For most of their long history of habitation, the group of islands collectively known as Matsu (馬祖, just off Chinese-controlled Fujian Province) have remained a quiet, largely forgotten backwater. For a brief but turbulent period in the 1950s, Matsu (along with Kinmen) became a potent worldwide symbol of the bitter fight against communism, but even before the cold war finally wound down in the late 1980s, Matsu was forgotten once more, and remained an unknown quantity to outsiders until after the islands were opened to civilians in the mid-1990s.

The fact that Matsu opened to tourism only about 20 years ago is, of course, one of its great attractions for the curious traveler, together with the hilly, richly scenic landscapes, impressive coastal scenery, traditional buildings that blend harmoniously with the landscape and friendly Hoklo-speaking (also known as Taiwanese) islanders.

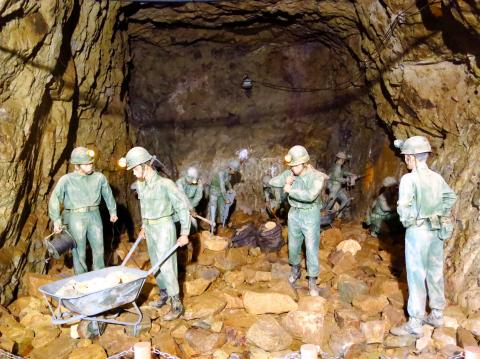

Photo by Richard Saunders

The largest island in the Matsu group, Nangan (南竿), has the best transport connections with Taiwan, with planes from Taipei and a fun overnight ferry service from Keelung. Arriving from either city is quite a surprise, as the island seems to exist in a time-warp, lagging 20 or 30 years behind the rest of the country. In reality, Nangan is by some way the most developed and most densely populated island (take the short ferry ride to neighboring Beigan (北竿), and you’ll immediately feel the difference), but with the widest range of natural, cultural and military sights of the seven accessible Matsu islands, Nangan deserves at least a day of your time.

Most visitors arrive by airplane at the airport on the east coast of the island, close to the island’s main village, Shanlung (山隴), which sprawls downhill from a distillery to the coast and an attractive small bay. Beside the road on the way from the airport to the village is Tunnel 88 (八八坑道), originally cut for military use, but now used by Matsu Liquor Factory to age its kaoliang spirit.

Head west from the airport along the main road crossing the hilly spine of the island, rather grandly known as Central Boulevard (中央大道), and follow the signs to Nangan’s biggest tourist attraction, Beihai Tunnel (北海坑道). This is the largest and most impressive of the three flooded subterranean tunnels in Matsu, and a compulsory stop for all visitors, especially since the other two — on Beigan and Dongyin (東引) islands — are now both closed to visitors.

This series of four crisscrossing tunnels took four battalions nearly three-and-a-half years to dig, are about 18m high, 10m wide and 700m long; the water is eight meters deep at high tide. A raised walkway goes right round the outside edge of the four tunnels (a 20-minute stroll), but a more fun way to explore them is by canoe, which can be rented (NT$300 per person for thirty minutes) from a booth at the tunnel’s entrance.

Nearby is the entrance to Dahan Stronghold (大漢據點), a network of (dry) tunnels emerging as gun turrets in the cliffs that command wonderful views over the ocean. Unfortunately they’re much less atmospheric these days, since some bright spark thought fit to supplement the original dim lighting inside with disco-style light strings that now run the length of each tunnel.

West of Beihai Tunnel the coast road narrows and begins to round the island’s southwest, one of the most secluded and scenic areas of Nangan. On the left in a few hundred meters a small parking place beside the road marks the start of the path down the cliffs to the Iron Fort (鐵堡), one of Nangan’s smaller military relics, but also one of the finest, mainly because of its remarkably scenic setting. Most of the fort is burrowed into the rock, and a long passageway connects a kitchen, sleeping quarters, a small shrine dedicated to Sun Yat-sen (孫逸仙) and several tanks for storing fresh drinking water. The unit had its own pet dog, which curiously held the rank of officer, and had his own kennel up on top of the rock.

