July 24 to July 30

Public resentment exploded when the conscription order came down in February 1946. The last time Taiwanese faced formal conscription was during World War II, when the Japanese colonial government drafted more than 20,000 men in 1945. They formally enlisted in the Imperial Japanese Army in January, just to catch the tail end of the war.

Already unhappy with the lack of discipline of the 30,000 Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) troops in Taiwan, the people refused to accept governor-general Chen Yi’s (陳儀) plan to send their young men to fight the Communists in China, writes Chen Shih-chang (陳世昌) in 70 Years After the War: A History of Taiwan (戰後70年台灣史).

Photo: Han Cheung, Taipei Times

“The argument was that forced conscription was illegal because China and Japan hadn’t signed a treaty yet,” Chen Shih-chang writes, adding that the people told Chen Yi they would protect their homeland while the 30,000 KMT troops headed to China. Chen Yi scrapped the plan.

FIRST CONSCRIPTS

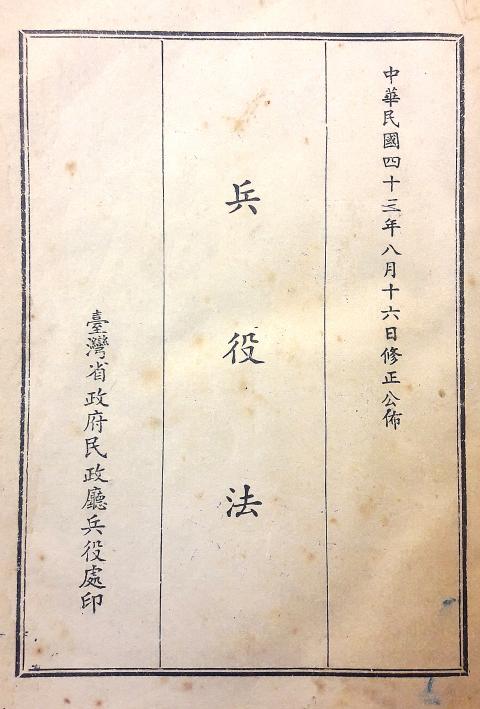

Times were different by the time the second order was issued on July 25, 1951. The KMT had lost China to the Communists and completely retreated to Taiwan, where they set up an authoritarian regime under martial law.

Photos: Han Cheung, Taipei Times

There was no refusing this time. The plan was to draft 14,000 soldiers and 1,000 drivers, writes historian and journalist Hsu Tsung-mao (徐宗懋) in 20th Century Taiwan: Retrocession (20世紀台灣:光復篇), but only about 12,000 reported for duty.

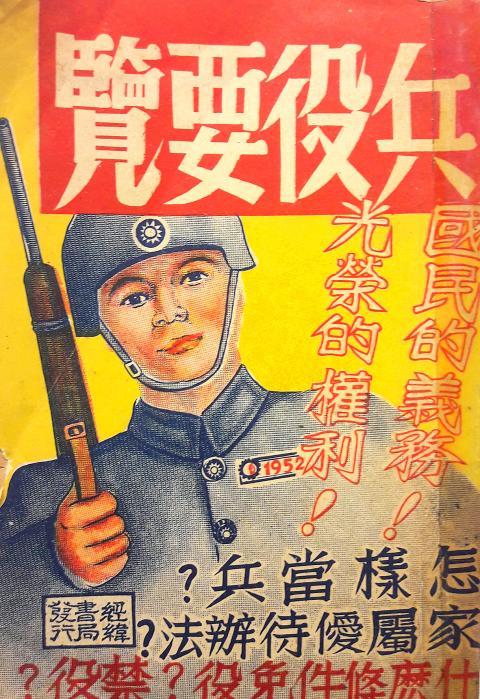

Of course, the official rhetoric back then states that the government was doing the people a service.

An outline for conscription policy published in 1949 states: “Since 1945, the central government has exempted all Taiwanese from conscription out of sympathy for the 50 years of oppression they’ve suffered under the Japanese. But most knowledgeable people know that military service is the duty of all citizens. The people have expressed hope that the government implement conscription soon so that local young men can channel their patriotic passion.”

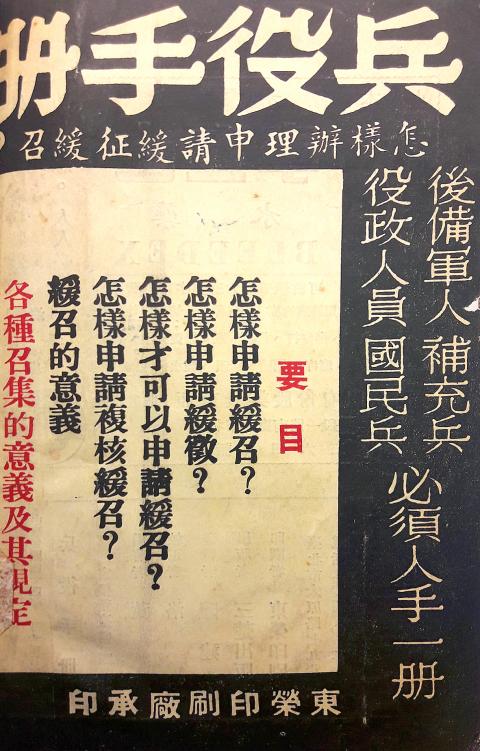

Photo: Han Cheung, Taipei Times

Modern sources tell a different story. A Public Television Service News Network (公視新聞議題中心) article states that the KMT sought to reduce their sky-high defense budget by encouraging professional soldiers to retire and replace them with conscripts.

