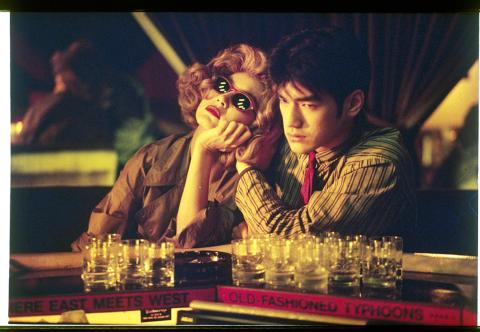

It is the year 1994. A mysterious young woman in a yellow raincoat, shades and blonde wig dashes through the seedy labyrinthine of Chungking Mansions, against the bright lights of Hong Kong’s urban nightscape.

Some people may instantly identify the above scene straight out of Wong Kar-wai’s (王家衛) romantic masterpiece Chungking Express (重慶森林), and the lady onscreen as Taiwanese screen legend Brigitte Lin Ching-hsia (林青霞), in one of her most classic film roles before retirement. Away from the public eye for the last 20 years, the elusive Lin re-entered the limelight at last month’s Hong Kong International Film Festival (HKIFF) and the Far East Film Festival (FEFF) in Udine, Italy.

Both festivals paid tribute to the actress by showing a retrospective of her best works, including Chungking Express and newly-restored versions of Cloud of Romance (我是一片雲, 1977) and Outside the Window (窗外, 1973), courtesy of the Taiwan Film Institute. At FEFF, Lin was also bestowed with the festival’s highest honor, the Golden Mulberry Lifetime Achievement Award.

Photo courtesy of Ricky Modena

Born in 1954, Lin has enjoyed an illustrious filmmaking career over three eras from the 1970s to the 1990s. At 17 years old, she made her breakthrough in Taiwan when she debuted in Outside the Window, which was based on a book by popular romance novelist Chiung Yao (瓊瑤). This was followed with leading roles in a string of hit melodramas adapted from Chiung’s other works, establishing Lin as the new IT girl.

With her youthful complexion and striking beauty, the now 63-year-old superstar doesn’t look a day over 30. As an accidental actress who had been spotted on the streets of Taipei by a talent scout, Lin recalls having to independently navigate her way in a no frills, guerrilla-style filmmaking environment at a time when Taiwanese cinema was just emerging.

“There were no agents, no companies and as actors we had to do everything by ourselves,” she tells the Taipei Times. “I would do my own make-up, prepare my own outfits from home and bring them to set the next day.”

Photo courtesy of Far East Film

FOR THE LOVE OF ACTING

Despite the minimal conditions of the early days, Lin produced a staggering output of 55 films in Taiwan between 1972 and 1979 — even working on six films at one point — that she says was motivated by a sheer love for acting.

“I almost got no sleep, shooting eight hours in one film, followed by eight hours in another and eight hours in a third film. But whenever we were done at the end of the day, I never thought of packing up. I always couldn’t bear to go home.”

Photo courtesy of Far East Film

It was Lin’s foray into the thriving Hong Kong film industry in the 1980s and 90s, however, that would propel her to new heights, eventually cementing her status as an icon of Chinese-language cinema. Moving to the former British colony in 1984 meant a completely different change of pace and scale for the actress, who at that time was still dealing with her budding fame.

“The rhythm in Hong Kong was much quicker, and there was a whole organization that took care of me. When my films were shown there, I became famous overnight,” she says. “A lot of producers [reached out] to me and I didn’t know what to choose, what kind of offer to accept. In some cases, I simply wasn’t allowed to say no.”

Audiences here and in Hong Kong would certainly remember the actress for her onscreen versatility, especially her androgynous roles in wuxia films that challenged the traditional notions of sexuality and femininity of that time. She was patriotic rebel Tsao Wan in Peking Opera Blues (刀馬旦, 1986), masculine alter ego Murong Yang in Ashes of Time (東邪西毒, 1994) and the iconic warrior Dongfang Bubai in Swordsman II (笑傲江湖之東方不敗, 1992).

At the peak of her stardom, Lin was the darling of Hong Kong New Wave directors such as Patrick Tam (譚家明), Tsui Hark (徐克) and Ann Hui (許鞍華), with many scrambling for her to star in their projects. Yet to this day, her most challenging collaborations remain with none other than art house auteur Wong Kar-wai, who directed her in Chungking Express and Ashes of Time.