Continuing along the coast past pretty Jinsha village (津沙), there’s a succession of lovely views over the ocean all the way to Magang (馬港), once the main gateway to Matsu for ships from Taiwan. All ships now land at Fuao Harbor (福澳港) on the north coast of the island instead, and the village has declined in importance; the main reason to linger is to visit Magang Matsu Temple (馬港天后宮), revered as the tomb of the Goddess of Fishermen.

Locals believe that the body of Lin Mu-niang (林默娘), the Fujianese girl who became Matsu after her death, was washed up on the beach here. The tomb lies beneath the floor, under a large plate of glass in front of the altar. This corner of the island is dominated by the huge, gleaming white statue of Matsu, which can be seen from miles away. The great statue, built in 2009, was trumpeted as the tallest statue of Matsu in the world, at 28m tall.

Nangan’s northern coast is blighted a bit by the island’s power station, and by Fuao Harbor, the main hub for sea transport to and around the Matsu islands. If you take the overnight ferry to Matsu from Keelung, you’ll arrive here just after dawn, to be greeted by a large statue of Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石), and by one of Nangan island’s most famous sights, the huge Always on the Alert wall (福山照壁). This conspicuous white rectangular building is inscribed with the Chinese characters for “Sleeping on Spears, Awaiting the Dawn,” a pointed reminder that Matsu was once a far less soporific place to live than today.

Richard Saunders is a classical pianist and writer who has lived in Taiwan since 1993. He’s the founder of a local hiking group, Taipei Hikers, and is the author of six books about Taiwan, including Taiwan 101 and Taipei Escapes. Visit his Web site at www.taiwanoffthebeatentrack.com.

Oct. 27 to Nov. 2 Over a breakfast of soymilk and fried dough costing less than NT$400, seven officials and engineers agreed on a NT$400 million plan — unaware that it would mark the beginning of Taiwan’s semiconductor empire. It was a cold February morning in 1974. Gathered at the unassuming shop were Economics minister Sun Yun-hsuan (孫運璿), director-general of Transportation and Communications Kao Yu-shu (高玉樹), Industrial Technology Research Institute (ITRI) president Wang Chao-chen (王兆振), Telecommunications Laboratories director Kang Pao-huang (康寶煌), Executive Yuan secretary-general Fei Hua (費驊), director-general of Telecommunications Fang Hsien-chi (方賢齊) and Radio Corporation of America (RCA) Laboratories director Pan

President William Lai (賴清德) has championed Taiwan as an “AI Island” — an artificial intelligence (AI) hub powering the global tech economy. But without major shifts in talent, funding and strategic direction, this vision risks becoming a static fortress: indispensable, yet immobile and vulnerable. It’s time to reframe Taiwan’s ambition. Time to move from a resource-rich AI island to an AI Armada. Why change metaphors? Because choosing the right metaphor shapes both understanding and strategy. The “AI Island” frames our national ambition as a static fortress that, while valuable, is still vulnerable and reactive. Shifting our metaphor to an “AI Armada”

When Taiwan was battered by storms this summer, the only crumb of comfort I could take was knowing that some advice I’d drafted several weeks earlier had been correct. Regarding the Southern Cross-Island Highway (南橫公路), a spectacular high-elevation route connecting Taiwan’s southwest with the country’s southeast, I’d written: “The precarious existence of this road cannot be overstated; those hoping to drive or ride all the way across should have a backup plan.” As this article was going to press, the middle section of the highway, between Meishankou (梅山口) in Kaohsiung and Siangyang (向陽) in Taitung County, was still closed to outsiders

The older you get, and the more obsessed with your health, the more it feels as if life comes down to numbers: how many more years you can expect; your lean body mass; your percentage of visceral fat; how dense your bones are; how many kilos you can squat; how long you can deadhang; how often you still do it; your levels of LDL and HDL cholesterol; your resting heart rate; your overnight blood oxygen level; how quickly you can run; how many steps you do in a day; how many hours you sleep; how fast you are shrinking; how