The state-run Central Daily News (中央日報) ran several editorials warning Taiwanese of the horrors of Communism and why they should fight for the KMT.

“Perhaps there are still people in Taiwan who do not feel as much hatred for the enemy because they have not witnessed the brutality of the Communists, who have caused bloodbaths and mass enslavement in China,” the editorial states. “We need to sincerely inform them that millions in China once felt the same way … they didn’t believe in how venomous the Communists were until it was too late. The only way to avoid being attacked by poisonous snakes and ferocious beasts is to unite and kill them with our weapons. And the only way to save Taiwan from being soaked in blood and ravaged is to join the army, take up a rifle and join the decisive battle!”

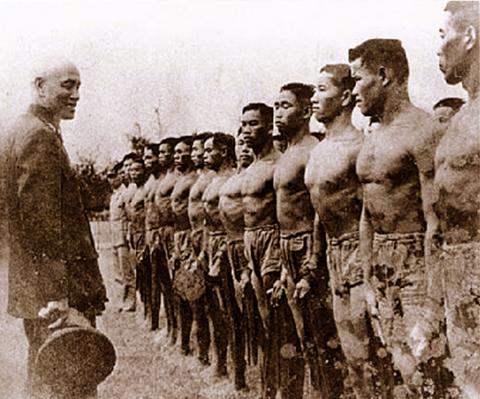

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

After the order was issued, then-Taipei Mayor Wu San-lien (吳三連) announced that “our counterattack [against the Communists] will succeed, and therefore the future of Taiwanese youth will be in China. For the sake of their future, it is imperative for Taiwanese youth to join the fight.”

A SHARED EXPERIENCE

Hsu writes that the conscripts were to report to the camps on Aug. 12, with each locality holding festive farewell parties. In Tainan, the conscripts participated in a parade with professional soldiers as the crowd lit off firecrackers, following the troops until they got on the train. Yilan’s barber shops, public baths and movie theaters did not charge conscripts on that day.

The first night at camp, the conscripts learned several anti-communists songs prescribed by the government, including one personally rewritten and arranged by no other than former President Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石).

From then on, military service became a shared experience for most males in Taiwan, unless they were either exempt or found a way to avoid service. In 1959, the criteria for conscription was broadened due to a shortage of troops. That same year, the practice began of having all males spend time at Chenggong Ling (成功嶺) training camp before they reported to college.

Chiang valued this training camp, often speaking at commencement and graduation ceremonies and delivering speeches to the students to make sure they had the “correct” attitude towards the country’s goals. More than 1.3 million Taiwanese went through this experience before it was abolished in 2000.

By 1974, the Executive Yuan announced that the number of men eligible for military service had far exceeded the needs of the military. Restrictions and requirements were continuously relaxed over the decades until the government announced that it would abolish the draft in favor of an all-volunteer army.

The date has been pushed back several times, the latest news coming in December when the Ministry of Defense announced that this year’s conscripts will be the nation’s final class.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.

Towering high above Taiwan’s capital city at 508 meters, Taipei 101 dominates the skyline. The earthquake-proof skyscraper of steel and glass has captured the imagination of professional rock climber Alex Honnold for more than a decade. Tomorrow morning, he will climb it in his signature free solo style — without ropes or protective equipment. And Netflix will broadcast it — live. The event’s announcement has drawn both excitement and trepidation, as well as some concerns over the ethical implications of attempting such a high-risk endeavor on live broadcast. Many have questioned Honnold’s desire to continues his free-solo climbs now that he’s a

As Taiwan’s second most populous city, Taichung looms large in the electoral map. Taiwanese political commentators describe it — along with neighboring Changhua County — as Taiwan’s “swing states” (搖擺州), which is a curious direct borrowing from American election terminology. In the early post-Martial Law era, Taichung was referred to as a “desert of democracy” because while the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) was winning elections in the north and south, Taichung remained staunchly loyal to the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT). That changed over time, but in both Changhua and Taichung, the DPP still suffers from a “one-term curse,” with the

Lines between cop and criminal get murky in Joe Carnahan’s The Rip, a crime thriller set across one foggy Miami night, starring Matt Damon and Ben Affleck. Damon and Affleck, of course, are so closely associated with Boston — most recently they produced the 2024 heist movie The Instigators there — that a detour to South Florida puts them, a little awkwardly, in an entirely different movie landscape. This is Miami Vice territory or Elmore Leonard Land, not Southie or The Town. In The Rip, they play Miami narcotics officers who come upon a cartel stash house that Lt. Dane Dumars (Damon)

Today Taiwanese accept as legitimate government control of many aspects of land use. That legitimacy hides in plain sight the way the system of authoritarian land grabs that favored big firms in the developmentalist era has given way to a government land grab system that favors big developers in the modern democratic era. Articles 142 and 143 of the Republic of China (ROC) Constitution form the basis of that control. They incorporate the thinking of Sun Yat-sen (孫逸仙) in considering the problems of land in China. Article 143 states: “All land within the territory of the Republic of China shall