Working with Wong — who is notorious for not using scripts on set — was akin to entering an “unknown land,” Lin says with a laugh. “With Tsui Hark, I was always fully confident because he made sure that I did a lot of preparation. But with Wong Kar-wai, I never knew what would happen.”

She adds: “On the first day of shooting (Ashes of Time), I remember being so concerned and stressed that I started crying, because I didn’t know what to do. Wong’s approach was to just put me there on set and see what happens.”

COMMITMENT TO HER CRAFT

There’s no doubt how committed Lin has always been to her craft, even going so far as to perform her own stunts when dabbling in contemporary action and martial arts films. She admits to putting her own life in danger on several harrowing occasions, from a near-drowning incident on the set of Swordsman II to passing out mid-air in Jackie Chan’s (成龍) Police Story (新警察故事, 1985).

“Jackie Chan told me I could use a stuntman, but if I shot the scenes myself, I would be remembered forever,” Lin says, describing a particularly dangerous scene where she had to be lifted and thrown onto a table by a man.

“When I was hailed into the air, I fainted because I was too scared. Then the director told me I had to reshoot the scene because I didn’t look into the camera, so nobody could tell it was me.”

Lin may be first and foremost an actress, but she professes to have found an equal love for another vocation: writing. Since retirement, she has published memoirs reminiscing about her experiences in the film industry, as well as late friends Teresa Teng (鄧麗君 ) and Leslie Cheung (張國榮).

“Writing is tiring and difficult, but I can sit at my desk for hours and hours, writing through the night to dawn. I never had any prior writing experience, but I learned that it’s not about using heavy vocabulary, and more about how I can express my sincerity,” she says.

Whether on paper or on screen, it’s clear that Lin’s legacy is set to remain even more timeless, as a new generation of audiences become exposed to her works. On the restoration of her old films, Lin says: “I haven’t filmed for 20 years, but it appears that people are still familiar with me because they can see my films on the Internet.”

“Now we are living in the digital age. I feel very lucky and appreciative that young people now have the opportunity of coming to know the kind of films we shot in the past.”

Taiwan has next to no political engagement in Myanmar, either with the ruling military junta nor the dozens of armed groups who’ve in the last five years taken over around two-thirds of the nation’s territory in a sprawling, patchwork civil war. But early last month, the leader of one relatively minor Burmese revolutionary faction, General Nerdah Bomya, who is also an alleged war criminal, made a low key visit to Taipei, where he met with a member of President William Lai’s (賴清德) staff, a retired Taiwanese military official and several academics. “I feel like Taiwan is a good example of

March 2 to March 8 Gunfire rang out along the shore of the frontline island of Lieyu (烈嶼) on a foggy afternoon on March 7, 1987. By the time it was over, about 20 unarmed Vietnamese refugees — men, women, elderly and children — were dead. They were hastily buried, followed by decades of silence. Months later, opposition politicians and journalists tried to uncover what had happened, but conflicting accounts only deepened the confusion. One version suggested that government troops had mistakenly killed their own operatives attempting to return home from Vietnam. The military maintained that the

“M yeolgong jajangmyeon (anti-communism zhajiangmian, 滅共炸醬麵), let’s all shout together — myeolgong!” a chef at a Chinese restaurant in Dongtan, located about 35km south of Seoul, South Korea, calls out before serving a bowl of Korean-style zhajiangmian —black bean noodles. Diners repeat the phrase before tucking in. This political-themed restaurant, named Myeolgong Banjeom (滅共飯館, “anti-communism restaurant”), is operated by a single person and does not take reservations; therefore long queues form regularly outside, and most customers appear sympathetic to its political theme. Photos of conservative public figures hang on the walls, alongside political slogans and poems written in Chinese characters; South

Taipei Mayor Chiang Wan-an (蔣萬安) announced last week a city policy to get businesses to reduce working hours to seven hours per day for employees with children 12 and under at home. The city promised to subsidize 80 percent of the employees’ wage loss. Taipei can do this, since the Celestial Dragon Kingdom (天龍國), as it is sardonically known to the denizens of Taiwan’s less fortunate regions, has an outsize grip on the government budget. Like most subsidies, this will likely have little effect on Taiwan’s catastrophic birth rates, though it may be a relief to the shrinking number of