “recall” (罷) took the top spot with over 15,000 votes, followed closely by “scam” (詐). While “recall” speaks to the island’s partisan deadlock — a year defined by legislative recall campaigns and a public exhausted

In the 2010s, the Communist Party of China (CCP) began cracking down on Christian churches. Media reports said at the time that various versions of Protestant Christianity were likely the fastest growing religions in the People’s Republic of China (PRC). The crackdown was part of a campaign that in turn was part of a larger movement to bring religion under party control. For the Protestant churches, “the government’s aim has been to force all churches into the state-controlled organization,” according to a 2023 article in Christianity Today. That piece was centered on Wang Yi (王怡), the fiery, charismatic pastor of the