Feb. 20 to Feb. 26

About 500 Tao Aborigines from Orchid Island marched toward the southeastern tip of their homeland on the morning of Feb. 20, 1991, raising placards and announcing their desire to rid the island of “evil spirits” — nuclear waste.

This was the third Feb. 20 protest on the island since 1988. The island’s inhabitants say that the waste storage facility was built without their permission and poses a serious threat to their health and the environment.

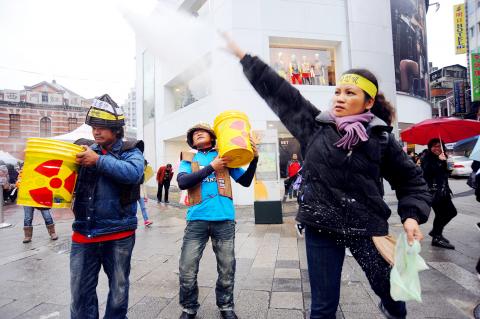

Photo: Chang Tsun-wei, Taipei Times

“This land has a soul, which has protected our tribe. Now, nuclear waste is poisoning it. If we don’t fight back, the damaged land will in turn hurt us because we did not fulfill our responsibility to protect it … Although we choose to protest peacefully, we wear full warrior costume to show our determination to keep fighting,” said protester Syaman Jyavitong.

According to an Orchid Island Biweekly (蘭嶼雙週刊) report, one elderly islander cried during the first protest. “If they keep saying it is so safe, why don’t we each take a barrel and keep it in our houses? Why do we need a storage facility?”

Indeed, when the facility was first built, state-run Taipower Power Co (Taipower, 台電) and government officials repeatedly assured the islanders that the waste was harmless. Orchid Island writer Syaman Rapongan recalls that he was told that “it was safer than hugging two gas barrels while sleeping.”

Photo: Chang Jui-chen, Taipei Times

The Atomic Energy Council launched several “educational” initiatives and set up a nuclear energy exhibition in Taitung to further convince the islanders, but they did not appear swayed.

In response to his people’s plight, Syaman Rapongan penned this poem: “Wild savages, your breakfast is served. Cobalt-60 for the men, cesium-137 for the women. As for the children, their breakfast is extinction.”

KEPT IN THE DARK

Photo: Lo Pei-Der, Taipei Times

How did the facility come about? In August 1971, the Atomic Energy Council met with Taipower and other institutions to discuss what to do with the waste produced at what would be Taiwan’s first nuclear power plant, approved by the government the previous year.

According to a study, The Mobilization of Orchid Island’s Anti-nuclear Movement (蘭嶼反核廢場運動的動員過程分析), by Wang Chun-hsiu (王俊秀), the best option was to dump it in the ocean — but given Taiwan’s declining international standing, they did not want to upset their neighbors. The next best option was to store it on an island.

The committee looked at 14 candidates — some were too small, some didn’t have harbors, some were too developed and some too close to the mainland — finally deciding on Orchid Island.

“The committee considered safety and economic factors, but not public opinion,” Wang writes. “They never informed the Tao people of their plan, and only started communicating with locals under public pressure.”

The committee did consider eventually dumping the waste into the ocean, but that plan was made invalid with the 1975 enforcement of the London Convention on the Prevention of Marine Pollution by Dumping of Wastes and Other Matter.

Wang writes that the Tao people were kept in the dark for almost a decade, finally finding out through media reports in 1982. Wu Jui-lan (吳瑞蘭) writes in A Study of Public Participation in Policymaking (政策的制定與民眾參與之研究) that when construction started, nobody was clear on what was being built — some said a fish cannery, others a military port — but none would have guessed a nuclear waste facility.

RESISTANCE

The first 10,008 barrels of waste arrived on Orchid Island in 1982. The first time the Tao people publicly expressed their displeasure was in 1987, when a group of young men tried to stop the Atomic Energy Council from giving a tour of the facility.

The official resistance began on Feb. 20, 1988 when 200 islanders staged the first “Chasing Away Evil Spirits” protest, and two months later the Orchid Island Youth Friendship Association (蘭嶼青年聯誼會) sent 100 members to support the anti-nuclear protests in front of the Taipower Building in Taipei.

Wang writes that since most Tao people did not understand what nuclear waste was, the young protesters dubbed the facility an anito, or evil spirit, to show other islanders the graveness of the situation.

“When they hold ceremonies to get rid of evil spirits, they must channel their greatest anger,” he writes. “The goal was to show how truly terrifying the facility was.”

In 1996, angry islanders successfully stopped a ship carrying 168 barrels from docking. No more ships would come after that, but almost 100,000 barrels remain on the island.

Protests continued and the issue heated up again when Taipower’s contract for the land expired on Dec. 31, 2011, leading to another Feb. 20 protest in 2012.

Today, the waste is still on the island, and the issue is slowly making headway. Just last week, the Ministry of Economic Affairs announced that it hopes to finalize its decision on a new site this year. Meanwhile, the Tao people continue to wait.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.

Towering high above Taiwan’s capital city at 508 meters, Taipei 101 dominates the skyline. The earthquake-proof skyscraper of steel and glass has captured the imagination of professional rock climber Alex Honnold for more than a decade. Tomorrow morning, he will climb it in his signature free solo style — without ropes or protective equipment. And Netflix will broadcast it — live. The event’s announcement has drawn both excitement and trepidation, as well as some concerns over the ethical implications of attempting such a high-risk endeavor on live broadcast. Many have questioned Honnold’s desire to continues his free-solo climbs now that he’s a

As Taiwan’s second most populous city, Taichung looms large in the electoral map. Taiwanese political commentators describe it — along with neighboring Changhua County — as Taiwan’s “swing states” (搖擺州), which is a curious direct borrowing from American election terminology. In the early post-Martial Law era, Taichung was referred to as a “desert of democracy” because while the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) was winning elections in the north and south, Taichung remained staunchly loyal to the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT). That changed over time, but in both Changhua and Taichung, the DPP still suffers from a “one-term curse,” with the

Jan. 26 to Feb. 1 Nearly 90 years after it was last recorded, the Basay language was taught in a classroom for the first time in September last year. Over the following three months, students learned its sounds along with the customs and folktales of the Ketagalan people, who once spoke it across northern Taiwan. Although each Ketagalan settlement had its own language, Basay functioned as a common trade language. By the late 19th century, it had largely fallen out of daily use as speakers shifted to Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese), surviving only in fragments remembered by the elderly. In

Lines between cop and criminal get murky in Joe Carnahan’s The Rip, a crime thriller set across one foggy Miami night, starring Matt Damon and Ben Affleck. Damon and Affleck, of course, are so closely associated with Boston — most recently they produced the 2024 heist movie The Instigators there — that a detour to South Florida puts them, a little awkwardly, in an entirely different movie landscape. This is Miami Vice territory or Elmore Leonard Land, not Southie or The Town. In The Rip, they play Miami narcotics officers who come upon a cartel stash house that Lt. Dane Dumars (Damon)